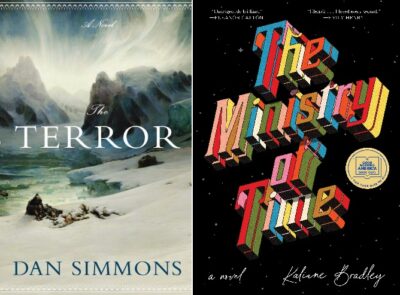

Life has an odd way of making things come together sometimes. Either that, or I simply wasn’t paying attention when I ended up accidentally reading two books about the lost Franklin expedition at the same time. Both books are fiction, which means that they take their own liberties with the truth; after all, not much is known about the exact fate of the men aboard the HMS Terror and the HMS Erebus.

Life has an odd way of making things come together sometimes. Either that, or I simply wasn’t paying attention when I ended up accidentally reading two books about the lost Franklin expedition at the same time. Both books are fiction, which means that they take their own liberties with the truth; after all, not much is known about the exact fate of the men aboard the HMS Terror and the HMS Erebus.

What we do know is this: explorer Sir John Franklin, experienced but not particularly successful or talented, was picked more or less by default to lead an expedition into the Arctic in the hopes of finding the fabled northwest passage. The ships he took were the pride of the Royal Navy. They even had engines (unheard of at the time) and reinforced hulls able to withstand the awesome pressure of the pack ice. Unfortunately, the expedition was beset by bad luck as well as troubles of their (or rather, the navy’s) own making. The cans of food – a novelty technique – had been bought from the cheapest bidder and the very deadly but little understood botulism that follows from poor technique killed a fair number of men, and led the rest to starve. Further bad luck came in the shape of unseasonably cold summers that meant the ships remained stuck in the ice, and the men were forced to abandon ships. Local Inuit populations have it that some of the men made it hundreds of miles away from the ship before perishing of starvation, disease and cold. Fragments of their lives and human remains were found a decade or so later, bearing knife marks on bones that suggest they were forced to resort to cannibalism in their last moments. Not a story the Royal Navy is particularly proud of, and it was swept under the rug.

Dan Simmons’ The Terror focuses on the time the men spend on the ship and on the ice, as they fight for survival. We see the story both through the eyes of several characters, both through logs, letters and diary entries as well as through narration, though most of the narrative comes from Francis Crozier, a Catholic Irishman – and therefore an outsider, barely accepted by his peers – who captains the HMS Terror. Crozier is a down to earth kind of guy, and the increasing desperation he feels as he remains stoic and calm in the face of trouble is almost heartbreaking.

Dan Simmons is a horror writer originally, and my biggest issue with this book is that he feels the need to force some sort of monster into the narrative when it hardly needs it. Fortunately, the monster takes a backseat to everything else that’s going on. The plight of the men is already terrifying; the long nights exposed to the elements don’t need jumpscares. By far the scariest bits of the book come from the men describing the effects of scurvy as they grow weaker and weaker, and reading about the decisions as to whether to starve or eat the spoiled food. Their clothes are covered in blood because they bleed from their hair follicles. Their teeth fall out. They lose fingers and toes to frostbite. They are always cold because they have long since run out of coal, and the sweat in their clothes and sleeping bags won’t dry. Just when you think it can’t get any worse, it does.

Something else that struck me as odd is that a female character in the shape of an Inuit woman, known as Lady Silence for her lack of tongue, is added to the plot. For the first 90% of the book, she barely has any function and her presence is mostly of the Breasing Boobily Redux: the Exotic-Erotic other. I’m serious; Simmons spends a lot of time describing her breasts. And yes, I get it, sailors get lonely, but it’s a little ridiculous. If you can’t write women well, then why include them when you have the perfect excuse not to? Then again, Lady Silence is a powerhouse in her own way and I thought the ending was oddly touching, so make of that what you will.

I listened to the audiobook (all 28 hours and 28 minutes of it; it’s over 900 pages in print), which isn’t my usual preference. In this case it meant that I mostly listened for an hour or so every week when I was doing my cleaning round, which in turn meant that I had a little trouble telling the characters apart. There are a lot of names. I also wasn’t very fond of the narrator, who felt the need to give almost every character who isn’t Crozier a weirdly reedy and oddly lilting voice. Crozier, who by all accounts was an accomplished scientist and very intelligent man in real life, is almost reduced to a gruff sailor. If I were to do this again I would just read the book rather than listen to it, so I’m choosing not to include that part in my review. In book form, I bet it’s excellent, well researched and detailed without losing the pace.

The other book I read about a related subject is Kaliane Bradley’s The Ministry of Time. We meet our nameless narrator (co-incidentally, also the second book I’ve read this week where the main character remains anonymous), a young woman who works for a mysterious department, an obscure bureaucratic government office that doesn’t really seem to connect with anything else. She is meant to act as a bridge between the modern world and a group of expats, as they are called: immigrants not from a different place, but a different time. Among their group are Arthur, taken from the Battle of the Somme in 1916; Margaret, from plague-riddled 17th century London; and Graham, to whom our main character acts as a guide.

Graham is Graham Gore, not a fictional character but an actual person who died of unknown causes during the Franklin expedition. The one picture we have of him shows a striking man with dark, curly hair and a piercing gaze, handsome if not necessarily beautiful. The main character shares a house with him, teaches him how to navigate the world around him. Some things come easy to him; Graham was an active man in his previous life and he loves cycling and motorbikes, and takes a liking to Asian cooking. Other things cause him more trouble. He can’t get the hang of modern music until he discovers Motown. Modern concepts of love, sex and dating baffle him. Worse are his total ignorance of the history between the year of his purported death, 1848, and the current day. He suffers from survivor’s guilt when he learns of the fate of the expedition; though the choice to leave wasn’t his, he feels like he abandoned his men. Learning about the Holocaust nearly sends him over the edge.

Graham is Graham Gore, not a fictional character but an actual person who died of unknown causes during the Franklin expedition. The one picture we have of him shows a striking man with dark, curly hair and a piercing gaze, handsome if not necessarily beautiful. The main character shares a house with him, teaches him how to navigate the world around him. Some things come easy to him; Graham was an active man in his previous life and he loves cycling and motorbikes, and takes a liking to Asian cooking. Other things cause him more trouble. He can’t get the hang of modern music until he discovers Motown. Modern concepts of love, sex and dating baffle him. Worse are his total ignorance of the history between the year of his purported death, 1848, and the current day. He suffers from survivor’s guilt when he learns of the fate of the expedition; though the choice to leave wasn’t his, he feels like he abandoned his men. Learning about the Holocaust nearly sends him over the edge.

The novel is a hodgepodge of romance, historical fiction, science fiction and spy thriller. There are mysterious shenanigans at the ministry; people randomly disappear. In all honesty, those parts were a bit vague and occasionally, they’re almost comically cliché. Where the novel shines is in how it portrays Graham, both in his relationship to the narrator and in his connection with the other time-travellers. Arthur is shell shocked, traumatised by the war and still coming to terms not only with his own sexuality but also with the fact that gay people can and frequently do come out. Graham treats him with great understanding and kindness. Margaret, on the other hand, is a ball of fun; she’s witty and delights in the possibilities that modern-day life offer her – she’s a huge cinephile and loves hot pink trousers and push-up bras – but her language is that of a seventeenth century woman, and she finds it hard to integrate.

And, of course, there is Graham’s relationship to the main character. We know they’re in love before they know it themselves, though this is a far cry from your garden variety romance novel; it’s far too layered for that. The main character herself is skilled but messy, unaccustomed to violence; she collapses when she encounters it. Graham, as someone who has seen combat, knows how she feels. He tells his own tales of the time he entered a seized slave ship, and the haunting memories it has left him with.

It’s a messy, imperfect book that could probably have done with a good editor to remove a couple of plot points, clarify a few things, kick the stupid foreshadowing to the curb and iron out the creases. It’s also a tremendously fun book, both in the light-hearted way it describes the expats’ journey into the modern world and in the more pensive approach it takes as it describes the difference between the expats learning how to ride a bike, and learning how to come to terms with everything they have missed or left behind.

I’m slightly on the fence about how I feel about using historical events and actual people for novels like this. After all, their characters are mostly conjecture. Not a lot is known about Graham Gore in particular. Bradley found whatever information she had – one image, a few descriptions from contemporaries and a few fragments of letters – and based his character on that. It’s a flattering picture of a guy who, based on what little we know of him, was affable, skilled and funny. More is known about Crozier, though we cannot be certain what happened to him ultimately; Inuit eye witness accounts have him as one of the last survivors, still trying to make his way back to civilisation. That, too, is tantalisingly used by Simmons to create an ending for the man which is almost certainly pure fiction. It is a comforting fantasy, but knowing their actual fate, you have to wonder how they would have felt about it.