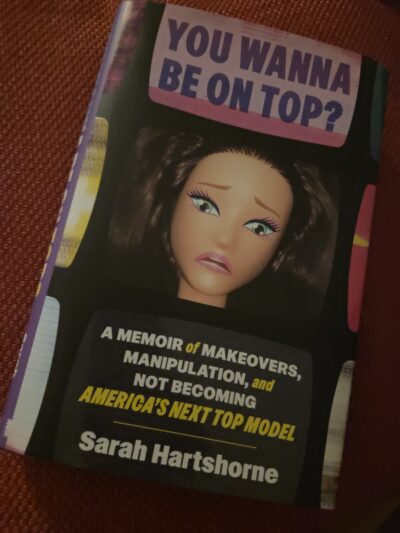

Bingo square: Border. This memoir is about the blurriness of the border between the real and fake, mainly on what we call reality television, but also within trauma-inflected memory.

The way I ate this up, as the youth who were born after Sarah Hartshorne’s stint on America’s Next Top Model (2007) would say. Of course, said youth would immediately identify the toxicity of the show (which took me well over a decade to figure out) and make a pithy 8-second TikTok call-out–although they might also arbitrarily designate some moments or characters as iconic. Who knows? I’m old and I watched this the first time around and I bought into a lot of bullshit.

What Hartshorne does is build a bridge across the border between  now and then, using her vantage point in the present to examine and contextualise her experience on the show, while acknowledging the shakiness of her memory. Whole scenes presented on the show didn’t happen the same in her memories; other things she blocked out. It seems almost facile to talk of the trauma of being on a fashion reality show–but Hartshorne convincingly explains that it’s there and it’s real.

now and then, using her vantage point in the present to examine and contextualise her experience on the show, while acknowledging the shakiness of her memory. Whole scenes presented on the show didn’t happen the same in her memories; other things she blocked out. It seems almost facile to talk of the trauma of being on a fashion reality show–but Hartshorne convincingly explains that it’s there and it’s real.

She takes us, then, behind the scenes of Cycle 9 in a way that is horrifying but also guiltily juicy, and reveals concerns about femininity and sexuality and body image and agency that are of their time–or have they shifted shape, the chopped-up narration of the confessional booth morphed into the surveillance and self-surveillance behind the glossy lives and #sponcon of social media?

I rewatched the season as prep for reading this, and the recurring emphasis on her body and how it would fit into the world of fashion is wildly troubling; Hartshorne’s musings on her body dysmorphia and the disintegration of her sense of self are well-written and disturbing. Hartshorne was in the peculiar position on the show of being a girl who was a few sizes bigger than the other models, but who kept getting scrutinised for supposedly losing weight, which would take her out of the construct of the plus-sized model category. But Hartshorne maintains that she lost max a few pounds over the course of the show. The border between the real and unreal isn’t just blurry here; it’s fully dissolved.

Hartshorne details her initiation into the world of ANTM, like a cult survivor, a comparison she directly evokes–this is the season where the girls are herded onto a cruise ship in Puerto Rico (and apparently kept in windowless conference rooms while NDA terms and conditions are hammered into them, reinforcing the message not just of discretion but absolute obedience to the rules and conceits of the show). The way Hartshorne describes Banks also evokes the supposed charisma of the cult leader:

“Is there something wrong with your back?”

This was more than just panel feedback. This was special. I wanted to bask in Tyra’s attention forever and never let it go. Say what you will about Tyra, but she is one of the most magnetic and compelling people I’ve ever met. Her gaze felt like the sun.

Granted, we were in the world she created, so of course she was the sun, the moon, the terrifying and mysterious universe. And now she was talking to me. And asking me a question. Which I was taking a really long time to answer. Like, uncomfortably long. Say something, Sarah. Answer the question. Tell her that you have scoliosis. …This is the kind of thing that reality shows love. Just say it, Sarah. The judges were looking at me expectantly.” (p. 131)

And this is the most interesting and insidious thing, the way that even though the girls at this point, having watched the previous nine seasons, or cycles–a term that emphasises the disposability of the models–are savvy about how reality shows work, and know that someone will be cast as the villain and another as the victim, and know that their words will be taken out of context, they still buy into it. Why wouldn’t they? A lot of them, as Hartshorne notes, are vulnerable, with damage in their pasts; they’re all very young. So the fact that knowledge does not in any way equal power here is fascinating to me (as are, of course, the details about how exactly the show is made, how the real is made to seem fake and the fake real, and, naturally, the behind the scenes dirt on what the judges and other recurring people are like from the contestant’s point of view).

Hartshorne is a wry and sympathetic narrator, unsparingly honest about her journey and her insights into the disconnect between her feelings, fears, and desires at the time and how she feels looking back. I would like a little more contextualisation regarding beauty ideals and image at the time–the early 2000s–and more sense of how the show fit into the reality TV landscape of that era (and what she thinks has changed since). But this is not just because it would help to make sense of her experience and memories, but because I’m genuinely interested in her thoughts on all of this, which I think speaks to how intelligent and engaging I think her writing is.

Title quote from Radiohead’s Fake Plastic Trees (1995)