Two relatively short, easy reads this week, neither of them terribly cheerful!

Two relatively short, easy reads this week, neither of them terribly cheerful!

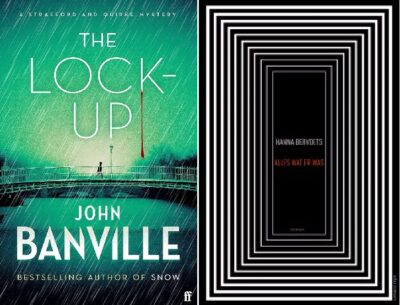

The Lock-Up (John Banville) ***

1950s Dublin. A young woman is discovered in a rented garage, sitting in her car with the windows closed and a hose connecting the exhaust to the interior. The police are quick to call it suicide, though no note is found. But pathologist Quirke, still in mourning over the loss of his beloved wife, soon discovers that the young woman was probably sedated before being placed inside the car – meaning it is a murder, not a suicide.

This is the third instalment of Banville’s Quirke and Strafford novels. I like that Banville – an artsy-fartsy Booker laureate – has branched out into a different genre. Do not go into this series looking for complex murder mysteries with a satisfying, clean end; they rarely arrive. Instead, Banville focuses on the characters, their dynamics and their feelings. He’s the sort of author who, by his own admission, can agonise over a single sentence for hours, and it shows in the sense that the prose perfectly reflects the characters’ troubled state of mind, both for the grieving Quirke and for the buttoned-up Strafford, whose wife has left him (he is unsure of how permanent the arrangement is).

There were things I didn’t like about this novel. While the women are far from clichés, they rarely stray outside the middle-aged equivalent of the manic pixie dream girl: beautiful, ethereal and super duper into sex with the main characters. Quirke’s antagonistic response to Strafford, whom he partially blames for the death of his wife, is a little melodramatic compared to the rest of the novel.

Other things, though, are rather well-done. Ireland of the 1950s was a place where many things went unspoken and where the Catholic church had a heavy say in everything, from politics and policing to education and health care. Banville skillfully manages to highlight this without losing subtlety. Where he does go off the rails a bit is in the last chapter; the whodunnit is a bit unsubtle, though i did like the frustrating nature of it. Banville’s novels rarely have a clear resolution and this one is no exception. That, and his wonderfully evocative prose and attention to detail, makes his books worth reading.

Alles Wat er Was (All that there was) (Hanna Bervoets)

A group of eight people are at a school, on Sunday. They are making a documentary about a child prodigy. Just as they’re filming filler material, a loud bang is heard. Sirens go off. The radio tells them to close the curtains and blinds, tape off all vents, and stay inside. Then, communication is cut off. People who venture outside disappear into a thick, grey fog and are never heard from again. The survivors stay behind, wondering what to do as they try to combat boredom and struggle to subsist on increasingly meagre food rations.

This is a bleak novel. I’d never heard of it before, but I’d read the author before and the plot seemed interesting, so I gave it a go. I guess apocalyptic novels are never particularly cheerful and this is no exception. The mundane bickering seems realistic enough, as is the fact that everyone almost immediately takes up a particular role in the group, something the main character Merel, quietly observes.

Things escalate after an incident that injures the child, and Merel finds empty pill bottles that once contained antipsychotic drugs. People accuse each other of all sorts of things; people leave and are never heard from again. As the novel progresses, Merel becomes more and more unhinged and the novel becomes less linear.

It’s not a bad book, per sé, but it is a frustrating one and it reminded me of why i dislike dystopian and apocalyptic novels. Bervoets gives her main characters just enough to be interesting; it’s their dynamics that matter, and as one might expect of a small, isolated group facing a lot of pressure, things become increasingly unhinged.

This was a fairly quick read for me and it was interesting enough, but ultimately I don’t think this book is for me.