I really enjoyed A Complete Unknown, the Bob Dylan biopic starring Timothee Chalamet. I had a huge Bob Dylan phase as a young man and still listen to him frequently, but I wouldn’t call myself a true Dylanologist. Still, the made me intrigued about the infamous performance at the Newport Folk Festival where Dylan went electric.

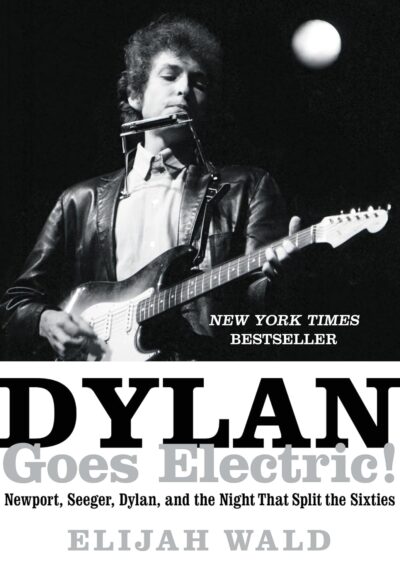

The movie is an adaptation of Elijah Wald’s Dylan Goes Electric!: Newport, Seeger, Dylan, and the Night That Split the Sixties. Wald covers the event itself in great detail, of course, but more importantly, he lays the groundwork leading up to it. Wald breaks down the major personalities that clashed, the traditions they represented, and the differences of opinion that broke them apart.

Wald goes through Dylan’s arrival in New York, his ingratiating himself with both Seeger and his idol Woody Guthrie, his first forays into performing at the Greenwich Village folk clubs, and his meteoric rise to prominence as a songwriter and reluctant voice of a generation. Wald does an excellent job establishing the parameters of the folk scene as a whole, from the commercial acts that took off despite being looked down upon by purists (like The Kingston Trio and Peter, Paul, and Mary) to the “real-deal” folkies like Seeger, Joan Baez, and 1,000 other acts you may not have heard of if you aren’t an obsessive or a connoisseur.

Wald also lays out the history of the Newport Folk Festival, its creation, its vision, and its rise to prominence in advance of Dylan’s historic performance. Pete Seeger was the visionary behind the original concept of the festival, and his imprint is best seen in the varied acts that filled the festival bill. Seeger was truly committed to authentic American art forms, like old-time blues singers from the Deep South, bluegrass bands, jug bands, and on and on. Some of these bands bewildered and annoyed the young crowd who showed up mostly for Dylan and Joan Baez, while those young people in turn annoyed and bewildered the traditionalists.

As to the night in question, Wald is better at explaining what Dylan’s performance meant as opposed to what actually happened. What happened will always remain in contention, as no two people had the same experience of the event. Did the crowd boo Dylan off the stage, or was there a mix of boos and cheers? Were the boos because Dylan was playing electric, or was it because the sound was too loud and people couldn’t hear him singing? Did Pete Seeger really have an axe, or did he just wish that he had one? Either way, the impact was undeniable. The folk revival never recovered, Dylan became a superstar and an indelible symbol of the sixties even as his motorcycle accident took him out of the public eye for years, and the Newport Folk Festival hung on for a few more years before shutting down (it has since been revived, more or less successfully.)

Wald is also excellent at delineating the central irony of the Dylan-Seeger dichotomy: that the idealistic youth chose the side of the man who refused to become a part of the movement, and rejected the committed leftist, pacifist, and believer in equality.

Dylan Goes Electric is sometimes clogged up with names and facts, but for anyone with a real interest in the story, this is the closest thing to a definitive account you’re likely to find.