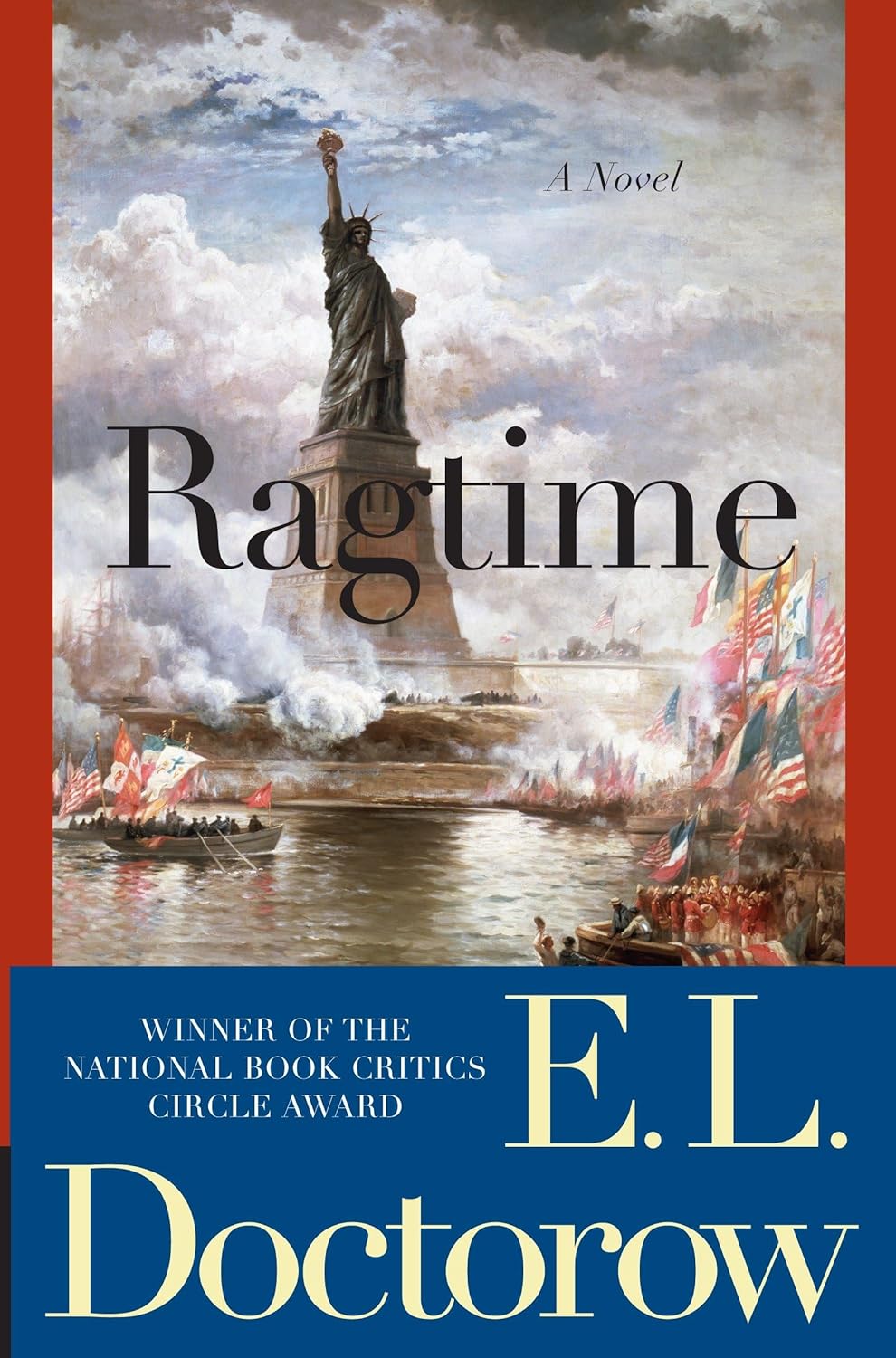

With the revival of the Tony-Award winning musical just recently opening on Broadway (I have tickets for later this week!) I thought it was a good time to refresh my memory of E.L. Doctorow’s 1975 novel, Ragtime. I first read the novel at the suggestion of my father somewhere around 20 years ago, so I had no recollection of the plot and characters at all, really.

The plot is a bit hard to summarize. Doctorow takes a sort-of panoramic approach to American life from roughly 1906 to the start of World War I. With some excursions to peek into the lives of famous American figures like J.P. Morgan, Harry Houdini, radical Emma Goldman, or showgirl turned tabloid object Evelyn Nesbitt, Doctorow mainly focuses on three very different families. The main thrust follows a prosperous household in New Rochelle, NY whose members are only known by their relationship to the little boy who lives there. Father is a successful entrepreneur who made his fortune selling American flags, bunting, and fireworks. Mother is a housewife who proves surprisingly capable of running both home and business after Father secures a place on Commander Peary’s North Pole expedition, while Mother’s Younger Brother works with Father at the fireworks factory, harboring radical ideas as explosive as any of the firm’s offerings.

After Mother makes a shocking discovery in the garden one day, the family’s lives intersect with those of Sarah, a poor, frightened Black woman, her infant child, and the child’s father, a successful piano player named Coalhouse Walker, Jr. After both Coalhouse and Sarah are subjected to gross injustices based on their race, the Family find themselves in a compromised position, knowing that what happened to their friends is wrong and should be addressed, but worried about the risks to their comfortable, safe existence that would come from protesting too loudly on their behalf.

While the disparate reactions of Father, Mother, and Mother’s Younger Brother are fit for serious discussion, Doctorow disappoints the modern reader by rendering Sarah and Coalhouse as flatter characters without as much humanity and depth. Coalhouse in particular could use more characterization through dialogue or internal monologue. He is a fascinating character based purely on his actions, but Doctorow too rarely lets the reader know how he thinks.

The third family Doctorow focuses on is comprised of the Jewish Tateh and his unnamed daughter. A widowed immigrant, Tateh barely makes a living through his extraordinary talent for making silhouettes. As his skill attracts more attention, he becomes prosperous and happy, though it’s clear that he does so largely by abandoning the political ideals he cherished so dearly when he was poor. Tateh and his daughter only glance on the main storyline of Ragtime, but comprise a useful counterpoint to both Father’s old-money Americanness and Coalhouse’s story of oppression and injustice.

Ragtime will lose points with most modern readers for the short shrift it pays to its Black characters, but it is an entertaining journey through the past. Doctorow prioritizes style and feel over characterization, attempting to catch the zeitgeist of an era. It’s ambitious and occasionally very satisfying, with obvious caveats.