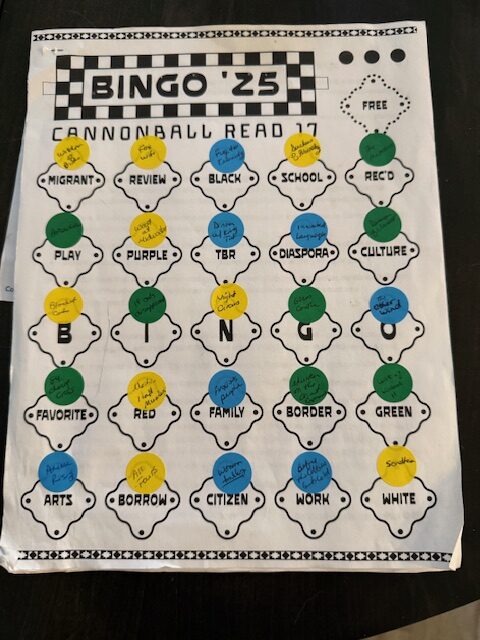

CBR 17 BINGO: Migrant, because many bird species migrate. Quadruple Bingo and Board Blackout!

CBR 17 BINGO: Migrant, because many bird species migrate. Quadruple Bingo and Board Blackout!

Across: Migrant, Review, Black, School, Rec’d

Down: Migrant, Play, “B“, Favorite, Arts

Diagonal: Migrant, Purple, “N“, Border, White

Four corners and the center: Migrant, Rec’d, White, Arts, “N”

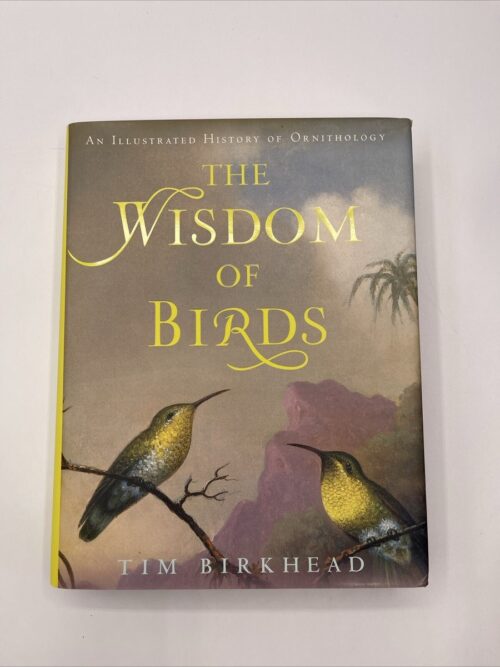

The title of Tim Birkhead’s The Wisdom of Birds is misleading if you fail to read the subtitle, An Illustrated History of Ornithology, which sums up the book nicely. One might wonder why the author didn’t just go with a more precise title, except that it becomes clear in the preface that it’s an homage to the 1691 publication The Wisdom of God by John Ray. Ray was a 17th century naturalist whom Birkhead credits with being the most influential ornithologist of all time. This bold claim surprises even many of Birkhead’s fellow naturalists, but he argues that Ray “transformed the way people viewed the natural world.” Ray’s Wisdom “launched the field study of birds–what we would now call the ecology of birds in their natural environment.” Prior to this, the study of birds was theoretical, based on untested hypotheses and, at best, anecdotal evidence.

While tracing the history of ornithology, Birkhead reveals fascinating details of bird behavior, so this isn’t a dry history as you might expect. It mixes interesting facets of bird life, ranging from migration to intelligence, from bird song to bird sex, with explanations of how ornithologists came to conclusions about these behaviors. Some of the most interesting tidbits in this book come from relating the stubbornness of early scientists–some were so reluctant to give up their old beliefs in the face of new evidence that it wasn’t until the 19th century that the last had been written about the (pretty ridiculous) belief that swallows hibernated in mud over the winter. I also enjoyed reading about how dismissive scientists initially were toward people whom they considered merely hobbyists. According to these guys (whom I guess were easily triggered), if you weren’t in a lab, you weren’t doing science. Today, “citizen science” forms the backbone of the largest bird database in the world. So, there, you stuffy old scientists!

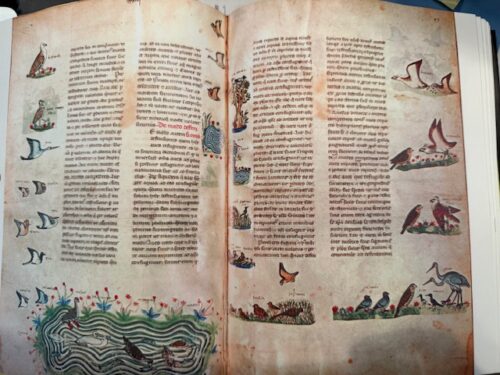

This book is very readable, though if you’re not already a bird enthusiast, I’m not sure this is the one that will win you over (for that, I might recommend Jennifer Ackerman’s The Genius of Birds). What really delights me about this book, however, are the illustrations. Birkhead includes many charming historical prints to highlight his pages. I’m kind of a sucker for old bird prints, and this book contains some beauties, including a gorgeous image from Frederick II’s Art of Falconry (written in the 1240s):

My one caveat is this book is very Euro-focused. There are a few mentions of Australia and the Americas, but other than that, one would suspect that the entire history of ornithology happened in Western Europe. This may be reflective of our written historical record, but I wanted to share that insight to save potential readers from disappointment if they were looking for representation from Asia or Africa.

I enjoyed this book very much, but then I usually do enjoy reading about birds! And with that, I’m wrapping up BINGO for the Birds for 2025.