On November 18, Tara Selter wakes up in Paris and goes about her day of meeting with book sellers to view and purchase rare editions for the business she runs with her husband, Thomas. She goes to sleep that night with a plan for November 19, more appointments to keep, more books to consider. When she wakes up, she slowly comes to understand that she is reliving November 18 again.

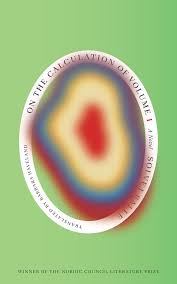

Anyone who has seen the Bill Murray classic (one of my favorite comedies, I’m not ashamed to say) will recognize the premise, but the similarities end there. In place of comedy, Danish author Solvej Balle gives us poetry.

The novel begins on Tara’s 121st November 18. Instead of a hotel in Paris, she wakes in her own home, where she listens for the sounds of Thomas waking up, getting dressed, and leaving the house. By this point, Tara has taken many approaches to understanding and attempting to rectify the time loop. When she first discovered her problem in Paris, she almost immediately called her husband to talk through it with him. “. . . it soon became plain that everything I had told him the evening before about my day was gone and that he had no recollection of his own rainy November day either. As far as he was concerned he had taken no letters or packages to the post office. He had not been down by any river, he had not gotten drenched by any shower of rain and he had no memory of our telephone conversation on the evening of the 18th.” It’s a testament to their loving marriage, which exudes from the novel’s pages, that his response to her story is cautious concern and support. They decide she should come home and sleep in their house and hope the problem rights itself. When it doesn’t, when Thomas is surprised and confused to find Tara at home when she should be in Paris, this leads to a series of many days where she convinces him over and over that she has become lost in time, only for him to forget again the next day.

This novel is fascinating in its mysterious approach to Tara’s experience. She looks for patterns but is thwarted by the seeming randomness of the rules of her new existence. Some items that she purchases (for example, some books and a coin she buys for Thomas as a gift) disappear and presumably return to their places in their respective shops, while other items remain in her possession. Food that she buys and consumes never reappears on store shelves, leading her to worry that she is slowly depleting the grocers’ supplies, as they never make it to November 19, and so are never able to restock their shelves. She starts to think of herself as a monster, consuming and taking without ever giving back. She begins living in their guest room and timing her movements with Thomas’s absences, so that she no longer has to go through the pain of telling him about her problem and seeing the confusion and desperation on his face. The more times she relives November 18, the more she feels the distance growing between them. She laments, “We could not find the mistake. We could not find the reason why time had fallen apart. There was no reason. I could not find a reason, Thomas could not find a reason. We could find patterns and we could find inconsistencies. Thomas was the pattern. I was a disturbance.”

You might well wonder how Balle keeps this story engaging for 161 pages, but she does, and the result is poetic and tragic and beautiful. This is book number one in a series of seven, and I honestly have no idea where Balle is going to take us with the next volume. I’m also slightly infuriated, because so far only the first two books have been translated into English.

This is an improbably satisfying novel. But then, as Tara observes, we should have come to expect such improbabilities: “It seems so odd to me now, how one could be so unsettled by the improbable. When we know that our entire existence is founded on freak occurrences and improbable coincidences. . . . That in this unfathomable vastness, these infinitesimal elements are still able to hold themselves together. That we manage to stay afloat. That we exist at all.”