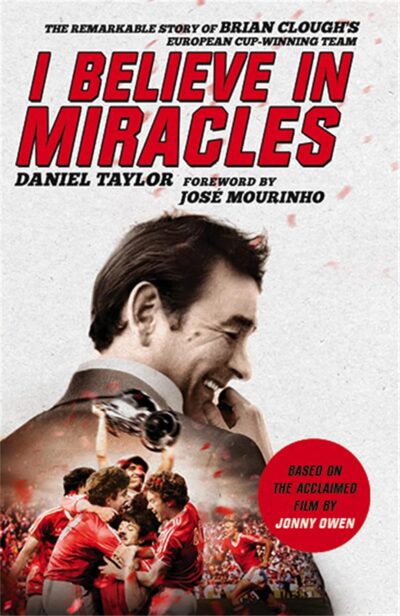

A few years ago, when I was trying to decide on an English Premier League team to commit to, there were a few reasons Nottingham Forest appealed to me. First, and I will not deny this, was the name. I also liked the uniform colors, and the fact that the home crowd sings a version of Paul McCartney’s Mull of Kintyre with altered lyrics. Mainly, I didn’t want to come in and pick one of the big six teams, because that’s not really who I am as a sports fan. (To be fair to all the American fans of Arsenal, Liverpool, the Manchester teams et al, it can be precarious rooting for a team more susceptible to relegation. When I first started supporting Forest, I was worried that they would fall into the Championship and their games would no longer be on television.) Though I didn’t want to be a front-runner, I also didn’t want to take on a team with no hope. I was therefore somewhat re-assured by learning about Nottingham Forest’s former glory: they won the European Cup in back-to-back years, something not many teams in England or anywhere else have managed.

Those teams were managed by Brian Clough, a legendary figure in the world of English football. Clough might be familiar to non-sports fans from his portrayal by Michael Sheen in The Damned United, which covers his incredibly brief and tempestuous tenure as the manager of Leeds United. Nine months after that humiliating career low, Clough, who had previously won a championship with Derby, took over the reins at Nottingham Forest.

Taylor does a wonderful job laying out the challenges Clough faced. Forest were a second-division club, and nearer the bottom of the table than the top. Ownership were spendthrift and unambitious. They were reluctant to even hire Clough in the first place. Attendance was low, the stadium was falling apart, and the team was short on players capable of playing in the top division. It was a bumpy transition at first, but once Clough was able to bring aboard his friend Peter Taylor as an assistant, Forest’s fortunes took off.

The working relationship between Clough and Taylor is a fascinating aspect of the story. Throughout their careers, they struggled whenever they were doing their own thing, but together they were magical. Taylor’s genius was for finding overlooked players and Clough’s was for making them into stars. Clough has a preternatural understanding of what each mad needed, endlessly pushing buttons and driving players nuts, even as they reached heights they had never dared to dream of for themselves.

Clough was certainly unconventional. The book is full of anecdotes of him cancelling practices to tell his players to go for a walk or to spend the day at the beach. He frequently encouraged the team to go out and carouse the night before a big match, up to and including the European final. He himself would usually skip a match or two per season to go on vacation with his family. He mostly got away with all of it, because he was charming and funny on television. He had a massive ego, best exemplified by how much he liked to tell the story of “the night Frank Sinatra met me.” He picked fights all the time, insulted opponents in the press, and drove people crazy. But he was truly beloved too. The book is full of players telling stories of Clough doing and saying things to them that would probably get any manager fired today, no matter their record, but to a man they insist they’d have done anything for him.

I’m not very familiar with the history of soccer, so the endless stream of player names and dates could be hard to keep straight at times, but Daniel Taylor does a good job for the most part of showing who the players were in full. Left winger John Robertson, so instrumental in both European Cup final wins, stands out the most. Despite a physique that looked unathletic, he commanded the ball perfectly and his decision-making made him quicker with the ball than many much faster players. Goalkeeper Peter Shilton, midfielder John McGovern, defensemen Kenneth Burns and Larry Lloyd are also fully-realized personas in the book. I was a bit disappointed not to learn more about Viv Anderson, Forest’s only black player and the first black man to play for the England national team.

I Believe in Miracles, which was conceived as a companion piece to a documentary of the same name, is a worthwhile read on its own. It tells a fascinating story in great detail and with a lot of humor. Even for someone without much interest in Nottingham Forest, it would be worth reading for its insight into Brian Clough, a truly fascinating figure unlike anyone in contemporary sports.