These three books sum up the span of photojournalism pretty well, both in time and stylistically. I am not so much an art photography person, nor someone who likes books of just photographs without captions, even if I am a big fan of the photographer. For me, the captions offer the context that make the image more meaningful to me.

These three books sum up the span of photojournalism pretty well, both in time and stylistically. I am not so much an art photography person, nor someone who likes books of just photographs without captions, even if I am a big fan of the photographer. For me, the captions offer the context that make the image more meaningful to me.

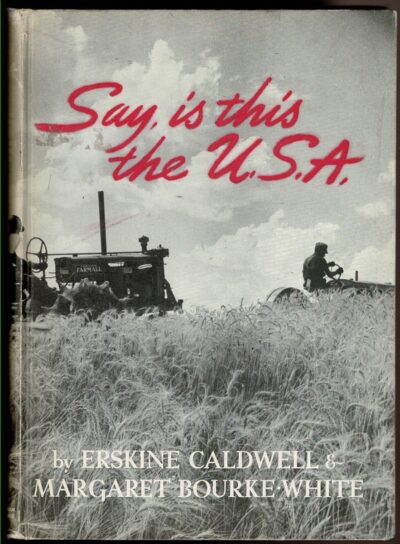

Say, is this the U.S.A. is a collaborative tour through the USA in 1941, with Margaret Bourke-White providing some great photographs and Erskine Caldwell writing the narrative of their trip. 1941 provided a good year for this book, as whether or not the US will enter WWII is very much up in the air, and the country is just coming out of the Great Depression. It’s always interesting to see through the myth that everyone was on board with entering the war. We hear a range of opinions here, including one memorable one that we’ll have to keep making money supplying the war so Germany and England need to keep fighting for another two years. This book also shows how the past really is another country. There’s one horrifying scene in Kansas where a young Black teenager is forced off a train because he has no ticket, even though they’re fifteen miles from the nearest station and it’s below freezing and snowing. The casual way in which the train conductor refuses to take anyone else’s money on the teen’s behalf and shoves him out the door into the snow, potentially to his death, while saying “He’s a n—-r, ain’t he?” drives home the pervasive and appalling racism that is present in so much of our history. Here, this is told as a throwaway story, and the book continues on with no other commentary. I’m glad I picked this up but I don’t think it’s a keeper for me because it is less of a photojournalism book (more of a travel narrative) and I’m trying to keep my collection narrow.

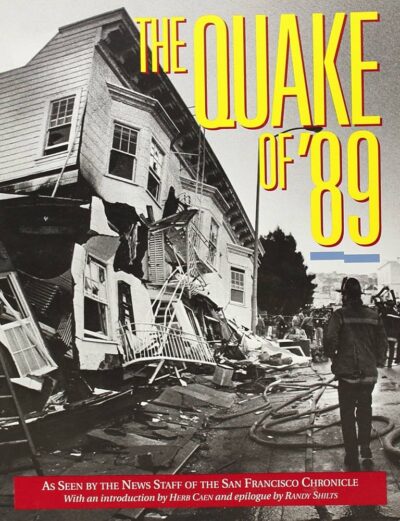

The Quake of ’89, on the other hand, is a keeper for me. It’s less artistically done and it doesn’t have famous names attached to it, but I think it captures something only newspaper photojournalism can — very precise moments in time, the average person’s point of view, the raw stuff of life. The book is divided into themed sections, such as “Horror,” “Anguish,” and “Hope,” and each section has photos and brief blurbs to go with them. There are some very strong photos in here, especially one from Liz Hafalia of a woman waiting to hear about her husband’s condition after her sister has died on the Bay Bridge. Hafalia captures such genuine emotion in her photo and in such a striking way that it was the main photo of the book for me. I knew the basic facts of this earthquake but it was good to learn more of the individual stories. I also hadn’t thought as much about the issue of homelessness afterwards and the question of where people can go after their apartment building needs to be knocked down (chalk that naivete up to my earthquake-less life on the East Coast). This also had me thinking about what we lose in terms of knowing local stories with the loss of newspapers and long-term photographic staff members.

The Quake of ’89, on the other hand, is a keeper for me. It’s less artistically done and it doesn’t have famous names attached to it, but I think it captures something only newspaper photojournalism can — very precise moments in time, the average person’s point of view, the raw stuff of life. The book is divided into themed sections, such as “Horror,” “Anguish,” and “Hope,” and each section has photos and brief blurbs to go with them. There are some very strong photos in here, especially one from Liz Hafalia of a woman waiting to hear about her husband’s condition after her sister has died on the Bay Bridge. Hafalia captures such genuine emotion in her photo and in such a striking way that it was the main photo of the book for me. I knew the basic facts of this earthquake but it was good to learn more of the individual stories. I also hadn’t thought as much about the issue of homelessness afterwards and the question of where people can go after their apartment building needs to be knocked down (chalk that naivete up to my earthquake-less life on the East Coast). This also had me thinking about what we lose in terms of knowing local stories with the loss of newspapers and long-term photographic staff members.

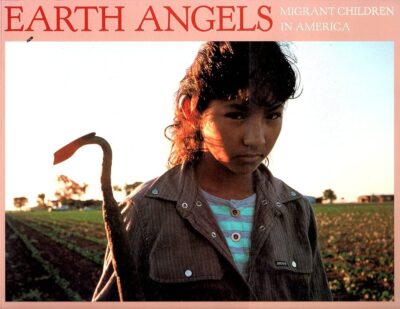

Earth Angels falls into the more consciousness raising/social issue category, like Donna Ferrato’s Living With The Enemy, one of my all time favorite books. Here, Buirski focuses on the lives of migrant children and the impact that working on farms has on them. One shocking fact I learned was that the average life expectancy in the US (in 1994, when this book was published) is 73, but for farm workers it is 49. Continuous exposure to pesticides seemed like a big contributor to this from the information provided. The photos are very good and convey a lot about the grinding poverty and inhumane living conditions provided to these families by the farm owners. The book also highlights the positive side of the close bonds of family and the happiness that is shared among the family unit. I’m glad I picked this up and will add it to my collection.

Earth Angels falls into the more consciousness raising/social issue category, like Donna Ferrato’s Living With The Enemy, one of my all time favorite books. Here, Buirski focuses on the lives of migrant children and the impact that working on farms has on them. One shocking fact I learned was that the average life expectancy in the US (in 1994, when this book was published) is 73, but for farm workers it is 49. Continuous exposure to pesticides seemed like a big contributor to this from the information provided. The photos are very good and convey a lot about the grinding poverty and inhumane living conditions provided to these families by the farm owners. The book also highlights the positive side of the close bonds of family and the happiness that is shared among the family unit. I’m glad I picked this up and will add it to my collection.