CBR 17 BINGO: Diaspora. The author uses the Jewish diaspora to illustrate the remarkable resurgence of Hebrew as a spoken language. You could also argue that Esperanto speakers form a diaspora.

CBR 17 BINGO: Diaspora. The author uses the Jewish diaspora to illustrate the remarkable resurgence of Hebrew as a spoken language. You could also argue that Esperanto speakers form a diaspora.

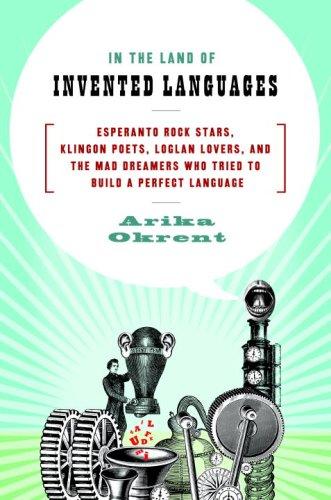

When you think of “invented” languages, you might immediately think of Esperanto, the late-19th century experiment in creating a universal language to bring people closer together. Or you might think about Star Trek geeks going all-in on their hobby by learning Klingon. Or you might ponder J.R.R. Tolkien’s elvish languages, created decades before he wrote The Lord of the Rings.

Yet in the Appendix to In the Land of Invented Languages, author Arika Okrent lists 500 languages created between 1150 and 2007, and she only stopped at 500 because, well, you have to stop somewhere and nobody really knows for sure how many languages have been “invented.” The story of invented languages is fascinating, brilliant, hilarious, and sometimes shocking.

First off, what do we mean by “invented” languages? Surely all language is invented? As Okrent, a Ph.D. in Linguistics, points out, “Who invented French? Who invented Portuguese? No one. They just happened. They arose. Someone said something a certain way, someone else picked up on it, and someone else embellished. A tendency turned into a habit, and somewhere along the way a system came to be.” Typically, language creation happens organically, over long periods of time. Except when some mad dreamer comes along and decides a new, better system is required.

Perfecting language seems to be a motivator for many of the visionaries who have tried their hand at language invention. Okrent admits, “Looked at from an engineering perspective, language is kind of a disaster. We have words that mean more than one thing, meanings that have more than one word for them, and some things we’d like to say that, no matter how hard we struggle, seem impossible to put into words.”

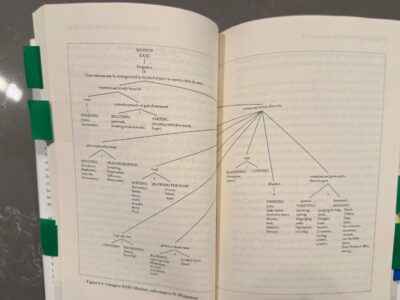

John Wilkins, 17th century co-founder of the Royal Society, was one such visionary who thought he could improve upon language by leveraging science and mathematics. In Wilkins’s view, the problem with language is that words don’t tell you anything about the word you’re defining. Sure, we know what a “dog” is (or a “chien” or a “perro”) because we agreed to a definition. But for language to be truly useful, a word has to not only “stand” for a concept, it has to define it. Wilkins started by organizing every word in the English language into a 600-page treatise filled with taxonomic trees. For example, he organizes every type of purgative action a human body can experience into one handy chart, to the delight of the author and 13-year-old boys everywhere.

Let he who has never looked up the word “vomit” in a Thesaurus cast the first stone.

Wilkins’s plan was to create a language of symbols that build upon each other. So for example, the symbol for “shitting” would be the symbol for motion + the subcategory for purgation + the subcategory for “gross” parts + the term for the opposite of vomiting. The result is the word Cepuhws.

You’ve got to be Cepuhwsing me.

While this new approach to language was not particularly useful in terms of helping people understand each other, Wilkins had unwittingly stumbled upon a type of thesaurus. Indeed, Peter Mark Roget, who would go on to publish Roget’s Thesaurus in 1852, was familiar with Wilkins’s work.

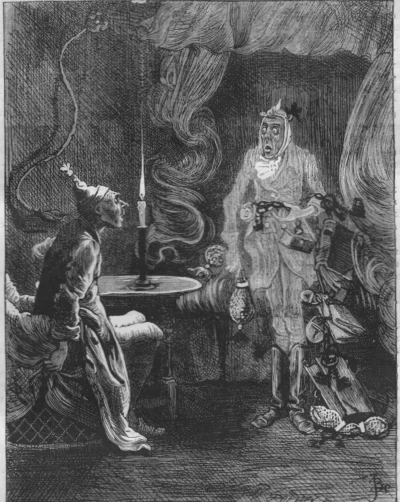

Other inventors thought that words were the problem, and symbols were the way to create a better language. In the 1940s, Charles Bliss created a pictorial symbol language called Blissymbolics. Although Bliss’s book was, in Okrent’s words, “full of rambling utopian philosophy and naive scientific theories (complete with references to Reader’s Digest articles),” Blissymbolics had a practical application: a school in Toronto for children with cerebral palsy were using it to communicate with their most non-verbal students. Blissymbolics was a blessing for these teachers and students, and Charles Bliss was initially ecstatic. However, he was also a bit. . .unstable, shall we say? When the school began making adjustments to his language to make it even more useful for the children, Bliss responded first by screaming, then by slandering, then by lawyering up. In spite of the school’s attempts to work closely with Bliss, in 1983 they paid him $160,000 for an exclusive, perpetual license of Blissymbolics. “That’s right. There’s no other way to put it: Bliss, self-proclaimed savior of humanity, stole $160,000 from crippled children.”

That Christmas, Bliss was visited by three spirits.

Others have felt that the way to improve language would be to simplify it by reforming spelling or removing grammatical irregularities. In 1930, C.K. Ogden, a Cambridge-educated “editor, writer, translator, and mischief maker” published Basic English. Ogden’s goal was to make English an international language by reducing it to 850 words.

95 years later, success!

Esperanto, created in 1887 by L. L. Zamenhof, has the noble purpose of bringing people of the world together through a common language. And to some extent, it’s been successful, or at least more successful than I ever realized. Esperanto has an estimated 2 million speakers across more than 100 countries and, to my surprise, even has “native speakers,” meaning that there are 2nd-generation speakers who learned the language from their parents. People attend Esperanto conferences where they speak nothing but Esperanto for days. They have a reputation for a sort of hippie-esque quirkiness, and the author’s descriptions of her visits to “Esperantoland” sound nothing short of joyful. Yet she also questions, “Is it ridiculous to believe that a universal common language will bring peace to the world? Of course it is. We have all the brutal evidence we need: the fact that Serbians and Croatians speak the same language did not prevent the bloodshed in Yugoslavia; the shared language of the Hutus and Tutsis did nothing to stop the massacres in Rwanda.” She concludes, however, that “The world may not need Esperanto, but it does need people who. . . are moved to act against the ‘enmity of nations.’ ”

In the Land of Invented Languages is insightful, interesting, and fun. Whether she’s describing her experience studying for and passing first-level certification in Klingon, or delving into the conjugation of “to menstruate” in Láadan (a women-centric language created by Suzette Elgin) or relating the warring factions of Loglan vs. Lojban (don’t even ask), Okrent is both thoughtful and hilarious. As someone who loves the English language in all its mad irrationality, I haven’t had this much fun with word-centric entertainment since the Blackadder episode where Samuel Johnson visits Prince George to patronize his new dictionary.