Brothers Peter (32) and Ivan (22) could not be more different. Peter is a successful human rights lawyer and university lecturer, attractive, a social butterfly. Ivan, on the other hand, is an underemployed, underachieving chess player. He’s awkward and while he’s not ugly, his second-hand clothing (a deliberate choice made for ethical, not financial reasons) and braces make him a far cry from his more glamorous brother. They are both still grieving from the death of their father from cancer, a few months prior. Instead of bringing them together, their father’s death seems to have pushed them even further apart.

Brothers Peter (32) and Ivan (22) could not be more different. Peter is a successful human rights lawyer and university lecturer, attractive, a social butterfly. Ivan, on the other hand, is an underemployed, underachieving chess player. He’s awkward and while he’s not ugly, his second-hand clothing (a deliberate choice made for ethical, not financial reasons) and braces make him a far cry from his more glamorous brother. They are both still grieving from the death of their father from cancer, a few months prior. Instead of bringing them together, their father’s death seems to have pushed them even further apart.

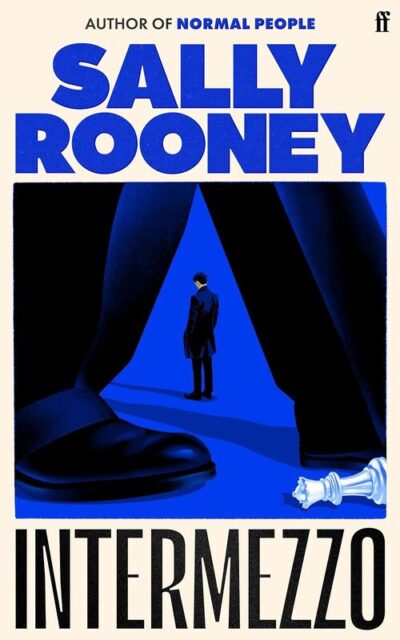

The funny thing about Rooney’s earlier, breakout hit Normal People is that if you ask people if they liked it, they will either declare their undying love for Connell and Marianne, or they will eviscerate the book. There doesn’t really seem to be much in between. I suspect the same is true for Intermezzo. Fortunately, I loved Normal People. I thought it was a rich, critical but nuanced portrayal of an oft-misunderstood generation. Intermezzo does the same thing, except that it’s deeper and richer still. It’s a whip-smart book where the author is like a loving mother: she adores her characters, but she doesn’t spare them their faults and flaws.

I suspect that most of the detractors of this novel dislike, or at least find it hard to emphatise, with the characters. I understand why that is. Ivan is socially awkward, Peter is prone to bouts of self-pity, and neither of them seems to have much respect for the other. Peter thinks Ivan is an embarrassment, with his socially awkward dialogue, his nerdy hobby and his ill-fitting clothes. Ivan thinks Peter is a domineering hypocrite who lambasts him for having a much older girlfriend while dating a much younger woman himself. The truth is that Ivan isn’t as socially unaware as Peter thinks he is, and Peter isn’t as judgemental as Ivan thinks he is. Peter does look out for his brother, at the detriment to himself occasionally.

Large swaths of the books are also given over to the brothers’ relationships. Ivan, in the first few pages, meets Margaret, a thirty-six year old woman separated from her alcoholic husband. Margaret finds Ivan’s awkwardness endearing and sincere, and refreshing. Peter, meanwhile, is in a semi-platonic relationship with fellow lecturer Sylvia. She is the love of his life, but due to an accident she is in a great deal of pain and cannot have (traditional) sex with her partners, which has led her to break up with Peter; she doesn’t want to trap him in a relationship that’s missing a key component. They are, however, still close, and neither one is able to let the other one go completely. There’s also Naomi, a student and possibly part-time sex worker. Peter gives her cash sometimes; she sells him drugs. He is deeply infatuated with her, and doesn’t understand why. For the life of him, cannot choose – though neither woman is asking him to – and the relationships weigh heavy on him, so much that he thinks about ending his life.

In fact, Peter’s story is both ridiculously self-involved (he feels VERY sorry for himself) and endearing; it’s not the relationships that weigh on him, it’s his father’s death and the sense of responsibility he feels for his brother, whom he doesn’t understand and cannot seem to build a relationship with. His mental wellbeing suffers, and as a consequence he obsesses. Long, meandering sections of the book are written in a stream-of-consciousness style, especially from Peter’s point of view. It doesn’t make for an easy read but it works well to illustrate his jaded state of mind; Peter is excellent at putting up a façade for his friends and coworkers to hide the fact that he is in a constant state of deep, existential panic.

In other words, it’s easy to judge Peter for being a spoiled brat who whines about his relationship issues, but depression doesn’t work like that. It’s a testament to Rooney’s skill that she requires you to take the characters seriously while at the same making fun of them; the book is frequently hilarious. It’s also remarkably steamy for such a literary work, though Rooney avoids the cringe factor a lot more than most of her male counterparts (a low bar, but still).

I get why people wouldn’t like this book. The narrative takes time to get used to, and I can see why some readers would find it hard to sympathise with the characters. Ultimately, though, this is an observant and intelligent novel that deserves all the credit it can get.