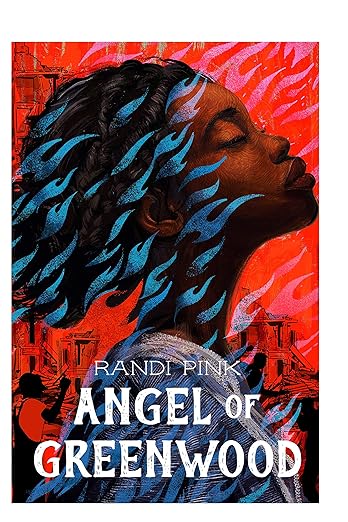

Angel of Greenwood is an outstanding YA novel about teenaged love and community set against the backdrop of the 1921 Greenwood Massacre in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Greenwood, the “Black Wall Street”, was wiped out in a vicious act of race-based terrorism with businesses looted and destroyed, houses burned to the ground and an actual bomb dropped on the community. This novel came to my attention because a local school district removed it from the 9th grade reading list, sparking protest from students, their parents and faculty. If you live in the Pittsburgh area, this story has been in the news over the past year, and recently, ContrabandCamp interviewed author Randi Pink about it.

Angel of Greenwood is an outstanding YA novel about teenaged love and community set against the backdrop of the 1921 Greenwood Massacre in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Greenwood, the “Black Wall Street”, was wiped out in a vicious act of race-based terrorism with businesses looted and destroyed, houses burned to the ground and an actual bomb dropped on the community. This novel came to my attention because a local school district removed it from the 9th grade reading list, sparking protest from students, their parents and faculty. If you live in the Pittsburgh area, this story has been in the news over the past year, and recently, ContrabandCamp interviewed author Randi Pink about it.

The novel follows a timeline starting on May 19, 1921, twelve days before the massacre. Narration moves back and forth between the main characters, teenagers Angel and Isaiah, who both live in Greenwood. Angel is a sweet girl who lives to serve. She loves books and children, but her main energies and attention are devoted to her parents. Angel’s father is unwell and growing weaker by the day. He knows he is dying and tries to prepare Angel for the inevitable. Children and older folks love Angel, but she is seen as a bit of an odd duck by her peers, and over the years she has been teased and bullied by two boys in particular: Muggy, the son of a successful Greenwood businessman, and Isaiah. Isaiah is a very smart young man who loves books and is a great devotee of WEB Du Bois. He has memorized The Souls of Black Folk and dreams of fulfilling Du Bois’ vision of Black power and equality. Isaiah’s father died in WWI, and Isaiah is angry at the way Black veterans are treated. He longs to have the courage, intelligence and vision to lead, but he also realizes that he is a coward. Muggy is a troublemaker with a reputation throughout all of Greenwood, and Isaiah lets himself get pulled into Muggy’s schemes because he fears standing up for himself.

Things begin to change for Isaiah the day he attends church services with his mother and sees Angel dance. Her beauty, grace and freedom — her lack of concern for what others might think of her — inspire him to see her in a different way. In his journal, where Isaiah secretly writes poetry, he begins writing about her. Angel, for her part, thinks little of Muggy and Isaiah. She has experienced the worst of them, and neighbors back up her negative opinion of them. When her favorite teacher Miss Ferris invites Isaiah and Angel to help her with a literacy project (bringing a library on wheels to the less affluent section of Greenwood), Angel and Isaiah gradually learn to consider each other’s opinions, see what kind of people they really are and even fall in love.

One of the sources of tension between Isaiah and Angel has to do with the historical debate between Booker T Washington and WEB Du Bois regarding how Blacks should deal with whites. Angel and Isaiah attend Booker T Washington High in Greenwood, and Angel is a fan of Washington’s Up From Slavery. Isaiah is disdainful of Washington’s tolerance of discrimination and segregation. Angel sees Du Bois as a hothead whose anger will only lead to violence; patience and a focus on what you can do for your own community is the better path. There is a passage in the novel where Angel and Isaiah engage in a very heated debate about this in front of Miss Ferris, who provides a level-headed assessment of the two sides and an explanation of the guilt many Blacks feel, particularly in Greenwood. This passage is very well written and I found it enlightening.

Of course, as the days pass, the reader knows that we are getting closer to the horrible hateful Greenwood massacre. Randi Pink’s writing here had me on the edge of my seat and in tears. Our main characters, awake late into the night, see the city burning from a distance and have to act to try to save as many people as they can. The sense of terror and of loss comes through on every page. This tragedy of US history has only recently been added to textbooks, and if the current administration has its way, it’ll probably be censored out again. It infuriates me that school districts, led by fearful white parents, intervene to prevent teachers from using novels like this in class — novels that are well written, focus on teens, provide necessary historical context and provoke meaningful reflection and conversation in a way the A Tale of Two Cities just does not (that’s the book that the school board wanted added back into the curriculum instead of Angel of Greenwood). I highly recommend Angel of Greenwood if you are interested in US history, banned books, and teen lit.