While never a huge David Sedaris fan, I started to appreciate his approach to writing when I read the excerpts from his personal diaries during the pandemic. Sedaris focuses on the little, absurd things in life and weaves an essay around them. His off-the-wall, probing questions might seem unsettling to some, but I suspect he’d make a fantastic dining companion and a hoot to have at parties. For example, in an essay titled “Six to Eight Black Men,” he talks about how he makes a point of asking taxi drivers in other countries things like “When do you open your Christmas present?” How I wish I had the courage and creativity to ask strangers such questions, rather than the conversational softball, “Are you just starting your shift?” The title of the essay comes from the intel he received from several Dutch people that Saint Nicholas isn’t aided by elves (which are apparently considered silly), but by six to eight black men (originally these helpers were slaves, but nowadays Dutch people know that they are just Santa’s good friends).

While never a huge David Sedaris fan, I started to appreciate his approach to writing when I read the excerpts from his personal diaries during the pandemic. Sedaris focuses on the little, absurd things in life and weaves an essay around them. His off-the-wall, probing questions might seem unsettling to some, but I suspect he’d make a fantastic dining companion and a hoot to have at parties. For example, in an essay titled “Six to Eight Black Men,” he talks about how he makes a point of asking taxi drivers in other countries things like “When do you open your Christmas present?” How I wish I had the courage and creativity to ask strangers such questions, rather than the conversational softball, “Are you just starting your shift?” The title of the essay comes from the intel he received from several Dutch people that Saint Nicholas isn’t aided by elves (which are apparently considered silly), but by six to eight black men (originally these helpers were slaves, but nowadays Dutch people know that they are just Santa’s good friends).

The point is, Sedaris has a gift for finding and noting the unexpected while sifting through the ordinary. I love this approach to writing. Sometimes I love the results; sometimes I just feel discomfited.

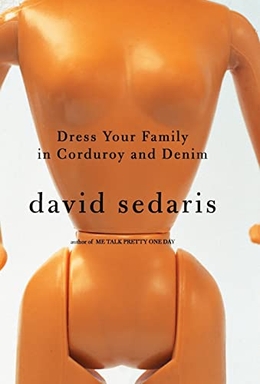

There’s a fair bit of heartbreak in Dress Your Family in Corduroy and Denim that touch on Sedaris’s family and his formative years. In the first essay, “Us and Them,” he talks about how his family moved a lot when he was a kid, and he picked up his mother’s habit of not getting too close with any of the neighbors. He reminisces that “it allowed me to pretend that not making friends was a conscious choice.” He undercuts that sadness by recounting how one family that he really liked lost his favor by daring to go trick-or-treating the day after Halloween. “Asking for candy on Halloween was called trick-or-treating, but asking for candy on November first was called begging, and it made people uncomfortable.”

Much of Sedaris’s writing focuses on his struggles to make friends, his struggles to come to terms with his sexuality, his struggles with his family. Sometimes it hurts to read the jokes and feel the pain that’s happening underneath them. When he recounts the story of his father kicking him out of the house, his father just says, “I think we both know why I’m doing this.” Young David assumes it’s because he’s a bum, or a drug addict, or a sponge. He doesn’t find out until months later that his dad kicked him out for being gay. Of course, as readers, we can never really know where the real David ends and David the character begins, so perhaps feeling pity is out of line. I’m never really sure when I’m supposed to be laughing, though, and I have to admit that makes uncomfortable.

For having such obvious talent, Sedaris makes me weary anytime I delve into a collection of his work. I start off admiring, but by the time I get to the end, I feel like I’ve been eating the same meal for a month straight and just want a change. I’ve come to the conclusion that I need to treat these essays like small bites–perhaps reading his essays as one-offs in the New Yorker or listening to them on NPR are better ways to enjoy them.