CBR 17 BINGO: “N” (for Night)

CBR 17 BINGO: “N” (for Night)

Double BINGO! Across: B, I, N, G, O,

Down: Black, TBR, N, Family, Citizen

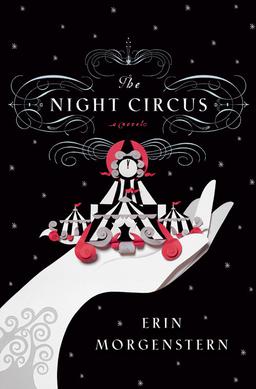

The Night Circus is a much beloved novel that, on paper, seems like it has everything that should appeal to me: a Victorian timeframe, a magical setting, an air of mystery, an understated romance. I admired the author’s creativity, particularly in the way she weaves fantastical elements into the circus; yet, I felt a bit let down by the fact that I wasn’t eager to pick up the novel and read at every free moment, as I’m likely to do with books I really love.

The story begins in 1873, when the illustrious magician Hector (stage name, Prospero) makes a wager with a rival enchanter, Mr. A. H.— pitting Hector’s newly discovered daughter against an opponent of A.H.’s choosing. The details of the wager are vague to the reader, but presumably the pair of old magicians has done this before. A.H. adopts a promising orphan and trains him in his own brand of magical arts, while Hector tortures his daughter Celia with exercises like slicing her fingertips and forcing her to heal them up again with magic (clearly the magicians are also vying for worst parent of the year as they prep their protégés for the upcoming competition). When Celia and Marco (A.H.’s ward) reach early adulthood, they both become attached to the Le Cirque des Rêves, or the Circus of Dreams, a traveling circus that appears in towns without warning, stays in one location for an undisclosed period, and is only open at night. Celia performs as an illusionist, while Marco operates behind the scenes as the main assistant to the owner and creator, Chandresh Christophe Lefèvre.

Unbeknownst to their guests, the circus operates on real magic rather than clever illusion and, over time, Celia and Marco add attractions using their own special brands of magic. Both know they are in a competition, but even to them the details are vague. At one point Prospero tells Celia, “I have told you all the rules you need to know. You push the bounds of what your skills can do using this circus as a showplace. You prove yourself better and stronger. You do everything you can to outshine your opponent.” The pair are not even told who their opponent is, though Marco picks up on it fairly quickly, with Celia taking longer to recognize her competition. To the old magicians’ chagrin, the young pair form an attachment and start building on each other’s work, “collaborating” to enhance the circus.

The tale is supported by a compelling cast of characters, including the stately Madame Padva, the costume designer whom everyone thinks of as an “aunt”; sisters Tara and Lainie Burgess, who help design the atmosphere and small details; Ethan Barris, head engineer and architect; mysterious contortionist Tsukiko. Each of them are integral to the running of the circus and start to feel the strange effects of it. There’s also a young fan named Bailey, who seems to have nothing really to do with the circus, except that there are chapters dedicated to him, so the reader recognizes pretty quickly that he’s going to be important down the road.

One of my issues with the novel is the way it’s told in a slightly non-linear fashion. Normally, I am 100% on board for non-linear storytelling. However, this story jumps from the activity going on with Celia and Marco to the slightly-in-the-future experiences of Bailey visiting the circus. The gap in years is small enough to be somewhat confusing, so that sometimes I had to double check whether we were truly in a future period or whether the story had simply advanced further than expected between chapters. As the story progresses, that gap in years gets smaller and smaller until they converge. It sounds like a reasonable approach, but again, it didn’t quite work for me.

I also felt like there wasn’t enough explanation of the differences between the two schools of magic. This whole competition comes down to Hector and A.H. wanting to prove which theory is better, but the novel doesn’t do enough to explain those theories. We can assume some based on Celia’s and Marco’s approaches, but I was left wanting more. Also, the competition doesn’t remotely prove which school of magic is better, but I guess we can chalk that up to Hector and A.H. being horrible people.

I can understand why people are enthusiastic about The Night Circus, and I wanted to like this novel more than I did. I liked it fine, but I don’t see myself ever rereading it or becoming part of its ardent fanbase. That said, if Le Cirque des Rêves ever shows up in my city, I’ll be there in black and white.