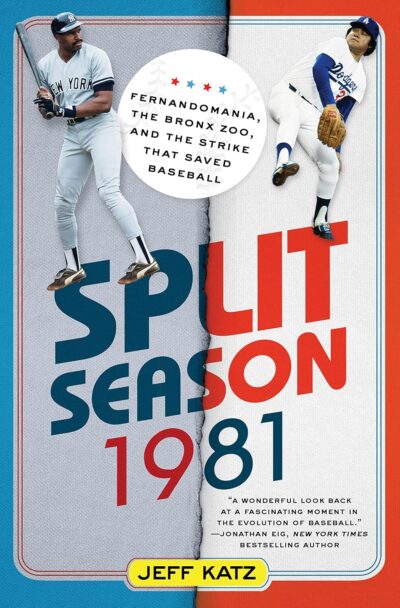

As you may have heard, the Dodgers and Yankees recently met in the World Series, with the Dodgers ultimately prevailing. If you watched the games, you probably also heard that it was the first matchup between those two teams in the Fall Classic since 1981, when, coincidentally, the Dodgers also came out on top. Finally, you also likely heard about the recent passing of Fernando Valenzuela, who was the biggest star in baseball in 1981, winning both the Rookie of the Year and Cy Young Awards, a feat which had never before been accomplished.

This confluence of events inspired me to finally pick up Jeff Katz’s Split Season 1981. I have been meaning to read it for a long while, because the 1981 season has always intrigued me. That’s because it is a totally unique season in baseball history. The players went on strike in the middle of the season and almost two months worth of games were lost. That alone would make the season of interest to any fan of baseball history, but on top of that is the truly bizarre decision that the owners and commissioner’s office made upon the players’ return. The decided that the season would be split into two halves. The teams that had been in first place when play was stopped by the strike were thus automatically granted playoff berths. All the teams essentially got a do-over for the second-half of the season, with only their record in that half counting toward their playoff hunt.

Every time I’d heard about that decision, I never heard the reasoning behind it. It’s always seemed absurd to me, and indeed the results were absurd. The teams that had already secured playoff berths had no real incentive to play hard in the second half, so most did not. The Cincinnati Reds had the best record in baseball for the whole season, but because they finished second in each half, they didn’t make the playoffs at all. Getting the answer to why that seemed acceptable to everyone involved is basically the whole reason I bought this book.

Of course, to get there I had to get through the first half of the season and the strike itself. The on-field discussion was dominated by Fernandomania. After throwing a shutout in a surprise start on Opening Day, Valenzuela continued dominating for months, becoming a national star at 20 years old. Len Barker of the Cleveland Indians threw a perfect game. Pete Rose was chasing down Stan Musial’s National League hit record of 3,630. Dave Winfield, fresh off signing the largest free-agent contract in the history of professional sports, was struggling in the Bronx, while his teammate Reggie Jackson was worrying about what Winfield’s contract meant for his own upcoming free agency.

The strike loomed over the season from the start, after a one-year reprieve during the 1980 season. At issue was the owners trying to limit the impact of free-agency, which had sent salaries for star players soaring. Even though baseball was becoming more popular and more lucrative, the owners were crying poverty, which also refusing to let the players’ union inspect their books. They wanted to punish teams for signing free agents in order to disincentive the practice, which the union obviously opposed.

This part of the book really drags on, partly because the negotiations themselves dragged on due to owners’ intransigence, partly because labor disputes in general are not particularly interesting. Katz is clearly on the side of the players union, but that seems fair from a historical perspective. Eventually, the union won because of their impressive unity, while the owners devolved into factions based on their financial incentives. The twenty-six rich men who owned MLB teams were not used to working together as a team, and it showed.

Eventually, the strike was settled largely because the owners’ strike insurance money was about to run out. They got some of what they wanted, but not much, and the union’s strength was well-noted. The owners got to decide how to handle resuming the season, and it was them who came up with the split season concept. The reason? Attendance. The owners were concerned that the strike would turn fans off from the national pastime, and thought that instantly putting every team back into the pennant chase would help matters. It didn’t really work, and as a bonus it made a mockery of the playoffs, with Kansas City making it despite a record well under .500.

Katz somewhat oddly races through the 1981 playoffs, dispatching with whole series in a couple of paragraphs after spending multiple chapters on the labor negotiations. There were some memorable moments that October, including Montreal’s first ever postseason appearance, and the return of A’s manager Billy Martin to New York for a series against the Yankees he had managed a few years before.

If the end of the book and the end of the season were slightly disappointing, there are still some fascinating character studies on hand. Reggie Jackson is a fascinating guy, full of contrasts. Marvin Miller, the head of the players union, comes off as principled and insightful. Commissioner Bowie Kuhn looks like a fool poorly suited for his job. George Steinbrenner was at the height of his antics in 1981, temperamental and intractable.

Split Season 1981 takes an in-depth look at one of the strangest years in baseball history, and if it doesn’t necessarily capture the game at it’s best it’s still an informative, fun read.