CBR 17 BINGO: Culture, because the culture of the pre-American Civil War South is prominent in this book

CBR 17 BINGO: Culture, because the culture of the pre-American Civil War South is prominent in this book

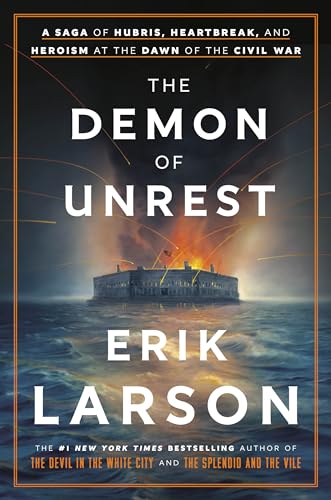

Erik Larson is one of my favorite non-fiction writers, and if American history is your jam, this is a must-read. Folks like myself who are less war-curious might still find it interesting; however, I felt it sometimes got bogged down in the logistics of pre-war strategy. I found the sections dedicated to the personalities involved and the beliefs of the times more interesting, and also more rage-inducing.

To understand the American Civil War, one has to understand that Southern planters called themselves “the chivalry” in the style of fictional works like Ivanhoe and Idylls of the King. Remember those words that appear on screen at the beginning of Gone With the Wind? “There was a land of Cavaliers and Cotton Fields called the Old South. . . .Here in this pretty world Gallantry took its last bow. . . . Here was the last ever to be seen of Knights and their Ladies Fair, of Master and Slave. . . . Look for it only in books, for it is no more than a dream remembered. A Civilization gone with the wind . . . .” That wasn’t exaggeration–Southern planters really saw themselves as the civilized gentry, and they recognized no irony in their ownership and dehumanization of fellow human beings.

Example? James Hammond, one of the most prominent proponents of slavery as well as the man who coined the phrase “Cotton is king,” kept detailed diary entries in which he “bemoaned the death of a three-year-old, not out of any sense of emotional loss, but because this was the seventy-eighth death in just under ten years.” This same paragon of virtue confessed in his diary to having sexual relationships with four of his nieces, aged 13 to 19, between the years of 1841 and 1843, while he was serving as governor of Georgia. Of course, this was the fault of the ladies involved, for “permitting my hands to stray unchecked over every part of them and to rest without the slightest shrinking from it.” The scandal that followed didn’t stop him from being elected U.S. Senator in the 1850s, which is all I need to know about the South’s concept of “honor.”

This book focuses on the five months between the election of Abraham Lincoln (November 1860) and the firing on South Carolina’s Fort Sumter (April 1861). It focuses on the tensions around Lincoln’s election (in spite of Lincoln running on a platform of preventing slavery from expanding into more states, rather than a promise to end slavery where it already existed); the heroic maneuvering of Fort Sumter’s Commander, Robert Anderson; and the push for secession by radicals like Virginia State Senator Edmund Ruffin.

One thing this book doesn’t do is analyze the causes of the American Civil War. Historians can debate this all they want; there is simply no getting around the belief by Southern land owners that slavery was not just acceptable, but was a “morally correct and beneficial institution.” William Howard Russell, an Irish journalist who covered the pre-war months and the war itself for the London Times recognized this fact and “marveled that the South seemed intent on staking its destiny on ground that the rest of the world had abandoned. ‘Never,’ he wrote, ‘did a people enter a war so utterly destitute of any reason for waging it.’ ”

Larson’s research is impeccable–so much of this book is directly quoted from the diaries of Hammond, Mary Boykin Chestnut (a major source in Ken Burns’ Civil War documentary), and others that one can’t credibly doubt the veracity. While there are some lighter moments–apparently Abraham Lincoln was a terrible speller who could never seem to spell “inauguration” or even “Sumter” correctly–it’s tragic for the mostly unspoken recognition that those who don’t learn from history are destined to repeat it. The seething hatred between secessionists and abolitionists and the hypocrisy of many elected officials are two of the themes that pervade this book. Add to that the wildly false assumption by both sides that a war between North and South would be so short that it would spill only enough blood “to fill a lady’s thimble,” and you have a history lesson we can’t afford to disregard.