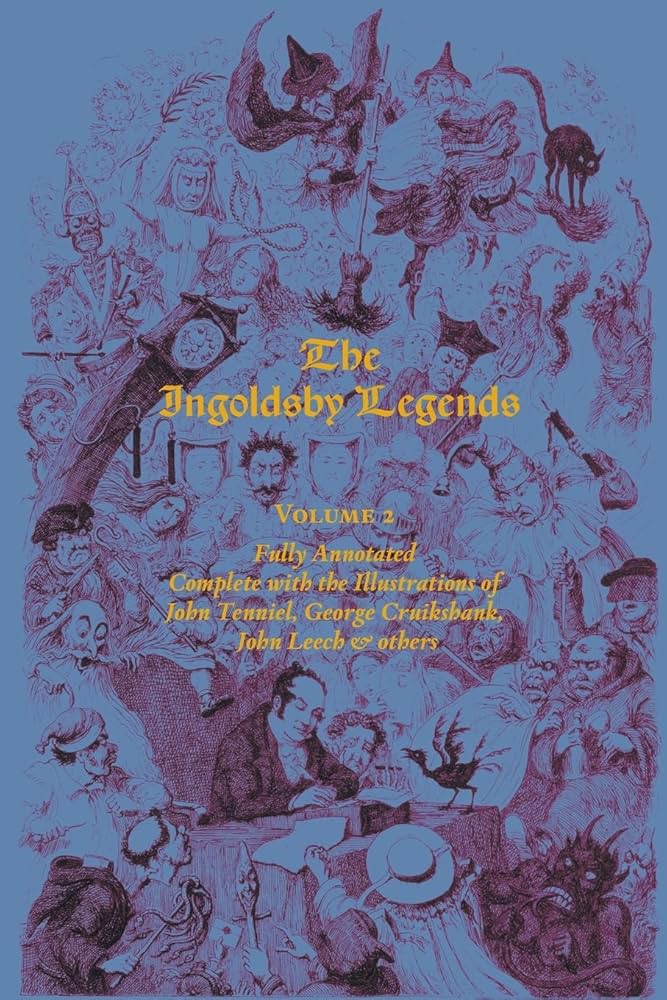

Thomas Ingoldsby was the alias of Richard Harris Barham, a Cleric for the Church of England. In between his sermons (he at one time had a minor canonry at St. Paul’s Cathedral), Barham collected Kentish folklore, which he transcribed as pastiches as “The Ingoldsby Legends” in Bentley’s Miscellany, an English magazine edited by Charles Dickens. Most of the stories are written in prose, poking fun at famous plays, books, and people of the day, and were illustrated by various artists such as George Cruikshank (a known caricaturist), John Leech (of Punch magazine), John Tenniel (of Alice in Wonderland fame) and Arthur Rackham (one of the leading fairy tale illustrators, and a personal favorite). They are rife with sayings that are still in use to this day, as well as several ideas that are very familiar if you’ve ever read Good Omens. I do love when your reading material turns out to be some giant, interconnected web.

I became interested in these books because it was mentioned in Sarah Rayne’s Property of a Lady, which is a rather creepy England-based horror book. It mentioned Ingoldsby as a source for one of the tales about “the Hand of Glory” (which Cassandra Clare also alludes to in Lady Midnight), a light made of a dismembered murderer’s hand. You know, the healthy and wholesome stuff everyone loves to read about!

Luckily not every story has to deal with things like that, though the stories do abound with ghosts, deals with the Devil (the most long-suffering and tragic figure in the volumes), poking fun at religious figures, and the perils of romance.

Everything you need to know about the author is that he opens the collection with the sentence:

“The World, according to the best geographers, is divided into Europe, Asia, Africa, America and Romney Marsh

Sarcasm is very prevalent in these books; as is an irreverence for religion. Being Anglican, Barham saved most of his severest scorn, vitriol and sarcasm for Roman Catholicism. Though thanks to him I did learn about St. Rumbold of Buckingham, who was believed to have been born in 662 and died on the third day after his birth, expressing Christian faith, requesting baptism, and even delivering a sermon before his death (industrious baby, he was.)

I will ding for the Antisemitism and Sexism, but they were unfortunately common in the 1800’s when this collection was published. For example, the parody of Merchant of Venice is probably even more antisemitic than the play, and in a lot of the stories women are described as being one of (if not a combination of) three things: dumb victim, shrew and/or unfaithful sex-obsessed devil-worshipping social climber. Also slightly offensive (but due to the period, not surprising) is that the Devil is described as being Black; what is surprising is that he is often described as wearing shoes over his hooves. I can only imagine what that would look like. I will also note that the glossary at the bottom of the pages got a little repetitive after awhile, as did the fact that it explained a lot of things I thought were rather common knowledge. I appreciated that the Introduction admits that in most of the information available on Barham was been severely whitewashed by his son.

If you like Folklore, Fairy Tales, Witty Sarcasm, and Good Old-Fashioned English Snark, read these.