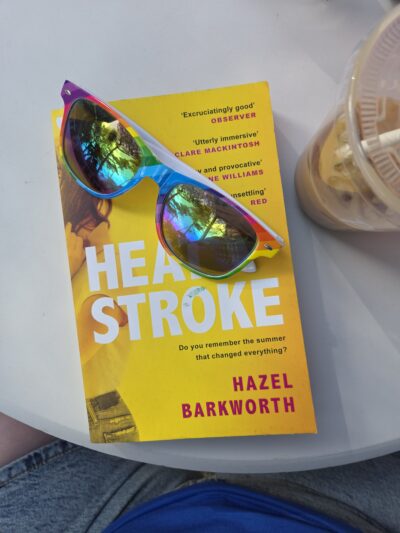

Heatstroke (2020) is clever–cleverer than its cover, certainly cleverer than its title. I remember that the review blurbs on the covers of Gillian Flynn’s Sharp Objects (2006) and Megan Abbott’s Dare Me (2012) signposted how terrifying teenaged girls can be–and this is certainly a thing, the way teenage girls are inscribed with contradictions of power and anxiety, and Heatstroke does deal with that–but I remember thinking, well, it’s actually the mother that is fairly fucking monstrous in Sharp Objects, and parental figures are pretty absent in Dare Me, so terrifying teenaged girl doesn’t emerge out of a vacuum, she comes out of boredom and claustrophobia and loneliness and constant being-looked-at-ness and the deep-seated unconscious conviction that the time she has left to be fully and wildly herself is fading faster and faster, like the stars on a midsummer night.

Heatstroke (2020) is clever–cleverer than its cover, certainly cleverer than its title. I remember that the review blurbs on the covers of Gillian Flynn’s Sharp Objects (2006) and Megan Abbott’s Dare Me (2012) signposted how terrifying teenaged girls can be–and this is certainly a thing, the way teenage girls are inscribed with contradictions of power and anxiety, and Heatstroke does deal with that–but I remember thinking, well, it’s actually the mother that is fairly fucking monstrous in Sharp Objects, and parental figures are pretty absent in Dare Me, so terrifying teenaged girl doesn’t emerge out of a vacuum, she comes out of boredom and claustrophobia and loneliness and constant being-looked-at-ness and the deep-seated unconscious conviction that the time she has left to be fully and wildly herself is fading faster and faster, like the stars on a midsummer night.

And this power and anxiety is what Rachel, the POV character, is wary of when it comes to her own fifteen-year-old daughter Mia and her seemingly tight-knit circle of girlfriends, but nostalgic for when it comes to herself. Rachel misses being wild and unpredictable and singing on stage with her indie band in 1994; she misses the fear of getting caught, or caught out–now her body language, and her conversation, is precisely choreographed and tailored for her audiences of mums at her book group, and colleagues and pupils at the secondary school (junior high?) where she works, and her life is bordered by suburban lawns and the husband she only sees on Skype as he works in America and the demands of her beloved daughter for catering and rides and support. Indeed, the thing about domestic/suburban noir is that it’s about performance and what happens when the show can’t go on, and Barkworth understands this beautifully:

As she walked down the corridor to her classroom, Rachel had to summon the swagger that usually came so easily. She forced her back to hold straight, her shoulders to sit low. She made the heels of her sandals click evenly as she strode. She managed to clear a gaggle of squawking Year 7 girls with no more than the raise of an eyebrow. She usually felt invincible in school. That day she had to force it, to mimic herself. (p. 123)

The fact that Rachel’s walk down the hall is a performance that can consciously be imitated without anyone realising its fakeness suggests that the initial performance was just that, a performance, not an authentic way of being in the world (although what is? even Rachel’s moments of liberation are scripted).

The central crisis here is that one of Mia’s BFFs, Lily, never shows up for the sleepover with Mia, and is eventually reported missing–and it soon becomes clear that she has not left alone, and that she took her mother’s lingerie with her. As Lily is a minor (the age of consent in England is 16), she could not have legally consented to any sort of lingerie-requiring activity, but this still becomes sordid tabloid spectacle, and a moral panic, as well as revealing fissures in the seemingly close relationship between Mia and Rachel–and yet, the narrative is tricky enough that for a long time we don’t quite know what the full implications of all of this are. I don’t want to go into more detail about how it’s tricky, and how it engages with expectations, in order to avoid spoilers, but it is an uncomfortable, if gripping, read at times.

It’s also suburban England, and an early heatwave–and the English tend to be as unprepared for heat as they are for snow, which doesn’t help with anything.

I really enjoyed this–again, as with my other reviews so far this year, I would have liked a more bitter ending (maybe it’s me, hi, I’m the problem, it’s me), and I’m not sure all the narrative tricks are fully necessary–there’s a hint of debut author over-enthusiasm at times. But I’ll definitely pick up her next book soon.

Title from Soundgarden’s Black Hole Sun (1994); if you know the video you know.