Bingo: Citizen. “[T]he questions we asked of Jews about their everyday lives in Nazi Germany concentrated more on how they got along with and were treated by the non-Jewish population in their communities and on their loss of identity as former patriotic Germans in a society that no longer considered them worthy of citizenship and eventually of life itself.”

Bingo: Citizen. “[T]he questions we asked of Jews about their everyday lives in Nazi Germany concentrated more on how they got along with and were treated by the non-Jewish population in their communities and on their loss of identity as former patriotic Germans in a society that no longer considered them worthy of citizenship and eventually of life itself.”

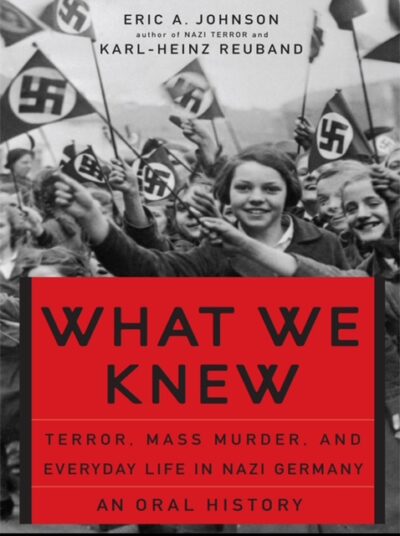

I picked up Eric Johnson and Karl-Heinz Reuband’s What We Knew: Terror, Mass Murder and Everyday Life in Nazi Germany because of the growing fascism in the US, which echoes the cult of personality president, craven government supporters, and most of all the persecution and disappearing of vulnerable minorities. As I discovered, there are all too many parallels to our current situation.

The authors did an in-depth survey and a series of interviews with German Jews and non-Jews who lived through the Third Reich, from approximately 1933 to the end of World War II in 1945. Their questions focused on everyday life under the Nazis, the use of terror, and the extent to which people knew about the systematic mass murder of the Jewish population. The first part of the book is divided into two parts: oral history interviews with German Jews and oral history interviews with non-Jewish Germans. The second part is a breakdown of the survey and interview results as well as some conclusions.

The Jewish Germans talk about the change in Germany when the Nazis came into power; a number of interviewees emigrated before the war and others lived through the war and Holocaust in Germany. Prior to 1933, many Jews got along with their non-Jewish neighbors. While anti-semitism certainly existed, it wasn’t until the Nazis came into power that anti-semitism violently increased year after year. The interviewees go into great detail about the rising anti-semitism, from renunciations to beatings to deportation to extermination. When talking about the knowledge of Jews being killed in the concentration camps, one interviewee says, “I don’t care that they say today that [“we didn’t know about it”]. Bullshit! We didn’t know in detail what was happening. They probably didn’t know that there were gas chambers in Auschwitz or in Treblinka, but they knew that the Jews were vanishing.”

The German non-Jews talk about how the German people initially embraced Hitler, as he solved rampant unemployment, built infrastructure, and enacted social welfare programs. Where “[m]ost Jews lived in perpetual or nearly perpetual fear of arrest during the Third Reich,” [most] non-Jews…experienced a very different Third Reich. Few harbored any fear of arrest even though they too often broke the [Nazi] laws in minor ways. Most knew instinctively that the terror apparatus was not intent on punishing them so long as they broadly accepted and went along with National Socialism, which most did.” It goes on to say: “Many people, therefore, retreated into their own private sphere and often turned a deaf ear to political issues. Unlike Jews, anti-Nazi activists, and other targeted enemies, however, they had the option of retreating in this way.”

The interviews conducted with the non-Jewish Germans revealed what they witnessed, what they suspected or knew about the camps, but also a curious shortage of anti-Semitic feeling. The authors write: “Probably our surveys and interviews with non-Jews uncovered so little evidence of overt anti-Semitic feeling because few people would ever want to admit that they once supported policies that eventually led to the mass murder of millions of Jews.” But in fact, “the faces of most of [the Jews’] German countrymen turned from friendship to indifference to outright anti-Semitic hostility…nearly all Germans went along–many actively, most at least passively–with the anti-Semitic policies and measures fostered by their government and offered no meaningful protest against them.” The authors do point out, however, that a meaningful minority of Germans provided aid to Jews during this time. However, this could not “compensate for the fact that a greater percentage of Jews received none.” As one Jewish interviewee remarked, “They just looked the other way.”

Among other conclusions, the authors make clear that at minimum a third and possibly half of the German population knew about the Nazi’s secret plans to annihilate the Jewish population. But even as witnesses, many Germans stated, “What can you do?” such as in this devastating account by a non-Jewish German who talked about seeing children in the Jewish ghettos:

The worst thing for us was to see the children, such tiny children, such poor little creatures, and how they would sit there holding out those tin cans. Their heads consisted only of eyes. But what eyes and what tiny faces. That was what was most distressing. You could have cried when you saw those children. It was dreadful. But what could you do?

This book was a devastating and thorough account of life in Nazi Germany and how its citizens–Jew and non-Jew alike–experienced it. It is not an easy read, but it is an important one. It reminds us that indifference, as well as hate, can lead to catastrophic injustice.