The numbers of AIDS cases measured the shame of the nation….The United States, the one nation with the knowledge, the resources, and the institutions to respond to the epidemic, had failed. And it had failed because of ignorance and fear, prejudice and rejection. The story of the AIDS epidemic was that simple….it was a story of bigotry and what it could do to a nation.

I moved from New York to San Francisco in 1990, when I was 21 years old. I vividly remember sitting at an open air cafe in the Castro with one of my good friends, who was gay. He was skimming the Bay Area Reporter newspaper’s obituary page. Obituary followed obituary in long columns, with black and white pictures of the dead, who had died of AIDS. My friend pointed out all the men he knew. He had experienced this ritual many times.

I moved from New York to San Francisco in 1990, when I was 21 years old. I vividly remember sitting at an open air cafe in the Castro with one of my good friends, who was gay. He was skimming the Bay Area Reporter newspaper’s obituary page. Obituary followed obituary in long columns, with black and white pictures of the dead, who had died of AIDS. My friend pointed out all the men he knew. He had experienced this ritual many times.

Randy Shilts’s And the Band Played On: Politics, People, and the AIDS Epidemic, is a detailed account of the rise of the AIDS epidemic from 1980 to 1988, from the end of the carefree, joyous gay liberation days to the spread of AIDS across the world. The book focuses on the infuriatingly slow response of the federal and local governments to address the epidemic, the effect of homophobia on this slow response (and in many cases non-response) to the devastating disease, and the ways in which the gay community itself was slow to face the fire that was sweeping through their community.

The failed response to the epidemic over the course of almost a decade was influenced by many things, particularly understandable fears among the gay community that they would be further ostracized by the disease that was killing them if too much attention was paid to their circumstances. There were protests about closing the bathhouses where many gay men had sex with multiple partners. Men were angry that their sexuality was being pathologized, after long and ongoing efforts to gain equal rights. The excuse of the health crisis gave homophobic conservatives yet another reason to virulently hate and oppress gays. As Shilts writes, this tension between not pathologizing gay men for their sexual practices and riling up prejudice in bigots had ruinous effects:

Don’t offend the gays and don’t inflame the homophobes. These were the twin horns on which the handling of this epidemic would be torn from the first day of the epidemic. Inspired by the best intentions, such arguments paved the road toward the destination good intentions inevitably lead.

However, there were many heroes who discovered the early-named “gay cancer” was in fact to be the scourge of our times. Some were medical professionals, some were gay activists, some were political figures. It was often like trying to get someone’s attention in a howling storm. People turned deaf ears, dismissed the “hysterics,” turned away from something that they thought didn’t and wouldn’t affect them. The illness that caused people to die in horrific ways received little attention in publications until heterosexuals were struck with the disease.

And the Band Played On is over 600 pages, but it is written so well, with such a good balance between individual men’s stories and the bureaucracy that caused more deaths due to its deliberately slow response, that I found it thoroughly absorbing. It reminded me of the stories of those I have known who were lost to AIDS: a close friend in high school, my first boyfriend, a family friend, and others. It reminded me of sitting in that San Francisco cafe with my friend on that beautiful sunny day, reading over those who had died.

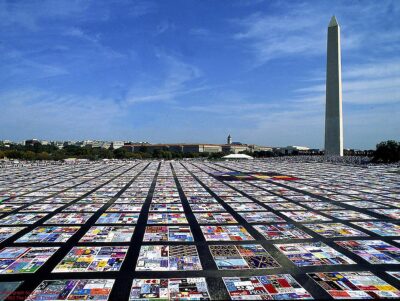

Shilts includes scenes of some triumph among the continuing hardships. There is the creation of the AIDS quilt and gay mens’ formation of groups to educate and take care of the afflicted. And there is this scene from San Francisco’s Gay Pride parade in 1985:

The outward push for power continued, but it was largely eclipsed by the inward struggle for grit in the face of some of the cruelest blows that fate had meted out to any American community. As gay people had helped each other find this strength, they had forged a gay community that was truly a community, not just a neighborhood. And by now, there was also a shared sense that they wanted the dream to survive. It had been a painful and difficult five years to reach this point, but it had come this day.