It’s great reading a book where you’re not 100% sure what the author thought of his subject; it makes you not 100% what you think of the book.

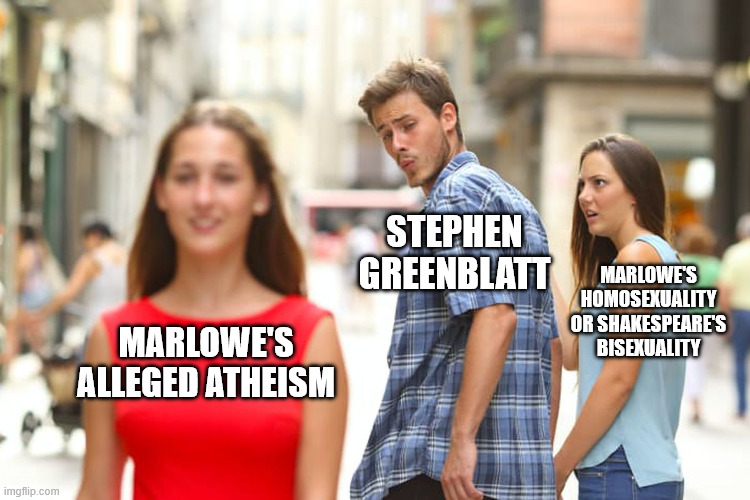

As you can’t tell from the title, Dark Renaissance is about Christopher Marlowe, Shakespeare contemporary who had a brilliant albeit brief career, dying at the age of 29 during an alleged brawl over a bill. There is not a whole lot of information about Marlowe available (even the possible sole portrait of Marlowe has not been actually been proven to be him), but that doesn’t matter here; Greenblatt does his best to conjecture and presume. Too bad that conjecture and presumption is mostly about his possible spy work for Francis Walsingham and the alleged atheism that might have led to his death, not his work, his life, or being as out a playwright as you could be in 16th century England. Which is okay, because he also takes the potential bisexuality of Shakespeare’s sonnets and turns it entirely into a platonic, totally just idle flattery of a potential patron. Because half those sonnets can seriously be taken in a “two Elizabethan dudes, standing 2 meters apart because they’re not gay” kind of way.

The main proof Greenblatt has to Marlowe’s atheism is that a note containing references to Marlowe’s plays was pinned to the door of a church in attack of the worshippers, some man who had tried to have Marlowe killed once previously said so, and a former roommate while under torture “confessed” to it; steadfast proof that all is. Not that the conspiracy ends there; Greenblatt also goes on to work up a theory that the bar brawl was a hastily covered up murder (most likely), ordered by Elizabeth I (the “heretic” daughter of a “heretic” King; bias anyone?) a la Thomas a Becket (uh…what?).

But that is the main hanger of the entire book, Marlowe’s atheism, and potential spy work, and how everything he wrote was atheistic at heart. Everything was “Marlowe the atheist wrote his atheists plays atheistically, after waking in his atheist bed and eating his atheist meal.” I mean, when you can discuss the overt homoeroticism of Edward II, and the covert homoeroticism of Faustus (said to be the most biographical of Marlowe’s work), but can’t discuss the orientation of the author. As far as I can tell, Greenblatt thinks he was married to his work.

It was mildly interesting, if a bit dry, though the word I’d say fits it best would be meandering. Greenblatt does not have a lot of information on the subject, and he tries to hide it by wending you through Marlowe’s life, hoping you never notice he’s saying very little, and repeating what he has said multiple times different ways. Filled in with Shakespeare, Walter Ralegh, England’s attempt to “civilize” Virginia, the British School system at large, religious difficulties in England at the time, and how much Elizabeth was mutton pretending to be lamb.

If you’re expecting a book about Marlowe, I might go elsewhere. But if you want a book about 16th century England, its spy networks and its views on Atheism, and how Shakespeare learned to be basically a cipher under the guise of a biography of Christopher Marlowe, pick this up.