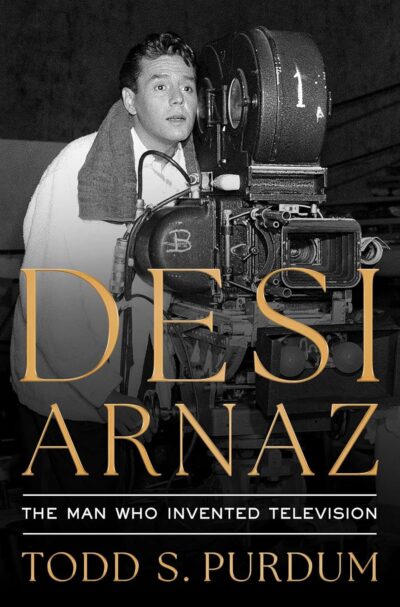

The subtitle of Todd S. Purdum’s biography of Desi Arnaz makes a bold claim: that he “invented television.” Of course, Purdum does not mean it literally, but with the iconic sitcom I Love Lucy, Arnaz and his wife Lucille Ball established so many of the practices that became industry standards. While Lucille Ball’s masterful comedic performance may be what is best remembered, Arnaz’s part in the show’s success was not at all secondary.

But first, there’s Cuba. Purdum takes the reader to the city of Santiago, where Desi’s father (also Desi) was a prosperous pharmacist and later the mayor. The Arnazes lived in splendor until the political tides turned against Mayor Arnaz, and the family had to split for Miami, Florida. (Interestingly, Miami was not yet an established enclave for Cuban emigres, according to Purdum.) Where Desi had dreamed of coming to America for college and possibly law school, he now came in relative squalor, forced to work and live in a warehouse with his deposed father.

Music became his way back to the top. Though not an extraordinarily talented singer or musician, he had charisma and star power to spare. He impressed Xavier Cugat and, when the pay as a band member was too low, started a band of his own, helping to popularize the Conga in the U.S. He got a big part on Broadway, played the role in the film adaptation, and thought a film career was an inevitability. But leading roles for Latin American actors were few and far between. And then he met Lucille Ball, who was also struggling to hang on to a film career.

I Love Lucy necessarily takes up the bulk of Purdum’s account. It is both the biggest success, by far, of Desi’s life, and the vehicle through which he made his greatest contributions to the medium of television. For instance, I Love Lucy was shot on film because Desi insisted it would look better. Prior to that, shows had been transmitted live within reach of the broadcast network and recorded on a kinescope to be sent to the rest of the country and televised a week later. Almost instantly, film became the industry standard.

Desi also came up with the three-camera format for shooting sitcoms, which allowed the crew to film scenes from multiple angles without having to do retakes. This had seemed like an impossible thing to do while filming in front of live audience, but Arnaz and his cinematographer Karl Freund got it done, and eventually everyone else copied the format.

Offscreen, Desi’s life makes for more depressing reading. Believing in a dated and absurd idea of machismo, he refused to be faithful to Ball, where also being insanely any time he so much as suspected her of being interested in other men. Though he had brilliant success as the president of Desilu Productions, including the tv series The Untouchables, the pressure of running a big company got to him. Arnaz drank heavily, and it made him temperamental and difficulty to work for. It also lead to the dissolution of his marriage to Ball.

Purdum does a good job balancing his account of Arnaz’s life, paying respect to his tremendous successes and crediting him properly for his innovations while laying bare his flaws and shortcomings. Readers with a keen interest in the history of television will get a lot out of this book, whether or not they love Lucy.