Another (daft) reading challenge! A few years back I took the best part of 8 months to read through an Indonesian translation of The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer (Kanker Biografi Suatu Penyakit.) I wasn’t sure if I was going to continue with the rest of the translations of Mukherjee’s books. But Google Play was nothing but persistent.

So there we have it; it was a little less laborious this time, but I have managed to make my way though the translation of Gene: an Intimate History. Or Gen: Perjalanan Menuju Pusat Kehidupan (Which is literally ‘Gene: A Journey to the Center of Life.’ Not a bad shift in title.)

Like his previous book, Gene is very ambitious: it is a history of the field of human genetics, from Mendel to CRISPR. This is a very broad field, and Mukherjee makes it clear from the start that this is a history of how we understand our genes in a medical related context. Plants, for example, are of course mentioned in regards to Mendel, and then that’s it. As a consequence, there is no discussion of GMO technologies, which are still a big deal. There is also very little information about genes in the context of human evolution here—so the inmate history of our species is not explored. Instead the focus is more clinical—and ethical.

However the topics that are focused on here are very broad, and Mukherjee does his best to organize the topics both chronologically and thematically. There is a lot of focus on big names and big events, especially later in the book when biotechnology comes to the fore. But I have always appreciated though—both in this read-through and the last—is the focus on the historical and social context.

This, of course, means that a significant number of pages are dedicated to the rise of eugenics, which starts very early on in the field’s history. It’s Francis Galton, a cousin of Charles Darwin, who is seen here as the pioneer in the 19th century. But the progress of the idea is followed through the next century; as expected, the author covers the infamous Buck case in the US and the “racial hygiene” laws of Nazi Germany. However, he also details the fundamental similarities Lysenkoism had with the Third Reich: they both used genetics to construct a version of humanity and identity that could be used twisted to promote certain political ideals. He also points out the the greatest example of negative genetics in recent history may actually lay at the feet of the countries where sex selection took off, leading to the loss of so many female children.

So where does the intimacy implied in the original English title come from? In part it comes from the history of the author’s own family. An uncle and two of his cousins suffered from debilitating schizophrenia. The fact that their illness is likely hereditary hangs like a shadow over the family. There is also his personal relationship with Paul Berg, who was a leader in recombination DNA technology. There would be no transgenics without his work. Much like in his first book, Mukherjee brings a lot of gentle empathy into his writing when describing patients. One particularly standout section covers the work of Nancy Wexler, who dedicated herself to the study of Huntington’s disease after her mother was diagnosed.

Even in translation, the book was a joy to read. It is, in most part, a fairly even handed account of a number of major events in the history of genetics. Sure, there were a number of places I thought the narrative had been a little too simplified and rendered a little too linear, but this all ties back to what I mentioned earlier about what topics were chosen for greater focus and what was best left by the wayside.

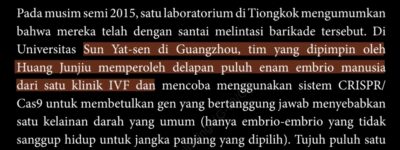

Even though it’s about a decade old now, this is still an important book, especially in the current political environment. Near the end of the book, I jumped on the one mention Mukherjee makes of a lab in China has started using CRISPR to edit human embryos [Translation in alt-text]:

He then mentions at the end of the section that there was some fear that this kind of editing might become a bit of an intercontinental arms race. I will be reviewing a book or two about the man who tried to ‘win’ that arms race very shortly, I promise.

Concerning my reading of this translation? It was a little faster than last time! But some sections of the book were harder than others; for example, the sections about the struggles his family had with his cousins and uncle did use more complex language. Which I found a little harder to navigate.

For cbr17bingo, this is G. For Gen/Gene. Very fitting.