Bingo: “G” And with this I black out my Bingo card!!

Bingo: “G” And with this I black out my Bingo card!!

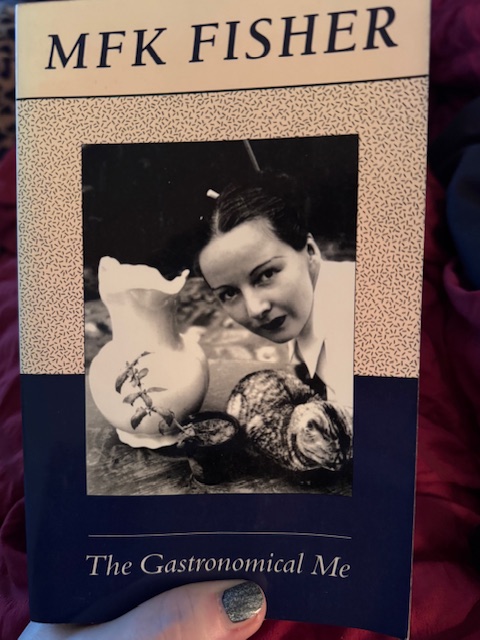

MFK Fisher’s The Gastronomical Me is a feast. Fisher transmits her memories through the lens of food, in which she takes the most sensual pleasure. Raised by a grandmother who saw food as strictly utilitarian, Fisher remembers her saying, “‘Eat what’s set before you, and be thankful for it,’ Grandmother said often; or in other words, “Take what God has created and eat it humbly and without sinful pleasure.” Fisher, fiercely independent and fascinated by the world, grew into a woman who reveled in sinful pleasure.

I normally greatly dislike memoir (not entirely sure why), but Fisher’s book of essays revisiting parts of her life from 1912 to 1941, enchanted me. Fisher is an incredible writer, with an eye for vivid details and strange moments that bring her work to life. It was not just that the meals (and lots of alcohol) sounded decadent and compelling, but her life–one of great privilege–was filled with love, travel, unusual encounters, grief, and passion. Even when Fisher can’t remember a meal exactly, she perfectly remembers the feelings it evoked in her.

Fisher writes with no embarrassment, whether it’s about her own charming solipsism or awkward moments, such as the time she goes to help a woman lying naked in bed and bereft about her lover. There’s a certain bloodless yet fervent emotion to Fisher, as when she somewhat cruelly describes another woman:

She was a stupid woman, and an aggravating one, and although I did not like her physically I grew to be deeply fond of her and even admiring of her. For years we wrote long and affectionate letters, and on the few times I returned to Dijon we fell into each other’s arms…and then within a few minutes I would be upset and secretly angry at her dullness, her insane pretenses, and all her courage and her loyal blind love would be forgotten until I was away from her again.”

Fisher is capable of telling serious stories as well as effervescent ones. There is a disturbing story where she and her lover are on a train at the beginning of World War II, when two Gestapo are bringing a prisoner back to Italy. They later hear a crash, as the prisoner breaks a window for an unsuccessful escape. Soon after, he cuts his throat on the broken window pane, rather than be returned to what is certain to be a grim fate. Fisher tells this story without embellishment or drama, which makes it even more effective. She closes the story with this:

We knew for a few minutes that we had not escaped. We knew no knife of glass, no distillate of hatred, could keep the pain of war outside. I felt illimitably old, there in the train, knowing that escape was not peace, ever.”

Fisher is a sensualist with sharp observation skills. Her descriptions of food and cooking and communal meals are delectable (she makes buttered peas sound ambrosial). Her essays were very entertaining and made me nostalgic for a past I never lived.