I feel like I am the odd one out because I didn’t like this one as much as the previous one. Not sure if I had certain expectations for this novel and the fact that Bennett took a different approach colored my reaction or if it was something else entirely. It’s also why it’s taken me 2 months to even want to try to tackle this review.

I feel like I am the odd one out because I didn’t like this one as much as the previous one. Not sure if I had certain expectations for this novel and the fact that Bennett took a different approach colored my reaction or if it was something else entirely. It’s also why it’s taken me 2 months to even want to try to tackle this review.

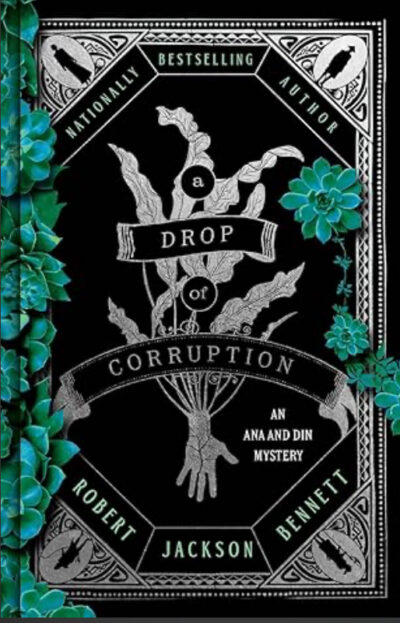

I wonder how much this is the novel he had originally intended to write when he started his first novel and introduced us to the empire of this world, and how much changed because he realized he needed/wanted to make a statement against autocracy and monarchy given today’s current political environment. What do I mean by this? In the first novel, Robert Jackson Bennett sets up this large empire that also seems slightly nefarious. Something about the increased threat of leviathans made it feel like this powerful empire was in a precarious position, and being fantasy, one of course wonders if there is some deeper reasoning, some dark pay off the empire has made that is now resulting in increased threats. How much did going against some natural order lead to the current predicaments and looming threat?

In this novel, we don’t explore that part too much further (we definitely explore bad actors within empire but not the empire itself as the evil), and instead we are in a part of the Empire that has a long standing contract/treaty with a formerly independent kingdom. The end of the original treaty is approaching and there are questions and tensions on all sides: some locals look forward to the treaty ending and their great king being back in charge; others prefer the freedom the empire represents, having escaped positions of slavery where their lives meant nothing and found purpose in work for the empire. Ana, our narrator’s supervisor, very decidedly comes down against autocracy and the monarchy, and explainso to Din how it has led to hoarding of wealth at the top, oppression of the common people, and stagnation against progress (even while Din remarks on some of the remarkable achievements whose knowledge the kings hoarded). All very valid and interesting interpretations but since I was prepared for the empire as an example of the evils of colonialism which imposed their culture on others, I guess the empire being the lesser evil threw me for a loop (not sure why I kept thinking of Great Britain and Hong-Kong here – I mean I do high level because it’s the most prominent real life example I could think of featuring a long term treaty but I don’t know enough about the details of all of that to understand if it’s more than a situational comparison).

This novel takes places a period of time after the last novel so Ana and Dinios Kol have been working together and have had time to adjust to each other. After how successful Din was in the last novel, I was surprised (and disappointed) that instead of well-functioning partnership, Din is actually pretty over his job, occasionally feels pretty checked out (there were a few instances where he seemed surprised by a point Ana was trying to prove and he should have understood much sooner because he isn’t a dumb character) and wants to do something else.

The mystery itself was pretty solid and interesting. There was a throw away line/fact mentioned early on and repeated a few times in the novel so I guessed pretty early on what at least one key part of the resolution would be – I think it was subtle so not a surprise that I got there before even Ana but it all just kind of combined to make me enjoy this one slightly less than the previous novel – even while appreciating Robert Jackson Bennett’s detailed explanation in the afterword, and the message he chose to drive home in this novel.

From the afterword:

In the decade or so before this inflection point, however, the story was very different. There was a dreadful murmuring around the globe suggesting that autocracy was not merely surging, but better: more efficient and effective than liberal democracies could ever hope to be. “Wouldn’t it be better,” some began to mutter, “if we had someone in charge who didn’t have to listen to so many useless little people?”

And it is a curious correlation that, during this moment of self-doubt, fantasy’s fixation with autocracy not only grew in intensity, but grew stranger. For it was then that we saw fewer stories invoking a traditional, romanticized ideal of divine rule wielded by beneficent patriarchs, and in their place came a wave of fantasy that embraced if not celebrated the capricious cruelties of autocratic regimes.