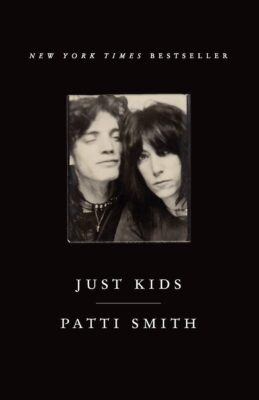

I had hardly ever listened to Patti Smith’s music before picking up this book, and I hardly ever read memoirs, because I find most of them self-indulgent and boring, sorry, memoirists! But this one was recommended to me as a memoir that was “worth it” and it was available from the library. Good news: it was totally worth it! Even if you, like me, are only passingly aware of Patti Smith and Robert Mapplethorp’s body of work! Smith’s prose is plainspoken and authentic, which makes it extremely readable. I have been thinking about why I enjoyed this book so much and I think there are two big reasons, besides the good prose and the authenticity:

I had hardly ever listened to Patti Smith’s music before picking up this book, and I hardly ever read memoirs, because I find most of them self-indulgent and boring, sorry, memoirists! But this one was recommended to me as a memoir that was “worth it” and it was available from the library. Good news: it was totally worth it! Even if you, like me, are only passingly aware of Patti Smith and Robert Mapplethorp’s body of work! Smith’s prose is plainspoken and authentic, which makes it extremely readable. I have been thinking about why I enjoyed this book so much and I think there are two big reasons, besides the good prose and the authenticity:

1. The micro: Smith must have been a diligent journal-keeper, or have a memory far better than mine, because the picture she paints of her youth, and of 1970s New York, is filled with beautiful little glimpses of a world that no longer exists: the small, cheap meals that she bought regularly at the corner café; descriptions of miniscule New York apartments and cheap but meaningful trinkets; the cast of characters at and around the Chelsea Hotel and their various signature attire or speech patterns; the cost of a bus ride or a cup of coffee; her favorite dress or hat; even their day-to-day decision-making processes as young, poor artists in a New York that seemed willing to let them do anything. By the end of the book you can already feel the era slipping away, thanks to her inclusion of these personal and sometimes surprisingly small details.

2. The macro: The thing that really clings about this book is how Smith and Mapplethorp existed in the world in an entirely different way, almost unrecognizable when compared to my experience. Obviously, part of this is that I do not live in 1970s New York. Most of this, however, is due to the fact that throughout the narrative, Patti and Robert’s very identities as artists is impossible to subsume into anything trite or expected. Sometimes their artist natures drive the narrative, because their need to create leads to monumental life decisions, like moving to New York, or what media to use, or who to hang out with. But it’s bigger than that. Throughout the book Smith talks about her poetry and the literature and music that filled her days and her thoughts; how Patti and Robert talk about their art is abstract and deep and although I understood the words on the page, on a deeper level I knew that I wasn’t really understanding the currents passing between them. At one point, Smith decides to go to Paris to visit the home of her hero Rimbaud. This is almost a cliché, right? Young poor artist searches for meaning and inspiration in Paris. But in her telling, you see that this choice, and her art, is almost not a decision; it’s a calling, a force, it’s meaning. It’s art. Similarly, she and Robert incorporated their Catholic upbringing into their art in a way that almost feels foreign to me, a person raised with a slightly more ham-handed version of religious imagery, per 1990s American evangelical style. In other words, this book did what I think the best memoirs can do: show you what it’s like, for a very fleeting moment, to be someone else.

I listened to Smith’s albums for several hours after finishing this book, and while I don’t love it all, there were certain songs that resonated, and I appreciated them more because of reading the book. This would be a great book club discussion book, and I’ve already recommended it to several friends who I think would enjoy the glimpse into 1970s artist New York.