Robert Louis Stevenson, the author of Treasure Island, Kidnapped, and The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde among many other works, was born in Scotland in 1850 and died in Samoa in 1894. In those forty-four years, he packed in a lot of travel alongside all that writing. Much of the travel was for health reasons: at the urging of doctors he was constantly looking for more temperate climates to ease his frequent attacks and hemorrhages. Confined to his nursery as chronically ill child, he turned to imagination and storytelling for escapism, and managed to turn his life into a real adventure to rival the stories he put on paper.

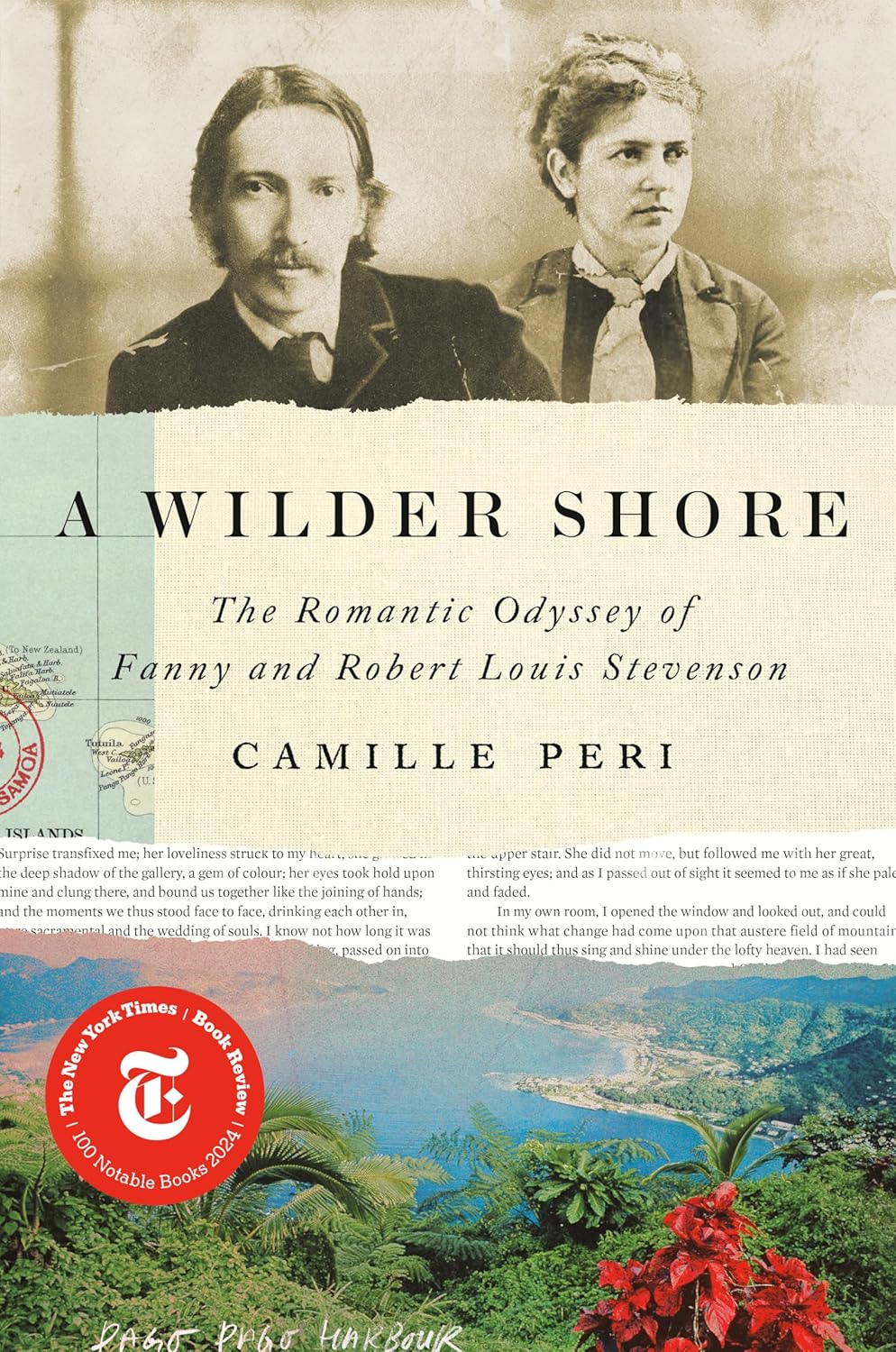

His companion for much of his adult life was his wife Fanny, an American who was ten years older than Stevenson and came into the marriage with two living children from her previous marriage. According to Peri, prior biographies of Stevenson have treated Fanny poorly, shortchanging her for her role in her husband’s literary output, ignoring her own writing career, and castigating her for alleged selfishness and foolishness. While Peri herself acknowledges that she lacked her husband’s talent and flair, she still believes that Fanny (born Frances Van de Grift) deserves to be taken seriously.

Therefore, she starts her book with Fanny’s story. Born in Indiana, she married young to a promising law clerk who sadly got wrapped up in the silver mining craze and dragged his young bride to Nevada. There, he proceeded to essentially abandon his wife whenever he felt like it, forcing her to raise the children on her own while he took up with a series of younger mistresses. Remarkably for the time, Fanny stood up for herself and managed to travel in search of a better life for herself, first to San Francisco and later to Europe, where she studied painting alongside her teenage daughter and made a name for herself in society as a charming hostess. Eventually, she met Robert Louis Stevenson before his first real successes as an author. Despite their age gap and the minor sticking point of her still being married, Louis, as he was known to his friends, was immediately besotted.

Once they were married, Fanny and Louis tried to have a more egalitarian marriage than was typical of the time, though Stevenson’s frequent bouts of illness essentially forced Fanny into a caretaker role. Eventually, Stevenson found greater and greater success with his fiction, culminating with the massive financial success of Treasure Island and especially Jekyll and Hyde.

Stevenson traveled in a circle of fellow literary men, befriending the likes of Henry James and William Ernest Henley. Many of these men, with James a notable exception, belittled Fanny’s writing, considering her deluded and blaming her for any downturn in their friend’s fortunes or mental state. As Peri points out, Stevenson himself was largely supportive, with occasional outbursts of impatience and irritation largely overshadowed by his tremendous love for her.

Stevenson spent his last years in the Pacific, including a lengthy stay in Samoa, where he eventually succumbed to illness. I was hoping to learn a lot about his and Fanny’s time there, but by the time A Wilder Shore gets there, I was a little bored due to all the time spent discussing Fanny’s social life and her unsuccessful stories. Especially once you get to the part where Peri kind of admits that Fanny had a little bit of a habit of taking stuff from other writers without crediting them.

Perhaps A Wilder Shore suffers from the fact that it can be hard to dramatize the life of a writer, even one who traveled as widely and lived as vivaciously as Robert Louis Stevenson.