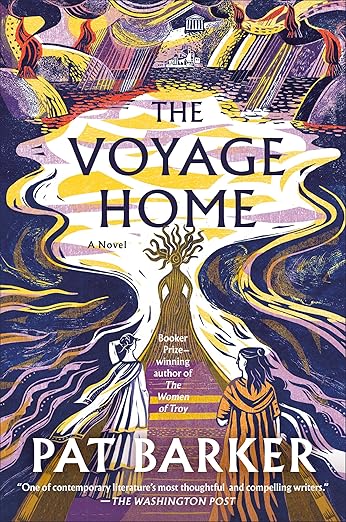

The Voyage Home is Pat Barker’s final installment in her Women of Troy trilogy. The first two novels, The Silence of the Girls and The Women of Troy, take on the events of The Iliad and imagine them from the point of view of the vanquished, in particular from the point of view of the Trojan women who became enslaved to the victorious Greek armies. The princess Briseis, who became Achilles’ concubine/slave, was the primary focus of those novels, which were brutally realistic in their portrayal of war and its abuses, especially the sexual abuse of women. Barker’s women are pragmatists and realists who don’t have much time for the gods. They understand that what happens to them is not because of some divine design but solely due to the arrogance and aggression of men grasping for power and acclaim. I highly recommend both of those novels. In book three, Barker’s attention turns to Cassandra, Agamemnon, and Clytemnestra, with much of the story imagined through the eyes of the enslaved Trojan woman Ritsa. Cassandra, of course, is the priestess whose curse is that she can prophesy the future but no one believes her prophecies. Ritsa’s master Machaon, who is a Greek healer attached to the armies, has lent Ritsa to Agamemnon to attend to his war prize Cassandra. This novel is the imaginative story of Cassandra and Agamemnon’s return to Mycenae and the violent events that ensue. While gods and goddesses are absent from the story (as was the case in the previous two novels), there is a surprising supernatural element to this novel — children’s ghosts. It seemed a little odd at first, but this is a novel about child abuse and trauma and about the guilt and anger of adults who witnessed it.

The Voyage Home is Pat Barker’s final installment in her Women of Troy trilogy. The first two novels, The Silence of the Girls and The Women of Troy, take on the events of The Iliad and imagine them from the point of view of the vanquished, in particular from the point of view of the Trojan women who became enslaved to the victorious Greek armies. The princess Briseis, who became Achilles’ concubine/slave, was the primary focus of those novels, which were brutally realistic in their portrayal of war and its abuses, especially the sexual abuse of women. Barker’s women are pragmatists and realists who don’t have much time for the gods. They understand that what happens to them is not because of some divine design but solely due to the arrogance and aggression of men grasping for power and acclaim. I highly recommend both of those novels. In book three, Barker’s attention turns to Cassandra, Agamemnon, and Clytemnestra, with much of the story imagined through the eyes of the enslaved Trojan woman Ritsa. Cassandra, of course, is the priestess whose curse is that she can prophesy the future but no one believes her prophecies. Ritsa’s master Machaon, who is a Greek healer attached to the armies, has lent Ritsa to Agamemnon to attend to his war prize Cassandra. This novel is the imaginative story of Cassandra and Agamemnon’s return to Mycenae and the violent events that ensue. While gods and goddesses are absent from the story (as was the case in the previous two novels), there is a surprising supernatural element to this novel — children’s ghosts. It seemed a little odd at first, but this is a novel about child abuse and trauma and about the guilt and anger of adults who witnessed it.

If you are unfamiliar with the story of Cassandra and Agamemnon, of Clytemnestra, and of Electra and Orestes, this might be a bit spoilery. I feel like those stories are pretty well known though so I have no qualms about being specific about what happens. When The Voyage Home opens, the Greek ships are finally leaving Troy. It has been 10 years and they have vanquished the Trojans, killing all the men and boys, enslaving the women and girls. Agamemnon, known for his insecurity, arrogance and violent temper, has taken Cassandra, daughter of Troy’s King Priam, as his concubine. Cassandra is 25 and has striking looks but also has a reputation for being crazy. She rants about the future but no one takes her seriously. Ritsa, the enslaved woman tasked with attending to her, finds Cassandra tiresome and occasionally challenges her about her prophecy regarding Agamemnon, i.e, that Cassandra and Agamemnon will die shortly after reaching his palace at Mycenae. Ritsa thinks this is daft and that Cassandra, pregnant with Agamemnon’s child, is in an advantageous position. Cassandra hates Agamemnon (as all the enslaved women do) because she saw the murder of Trojan children and men firsthand. She believes that for the prophecy of Agamemnon’s death to come true, it is essential that she die also. Revenge/vengeance is a theme that runs throughout this story (as it does through a lot of classical literature). Cassandra longs for this justice to finally be realized.

Cassandra and the Trojan women are not the only ones who want to exact revenge on Agamemnon. Back in Mycenae, Queen Clytemnestra has been planning to murder her husband for 10 years. When the war started, the Greek armies were stuck at Aulis due to unfavorable winds. A priest told Agamemnon that he must make a significant sacrifice to appease the gods, and given the importance of the war and his desire for glory, Agamemnon sacrificed his 15-year-old daughter Iphigenia. Clytemnestra was unaware of this arrangement until she saw her daughter sacrificed, and her grief has been all consuming. Clytemnestra nonetheless has been a very capable ruler for her country despite patriarchal prejudices against her. Her goal is to kill Agamemnon and secure the throne for her son Orestes, who is abroad. Clytemnestra does not account for the feelings that her son and other daughter Electra might have about their father.

In addition to the suffering and death of Iphigenia and the Trojan children at the hands of Agamemnon, there is also Agamemnon’s father’s horrific crime screaming out for vengeance. A generation ago, Atreus murdered his nephews and fed them to his brother as revenge for committing adultery with Atreus’ wife. In the palace at Mycenae, many people can hear strange voices, children’s voices, singing menacing songs, and some even see their ghosts. Strange handprints and footprints can be found around the palace grounds (Atreus saved his nephews’ hands and feet to taunt his brother after their gruesome dinner). Ritsa and Cassandra hear the voices constantly and Ritsa has a terrifying encounter with the ghosts herself.

The combination of trauma and a desire for revenge lead to never-ending misery. This is true in Greek myths and throughout history. Barker’s descriptions of women’s trauma at seeing children suffer and die are haunting; these women feel anger at the murderers and guilt at their inability to stop them. So much senseless death can drive a person mad and make them desperate, as is evident in the extreme actions taken by both Clytemnestra and Cassandra. I couldn’t help but think of the suffering of children in war zones today and the impact it will have on adults impotent to stop it.

The Voyage Home is not just the retelling of Cassandra and Clytemnestra’s stories. It is also the story of Ritsa, the middle class Trojan woman who lost her spouse and child, then became enslaved and a healer. In some ways she is no different from Cassandra and Clytemnestra. Ritsa has suffered; not only has she seen the deaths of people she loved, but she has also been raped and ministered to other rape victims. Yet Clytemnestra and Cassandra, having come from power and privilege, felt a burning need for revenge in a way that Ritsa never did. Despite her enslaved status, Ritsa finds herself with choices — about whether to take revenge when given the chance, about which direction she wants her life to take. We know what happens to Clytemnestra and Cassandra, but through Ritsa we see a different response to the upheaval, violence and trauma, one that breaks away from the cycle of revenge and seeks out healing. It is not easy.

Overall, I would say this is a strong finish to the trilogy but all three books deal with triggering issues so beware.