“In answer to those who claim young people protesting across the country against mass incarceration, police violence, deportation, school inequality, rising Islamophobia, global injustice, and environmental racism are nothing like the activists of the storied days of the civil rights movement, our historically informed answer must be, they are” (208).

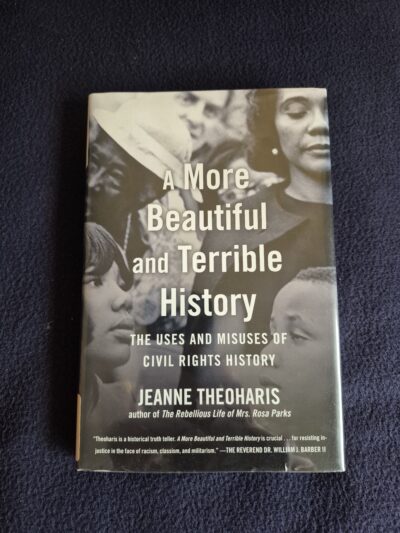

Jeanne Theoharis’ A More Beautiful and Terrible History: The Uses and Misuses of Civil Rights History has been languishing on my TBR since 2018, the year it was published. I wish I had read it earlier, but I do think its message is useful in 2025, when we are facing unprecedented awfulness and rollbacks of civil rights.

This slim volume–just over 200 pages not counting the extensive endnotes that Theoharis includes to document her research–takes as its main premise that the civil rights movement of the early 20th century has become mythologized to such an extent that its leaders have become two-dimensional cardboard cutouts of American heroes and that the struggles and successes of the movement have been flattened into a simple narrative. Rosa Parks stayed seated on the bus; white Southerners brutalized civil rights protesters; Martin Luther King Jr. spoke of his dream in Washington DC: the tidy narrative of this chapter of American history. Theoharis illustrates that this simplification of the civil rights movement ignores and obfuscates the realities of just what the activists were facing in many different and dangerous ways.

To start, The North/South binary sanitizes the amount of racism in the North, evidenced by conscious efforts to segregate public life for black and white citizens; Theoharis recounts oft-ignored stories of conscious segregation, or as city leaders called it, “separation,” in NYC, Boston, Detroit, Chicago, and Los Angeles, to explode this binary that allows us to see the North as “good,” “enlightened,” not racist versus the South and its red-faced racist rednecks. She tells the stories of the civil rights struggles in these cities that used de facto segregation to harm its POC populations (often with the cooperation of media organizations like the New York Times–I’m sure I’m not the only one who hears echoes of this complicity in contemporary media).

Theoharis also explains that many of our civil rights figures have been flattened into saintly figures; MLK notably was hated by much of white Americans, the majority of whom felt that POC were asking for too much and moving too quickly. (Again, echoes of the anti-DEI movement and its willful misunderstanding of what DEI efforts actually mean.) This flattening ignores the collective energy of the youthful activists who actually initiated the first boycotts, and it also obscures the contributions of the movement’s women. Rosa Parks was a committed activist who didn’t simply refuse to get up from her seat because she was tired; both before and after her arrest, she was tagged as anti-American and potentially Communist for her advocacy against poverty and segregation. Far from being just her husband’s helpmate, Coretta Scott King pushed Martin Luther King toward more radical positions on racial justice and economic inequality. And those are just the well-known names; Theoharis details several women in both the North and the South who risked their lives and reputations to protest against the inequities that they lived.

My only issue with this book is its structure. I prefer a more linear chronological organization. But that is a minor quibble for such a short and powerful book. It reminds me that the fight against injustice is long and hard, but collective action works.