CBR 17 BINGO: Arts, because Gustav Klimt and his contemporaries figure into the plot

CBR 17 BINGO: Arts, because Gustav Klimt and his contemporaries figure into the plot

Double BINGO! Across: Arts, Borrow, Citizen, Work, White

Diagonal: Arts, Red, N, Diaspora, Rec’d

I’ve been a Christopher Moore fan for a long time. (Who doesn’t love Lamb and The Stupidest Angel?) Not all his novels are brilliant, and even in my own household we don’t always agree on what works and what doesn’t (I love Fool and its sequels, while my husband doesn’t care for them at all; he loves Sacré Bleu, which I consider a lesser Moore). Nevertheless, even Moore novels that I don’t particularly adore are usually worth reading; Anima Rising was the first one I considered quitting.

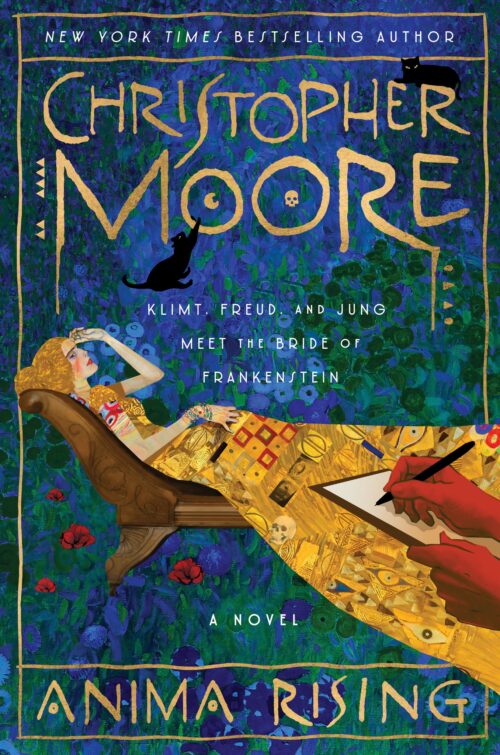

The plot summary is on the cover: Klimt, Freud, and Jung meet the Bride of Frankenstein. It sounds like a worthy topic and promises typical Moore zaniness. Moore includes a trigger warning that “Herein are described incidents of sexual assault, violence, and profanity, as well as references to sex and sex work.” Okay, I’m not a prude; after all, I once described The Lust Lizard of Melancholy Cove, in which a C-movie actress has an inappropriate relationship with a sea monster as “good, clean fun.” Nevertheless, I underestimated the general ickiness of this novel. Klimt, you see, painted many young models, who lived with him and were expected to also sleep with him (this is historical fact). There are lots of very young girls walking around naked throughout this book, as well as suggestions of incest between Klimt contemporary Egon Schiele and his sister Gertie (which may or may not be true; he did paint a lot of nude portraits of his sister). When we meet Judith, the bride created by Frankenstein for his creature, she talks about her past in which she was repeatedly raped by the monster. I don’t object to any of these topics in principle, but let me pause here to remind you that this is a comedy.

I want to be perfectly clear about something: I firmly believe that no topic should be off limits for comedians. Humor is a powerful weapon, and when we can laugh at something horrible, we rob it of its potency. Here’s the caveat, though–the more sensitive the topic, the harder it is to make jokes about it funny. And quite frankly, this book is not funny. Like George Costanza’s mother, I never laughed. Not a giggle, not a chuckle, not a tee-hee. I never went “Ha!”

Moore seems to have anticipated this reaction and addresses some issues in his Afterword. Of Wally, the model who totally got the shaft in real life, he says, “I can do nothing to correct the injustices of history. I could do nothing to change the circumstances Wally lived under, nor does it serve anyone to stand upon the self-righteous platform of progress and shout down about just how awful, unfair, and dehumanizing conditions were for a young woman of the time. . . . but what I could do was portray her as resilient, clever, loving, courageous, resourceful, and funny.”

In Moore’s weird way, he intends this to be a feminist novel, and indeed there are strong female moments: Klimt’s “acquaintance” Emilie is a model of independence; a strong bond of friendship and support forms between Wally and Judith; and, eventually, Judith goes Atomic Blonde on the thugs pursing her. But it takes a long time getting to the feminist core, and you have to wade through pages and pages of sophomoric jokes to get there. I know, Moore is all about sophomoric jokes, so maybe it’s me. . .maybe I’ve just grown tired of the shtick.

There’s a lot more in this novel that I haven’t mentioned–the Underworld, a Raven god, a dog named Geoff, some Klimt cats, a feud between Freud and Jung. All these elements could have added up to something hilarious and brilliant. Maybe Moore just bit off more than he could chew with this one. All I know is I’ll be happy if I never have to hear the term “fuck-puppet” again.