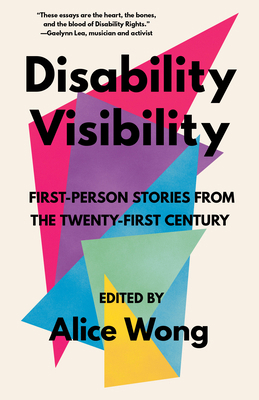

Why did I read Disability Visibility: First-Person Stories from the 21st Century from Alice Wong and dozens others? I urgently needed to borrow a book from a friend for specific and convoluted reasons. And the Storygraph’s Genre Challenge includes “an essay collection by a disabled author.” Finally, as a person who digs fashion and human rights, I was (and am) a fan of well dressed activist Alice Wong. Essentially, I had no reason not to read it.

The book is split into four groups of essays – being, becoming, doing, connecting. Each group has a little less than 100 pages of bite sized essays, described as “A groundbreaking collection of first-person writing on the joys and challenges of the modern disability experience: Disability Visibility brings together the voices of activists, authors, lawyers, politicians, artists, and everyday people whose daily lives are, in the words of playwright Neil Marcus, ” ‘an art . . . an ingenious way to live.’ ” Someone might be able to say it better, but not me.

It starts off hard to read with an argument from a very pleasant animal rights activist arguing for “post birth abortion” for disabled babies (you can figure out this man’s priorities). But then it gets easier. Then harder. It’s never too much. Anthologies of any kind usually overwhelm me and I need to take breaks between the items in the collection. But I read dozens of essays within two days. The pacing and grouping is just damn good.

I wouldn’t say it’s inspiring, partially (but not entirely) because of inspiration porn – which was mentioned. But I would say it’s reassuring that these people exist and are doing what they do.

Within the essays, there was enough variety to show that the surface of living with a disability wasn’t even scratched, which I think was the point. Some people went into graphic detail about their disability, others didn’t even mention what theirs was. People were told their autism was from heavy metals (something I’ve heard and didn’t know was actually a thing). They wrote about fashion and being simultaneously infantilized and geriatrized.

The book says it is about the everyday people, although most or all the contributors seem to stick out a bit. That isn’t a criticism because they wouldn’t have gotten in the book otherwise. And like I said, it tells you just enough to know that there’s a lot more.