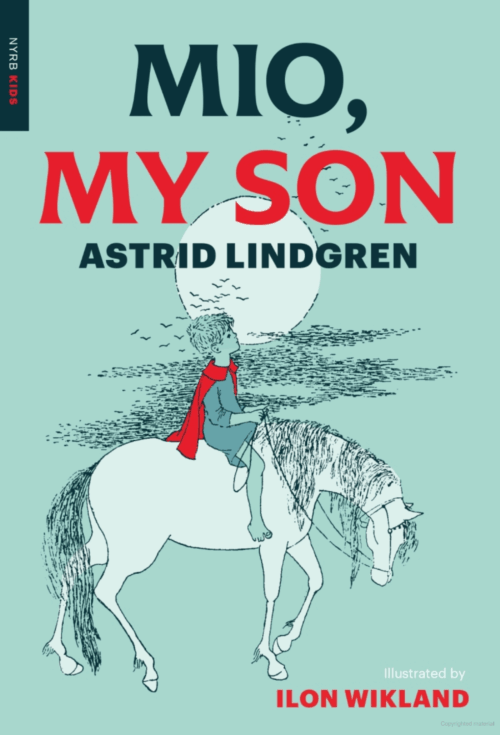

This is the 7th book in our read-aloud journey of 2025. (Previously featuring: The Hobbit, Travel Light, Mr. Popper’s Penguins, Jenny and the Cat Club, The Dragon of Og, and The Miraculous Journey of Edward Tulane.) Astrid Lindgren is most famous for Pippi Longstocking, but I was enchanted with the cover of this little book so I decided to read this one first.

This is the 7th book in our read-aloud journey of 2025. (Previously featuring: The Hobbit, Travel Light, Mr. Popper’s Penguins, Jenny and the Cat Club, The Dragon of Og, and The Miraculous Journey of Edward Tulane.) Astrid Lindgren is most famous for Pippi Longstocking, but I was enchanted with the cover of this little book so I decided to read this one first.

Andy is an orphan who lives with his aunt and uncle in Stockholm. He is lonely and unloved, save for his neighbor friend Ben and a cart horse who lives near his house. But, we learn on the first page, Andy is actually Mio, and he has been swept away, he’s disappeared, and he now lives with his father, who happens to be the King of Farawayland, where he is loved and cherished–and where he finds that he must, as the King’s son, fight a great evil. The first half of the book is mostly Mio discovering how awesome his new life is in Farawayland, how loved and cherished; the second is his very scary journey with his best friend Pompoo, to battle the evil Sir Kato, as foretold in the prophecies.

Lindgren uses a lot of repetition in this book: the king is always “My father the King” and Mio is always “Mio, my son.” When they are on their journey, Pompoo repeats, “If only we weren’t so small and so alone!” at every turn, and honestly, you can’t help but agree. They are given The Bread that Satisfies Hunger, one of many turns of phrase that made me think of Pilgrim’s Progress. Mio and Pompoo acquire many magical objects – a sword, a cloak, a horse, a spoon, without much explanation or preamble. The characters they meet along the way also repeat their warnings and stories. At first I found this a little bewildering – other stories would have spent much more time justifying the invisibility cloak, or explaining the magic that turns stolen children into Bewitched Birds! But as the story went on, I felt the rhythm working in a way that reminded me of oral storytelling tradition – you can’t gloss over the repetitions when you are reading it out loud, you have to READ them, and as you read them over and over, the different possible meanings become apparent. Mio, My Son really works as a read-aloud for this reason.

And by the end I saw what Lindgren was getting at – the cloak and the boat and the sword of fire etc. etc. are almost incidental to the story, although they are classic adventure tropes that spur the plot along, especially for younger readers whose imaginations can easily grab onto these images. What really matters to this story is that Mio is utterly, completely, thoroughly, unquestioningly loved and trusted by his father and his best friend. At first he says “my father the King” as if he needs to remind himself of this astonishing fact – and by the end he is saying it as a fact that he knows in his bones. He is small and scared, but the deep knowledge of that love gives him the strength to do what he needs to do. When I write that sentence in this review, it sounds trite; it works because Lindgren never actually says it outright. She writes it into the the structure of the book, and the melancholy tension between Mio’s current and former lives, between what he wants to do and what he must do, and between his joy at finding his father the King and the sadness of leaving on his quest. She writes it into the repetition of the phrases, and into the simplistic, parable-like structure of the book.

At 10 years old, my son is becoming a little more interested in more complicated plots, I think; he liked this one but didn’t seem to be deeply invested. However, when we finished the book, my 7 year old literally applauded. She loved it. This tracks with who they are as readers, but I think it also tracks with the ages – this is a book for a little younger audience; it’s a book that gives a young reader — I think 5 is not too young — the benefit of the doubt, that reassures them of their strength and worthiness, that tells them that they can do impossible things because they are loved.