To be fair, only half of this is Catholic trauma porn. One may wonder why Ireland, of all places, has spawned such a fabled literary heritage. Personally I think it’s their sly sense of humour, finely tuned after years of British occupation. Perhaps it’s the potatoes. Both of these books abundantly feature potatoes.

To be fair, only half of this is Catholic trauma porn. One may wonder why Ireland, of all places, has spawned such a fabled literary heritage. Personally I think it’s their sly sense of humour, finely tuned after years of British occupation. Perhaps it’s the potatoes. Both of these books abundantly feature potatoes.

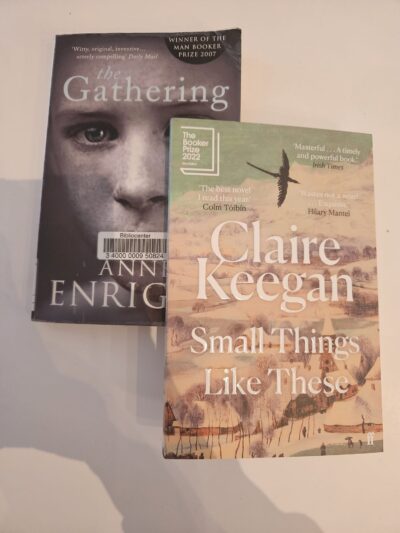

Small Things Like These (Claire Keegan) ***

Bill Furlong is a coal merchant in a small town in Ireland in 1986. It’s nearly Christmas; the busiest time of the year for him. Bill had a rough upbringing, though, as he soon discovers, not nearly as rough as it might have been: his mother was unmarried, his father unknown. Her employer, a wealthy protestant woman, took them in and made sure Bill did well in life. Bill had stability and people who loved him, but still the gap of not knowing his father aches. Decades later, he has his own family: his wife, dutiful in that no-nonsense way, and five daughters who sing in the church choir and do well at school. He’s the epitome of Catholic respectability. So when he makes a delivery of coal to a Catholic convent in the town, he is shocked to discover what is behind the gates.

There is a strange, timeless feel about this short novel. The Ireland that Furlong inhabits is caught in that particular fugue state between old and new: life is changing rapidly, yet not at all. Scenes Furlong describes, of hungry children drinking the milk left out in a saucer for the cat, could have come straight out of the 19th century. His home life, too, is sedate and static, dominated by habits that have been left unchanged for decades, if not longer. Bill occasionally longs to break the silence, and the habits. It’s telling, in more than one way, that the people around him tell him not to stir the hornet’s nest. We know what will happen if he does it. Bill does, too. The fact that this doesn’t stop him speaks for his character and, I suppose, for the changes sweeping though society, though the last Magdalen laundry didn’t close until 1996, a full decade later.

The novel is short; it’s barely a novella, at a good 100 pages. The writing is effective and mirrors Furlong’s personality, his habits of keeping things to himself and getting on with it. No malingering, not a word wasted. It’s good writing, but I occasionally missed a spark in the novel. I’m also not sure I enjoyed the point where the story ended: I understand Keegan’s choice to pause the story where she did, both because it’s a hopeful coda and because I think we can all predict how the story will play out. But it’s undoubtedly a well-written treat of a novel. I’m just not entirely sure it was for me.

The Gathering (Anne Enright) ****

In early 1990s Dublin, the Hegarty of eleven gather at the wake of their brother Liam, who has walked into the sea with no socks, no shoes and his pockets full of rocks. Narrator is Veronica, one of the middle children. Veronica’s mother forgets her name. Her husband might hate her, she suspects, and she finds that she doesn’t care. She struggles to come to terms with her brother’s death while dealing with her siblings. The dynamics of a family of twelve are, as one might suspect, complex, and Veronica’s bond with Liam wasn’t always good, but she did love him, and she misses him. Part of her has always suspected Liam would end up like this, because of what happened to Liam in his grandmother’s house, in 1968.

In terms of literary merits, it’d be hard to match this book. It’s fiendishly clever and, despite the raw current of grief and despair, very, very witty; aware of its own heritage – “There is always a drunk”, Veronica informs us, “and always someone who was interfered with as a child”. Veronica is very self-aware and a keen observer, though the novel mostly takes place in her own head as the narrative leaps back and forth between the life of Ada, Veronica’s grandmother, as she imagines it, and Veronica’s own life, her childhood, the present day. I’m not a huge fan of stream of consciousness-writing – too muddled, too convoluted, and it requires too much of my attention in a time period when I barely have the brainpower to function. Nevertheless, I quite enjoyed reading this book.

The impressive thing is how it manages to tick every box on the list of the Clichés in Irish Fiction, but it is self aware enough to avoid this potential pitfall. Veronica’s mother, for example, is a perpetually befuddled woman for whom Veronica has little patience; a woman whose entire identity seems to revolve around her ability to birth others (twelve children, seven miscarriages; an impressive tally, even by Irish Catholic standards). The way Veronica speaks about her, and her father too, suggests she was happy to escape their daily presence, and she is all too aware that it is duty that drags her back in, at the detriment to herself.

The house that the Hegarty clan grew up in started out small, but annexes, rooms, hallways and extensions were added as their brood grew until the house was a jumbled mess of lean-tos and chambers full of memories and echos. This, more or less, is what the novel is like as well: unstructured, wild, full of heartbreak and fun and pain and humour. It’s a tour de force of writing.