The genome has been mapped. The systems studied. Everything is known. Just like theworld, they tell themselves. The mysteries have all been solved. There is nothing that could possibly lurk beyond what humans can apprehend. They are wrong. When a virus slips its way into a body, sometimes that body reacts in unexpected ways. It marshals all its defenses and attacks; after all, the virus does not mean well—and then, sometimes, even when the intruder is gone, it keeps attacking. It doesn’t even remember why. It doesn’t make any sense. But that doesn’t mean it isn’t true.

And sometimes, something slips into an abandoned house, something not quite knowable, something that does not belong there. The house sees it and marshals its defenses. It was built to be a home for a family—but this, this is an intruder and it does not mean well. So it reacts in the only way it can think of. Maybe it doesn’t make sense. But that doesn’t mean it isn’t true.

In July, for Disability Pride Month, I decided I was going to focus on reading books about disability or by disabled authors. This was an amazing idea, considering I have a huge, curated list of books specifically about/by disabled authors that I have been compiling for over twenty-five years now, and I’m about a billion and a half books behind in actually reading them and knowing if they’re worth recommending or not. This was also an awful & horrific idea because I immediately read six incredibly good books about disability/chronic illness that triggered my medical PTSD so bad that I had to stop reading anything but cozy fanfic for the next three months. It happens!

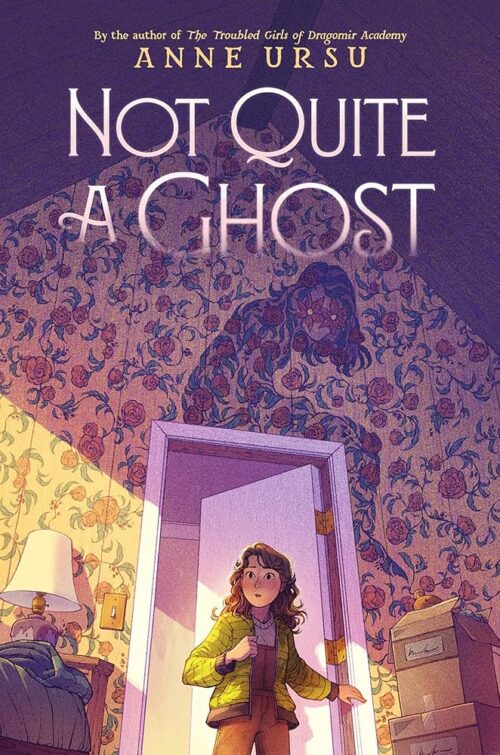

The book that was most triggering, because it was so spectacularly good at mirroring my own experience of coming down with a chronic post-viral disease, following a routine case of mononucleosis as a teenager, was Anne Ursu’s Not Quite a Ghost. While it wasn’t exactly a one-for-one exchange – Not Quite a Ghost is middle grade fiction, to begin with, so the main character, Violet Hart is a few years younger than I was, and that does make a real difference – Ursu so vibrantly & devastatingly captures the destruction of this young girl’s life via a random illness that the difference it makes is that it’s even more damaging, which I didn’t know was possible. I felt worse for Violet than I did for teenage me, basically, who at the very least didn’t have to move to a new house, or deal with the changing dynamics of new middle school friend groups.

Another thing that should set the book apart is that it’s also a real ghost story – a story that is both about a haunted house, and such an adept deconstruction of The Yellow Wallpaper for younger readers that I just know when they encounter the actual novel later, not only will they swiftly recognize the similarities, but they’ll understand the original more keenly. And I only say that it should set the book apart because the metaphor of haunting and possession and something being so out of your control & completely overwhelming at the same time is such a perfect match for what it feels like to encounter chronic illness for the first time that it in no way made the story feel less intimately familiar to me.

Horror as a genre has long told the story of our fears about our own bodies, and about the human condition, but I think there’s something about telling that story with and TO children that boils it down to the bare bones and lays it out so blatantly that it can’t help but be exponentially more painful. I also think that there’s just something about middle school – the age, the transitions, the hormones, the friend group changes, the “what is my position within my family” feeling as you are no longer a little kid, but you’re not yet a big kid – that is so universal that you don’t necessarily need the experience of childhood chronic illness to understand and enjoy all aspects of this book. The balance between these two – the universality of childhood & the ‘uniqueness’ of abrupt chronic illness in childhood – is so delicate & Ursu weighs and manages it so dexterously, I was honestly a little jealous.

In these days when Long Covid has overtaken asthma as the number one chronic illness in children, though, a book like this is an invaluable resource. Terrifyingly so. Unnecessarily so. Heartbreakingly so. Books like this are more relevant & more essential now than ever. Violet’s experiences of getting sick & feeling better, then feeling worse, then just having random symptoms pop-up that she didn’t understand, and having that continue and worsen until she eventually couldn’t get out of bed is going to be the story of so many of our kids, as they deal with the repercussions of repeated Covid infections. It’s already their story. It was my first story of illness/disability, thirty years ago last month, and it was Anne Ursu’s story, as well, as she explains in her author’s note.

Having invisible illness own voices authors perspectives on these types of subjects is going to be invaluable in the current health crisis, and Anne Ursu’s is striking. It’s genuine & vulnerable, and never veers into the condescending or the trite, as too often happens when people are writing for younger audiences. The fact that this is happening to kids is SUPPOSED TO BE more traumatizing, in all honesty – It’s supposed to feel haunting and awful and terrifying, maybe even more so to the adults who are reading along. Just by virtue of us knowing that so much of what Violet is experiencing:

- The medical gaslighting

“…said she could be having school avoidance or something. Meanwhile Violet can barely sit up! The doctor noted how swollen her glands were, but once the tests came back the doctor was like, oh it’s probably nothing. I told her that just because there was nothing on her test results doesn’t mean there’s nothing medically wrong, and she said parents are often in denial, but usually when they think about it, they want their child to feel better more than they want this to be a medical problem….basically pronounces my Violet hysterical.”

- The friends not understanding the cyclical ups and downs of her symptoms

“How come whenever you’re supposed to hang out with us, you act like you’re sick?” “I . . . What?” “You’re always sick when it’s time to hang out, and then you’re magically better when it’s not.” She was bright red now, fuming. “That’s not how sickness works.” Violet’s mouth hung open. She wanted to say something, anything, but all the words had left her head. Paige stared, blue lips tight and twitching. One moment. Two. “Whatever, Violet.” And she turned and walked away.

- The snide comments from her teachers

Here’s our invalid, back again!” Mr. Bell said when she walked in, voice booming. He laughed, and out of the corner of her eye, Violet saw Paige smirk. Heat rose up in her cheeks.

- The way her mom worries and tries to hide that she’s worrying

Violet stared up at her. She swallowed. She felt like a collection of old bones. “Mom,” she said quietly, “I don’t think I can walk that far.” Her mother gazed at her then, face completely still, as if she were afraid what it might show if she moved it. “Okay, baby. I can get a wheelchair,” she said. “Just wait here.

- The way that literally nothing about her body makes sense to her anymore

Listen to your body. It was such a strange phrase. Wasn’t it her body that was supposed to listen to her?

Violet opened her mouth to scream, but no sound came out.

What could she do? She was a prisoner to this room like she was a prisoner to her body. And the girl in the wall was not wrong. Violet’s body was useless, a lump. She was useless, a sack of bones and parts. And no one could figure out what was wrong with her. No one could help her. Not with whatever was wrong with her body. And not with the thing in the wall. She was helpless.

- All of that and so much more, are simply Not. Her. Fault. and yet she’s experiencing it all as not only her fault, but potentially her fault via something she’s ‘making up’ or exaggerating or ‘wants’,

We as adults are also lucky enough to experience this secondhand trauma of wanting to explain it to her, to reassure her, to tell her mom the words she needs to hear, to help her understand it all better.

Or maaaaybe that’s just me. Cuz, like I said, medical PTSD, and no small amount of really over-identifying with a character happening & freely admitted to on my part. I remember needing the elevator key in high school and a teacher laughingly asking me if I wasn’t “limping on the other side yesterday.” I remember my friends being hurt I could go to biology but never made it to lunch. I remember the look on my mom’s face the first time I crawled out of my bedroom to get to the bathroom in the morning, because I simply couldn’t stand up, and I would pay any amount of money, at any ridiculous rate of interest, if I never had to see that look to begin with, and if I never had seen it again. But I have, as my body has continued to fail, and the answers for why and how to stop it still don’t come, and it’s awful. And none of that is something that fifteen-year-old me had the coping skills for, so bless Anna Ursu for acknowledging that 10-yr-old Violet probably wouldn’t have them either.

There was a point it the book, about three quarters of the way through, where the haunting starts to ramp up in intensity, and Violet’s illness starts to make it clear that it, also, is going nowhere, that I literally said, out loud, to my nephew, who just happened to be in the room with me, and had no idea what I was even reading “If this girl gets magically better once the house stops being haunted, I will throw my phone out the *expletive deleted* window.” (I was listening to the audio version, via my library.) At the time, I didn’t know about the author’s own experience with chronic illness, and I also have, like I said, 25 years’ worth of both good & bad disability/chronic illness representation in books, and the echoes of the really bad ones are constantly replaying in my mind: The fantasy & horror genres may have more disabled characters than other genres, but in my experience, that also means they do them dirty more often. I cannot begin to enumerate how often, a la the un-Oracle-ification of Barbara Gordon, a disabled character is ‘rewarded’ with the elimination of their disability/illness*. Which has the handy side effect of erasing the actual humans that exist with these, or similar, conditions, who had felt represented (perhaps for the first/only time) by said fictional character/s. And while Violet would no doubt have felt much improved if clearing the ghosts from her attic room had also magically cured her invisible illnesses, the damage it would have done to the actual human children (and previously traumatized adults :ahem:) is, to my mind, more important. Luckily, when you get authors who’ve likely experienced that same sort of erasure themselves, they tend not to perpetuate it, and I think you could guess how different my review might be if Ms. Ursu had.

The actual conclusion of the story? Is SO satisfying, in so many ways, and you can stop reading here, if you don’t want any actual spoilers, but….Violet unhaunts herself & her house by

- Remembering who TF she is (via pop-culture, which is can be a plus for me, in books for kids – let’s not pretend they don’t know who Ms. Marvel is, thank you very much).

- Reaching out to the community she’s trying to build, and that community reaching back to her (Building your own Scooby Gang, for the win!)

- Not asking her parents for help *Listen, as a grown up does this frustrate the HELL out of me? Absolutely. As a reader/consumer of culture, do I understand the constraints of the genre? Also, absolutely. The Stranger Things kids couldn’t immediately just ask their mom’s for help, because who tf was going to believe them that Demagorgons were kidnapping their friend? Circa 198whatever? Not a single one of them. (Joyce Byers is a different kettle of fish, and we can talk about why some other time.) Violet’s mom is actual uber supportive when it comes to her illness, in the face of more than one disappointing or dismissive doctor. (Which is sadly not true when it comes to all families facing invisible illnesses, which we could also talk more about in comments if you want.) But: Violet’s doctors have *already* put into Violet’s mind that maybe she’s making up this ‘whole not being able to stand up sometimes’ thing, the ghost itself is saying things like “What’s more likely, Violet? That you have an illness that somehow eludes the technology and expertise of every doctor you’ve seen so far? Or that you’re not really sick?…” Maybe that’s why everyone thinks you’re faking it. It’s such a peculiar malady”….”They won’t believe you; They’ll leave you like your friends did.”, and now she’s supposed to ask her mother to go another giant leap forward and believe that not only is her body betraying her in a way not even doctors understand but their new house haunted, AND the ghost in her walls wants to take over her body, specifically? Nope. I have no problem believing that this child was like… “Absolutely not, I’m on my own here.”

- Overestimating her own abilities at least once. She’s a child. A SICK child. And yet she’s trying to Ghostbust on her own? And that’s not gonna backfire at least a little bit? Nah… I’m glad Ursu shows these parts to, or else how unauthentic would it be?

- Overcoming anyways. Because I’ll tell you what. Sometimes you just do the thing, you have no other choice. And kids with chronic illness? Do that on the daily. You never met a group of “I will power through until I can no longer power through” people more than sick kids, and that absolutely sucks, and has a lot of ableist over/undertones, but is also realistic as hell & needed to be included. It’s also just part of both story conventions & horror conventions that the Final Girl has to pull off the impossible, it’s just that it’s not often that ‘impossible’ includes being able to move your body when it absolutely does not want to.

- No magical cure, but a ‘unicorn’ doctor. In the chronic illness community, when a doctor sees us & can actually get it, we call them unicorns, and, Violet manages to get her ‘unicorn’, in the end. When he says “Violet, I’m sorry. That sounds awful.” about how she’s been feeling, I wanted to throw him a party. And when he ends with the absolute banger of “If they can’t see something wrong immediately, they assume there’s nothing medically wrong at all. This is a failure of education, a failure of empathy, and mostly a failure of he health-care system itself. I’m very sorry you were treated this way.”, I definitely only almost cried.

Anyways, this was both the best and most personally traumatic book I read this year, and I recommend it to every single person if only for the reason that SOMEBODY you know is going to be impacted by an energy-limiting post-viral disease soon, if they are not already, and you should know it feels. I’ve spent 20-ish years using big adult words to discuss how that feels, but sometimes people need to see it at its core, and that’s what Ursu has done so perfectly here. She’s distilled the experience of Long Covid, and MECFS, and POTS, and so many other infection-related post-viral illnesses (and other chronic illnesses) down to their barest essences and said: Here, this is what this feels like, this is how some of you react, and how much it hurts us, and this is how you could react and how much it would help. I can’t think of a more important time for a book like this to be read, and if you think I’m not gifting it for Christmas, you don’t know me at all.