If you’re a baseball fan who also happened to be on Twitter in the pre-Elon days, the name Old Hoss Radbourn will probably be familiar to you via the brilliant parody twitter account pretending to be the great pitcher of old, humorously carping about the national pastime and how much easier contemporary players had it.

The Old Hoss was, in fact, a real ballplayer named Charles Radbourn (or Radbourne, depending on the source.) He’s in the Hall of Fame, having won over three hundred games as a starting pitcher in the 19th century. He pitched for several teams, but his greatest legacy is the season he had in 1884, when he was the ace of the pennant-winning Providence Grays. (Yes, there was a major league baseball team in Providence, Rhode Island.) That year, Radbourn set the record for most wins in a season by a pitcher, with an impossible 59. Remarkably, the season was much shorter then than it is now, at only 112 games.

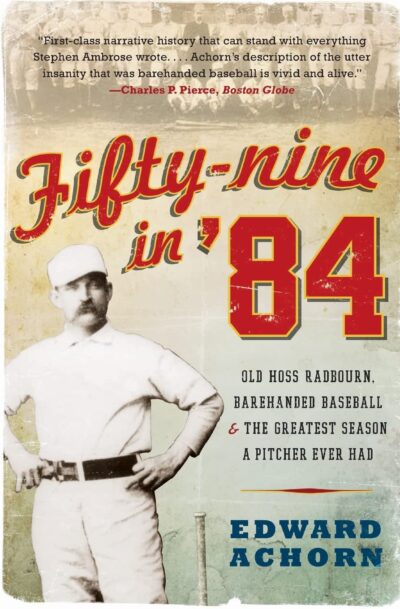

So how did Radbourn do it? As Edward Achorn recounts in “Fifty-Nine in ’84”, it wasn’t easy. Baseball was a far different game in those days: fielders played without gloves, foul balls didn’t count as strikes, and teams usually only carried 11 or 12 players total. That meant that there were really only two or three pitchers on a team, and they often had to play another position on the days they weren’t pitching. Radbourn’s Providence Squad started the year with the best pitching in the game, with Radbourn the established veteran and a young, hotheaded rookie named Charlie Sweeney backing him up. Sweeney racked up victories and strikeouts like few other hurlers in the game’s history, but Achorn’s book recounts his precipitous fall due to drinking and a foul temper.

Sweeney’s implosion led directly to Radbourn’s bid for eternity. Impossible as it may seem to fans of today’s fame, the Grays essentially let Radbourn pitch practically every game for two months as they tried to lock down the pennant. Pitching day after day, putting tremendous strain on his arm, Radbourne still managed to put up incredible numbers.

It’s a crazy story, no doubt, but it’s impact is a little blunted by Achorn’s telling. Achorn has clearly done a ton of research for this book, but he makes the mistake of putting seemingly all of it in, leading to dozens of passages that are little more than irrelevant asides. For a book meant to focus on Radbourn, the author is only too eager to relay any anecdote he encountered that interests him, even if it’s about a player on another team, a teammate’s father, the mayor of Providence, or the ancestry of Radbourn’s sweetheart, a local boardinghouse owner and possible former sex worker. These digressions vary in entertainment value, but taken as a whole they overwhelm the reader with details. While some context on the world of 19th-century America and the game of baseball is necessary, Achorn should have been more discerning.

Still, for readers who are passionate about the history of the National Pastime, Fifty-Nine in ’84 has enough to make it worthy of the starting lineup, even if it’s not quite worthy of the Hall of Fame.