CBR16 BINGO: Golden, because the novella Eve in Hollywood takes place during the Golden Age of Hollywood

CBR16 BINGO: Golden, because the novella Eve in Hollywood takes place during the Golden Age of Hollywood

BINGO: Part 1, Part 2, Dreams, Golden, Scandal

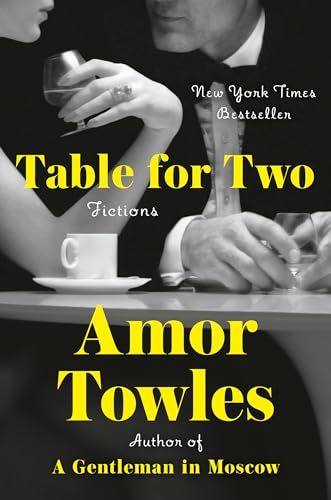

I was so taken with A Gentleman in Moscow that the gathering up and devouring of more of Amor Towles’s works became inevitable. While not quite reaching the same level of charm as the aforementioned tale of a Russian aristocrat, Table for Two is a solid collection of short narratives that mingle humor, tragedy, and resilience.

Table for Two feels like two books; it’s divided into five short stories that take place partially or completely in New York, and one novella, Eve in Hollywood, that takes place in Los Angeles. Some common themes run through the book, but Eve in Hollywood could have been a stand-alone novella.

The short stories

Although the short stories mainly take place in New York in the early days of the 21st century (that’s post 2000, and I can’t even believe I just typed that), “The Line” begins in Russia in the “the last days of the last Tsar.” Irina and Pushkin are Russian peasants who move to Moscow at Irina’s insistence. When kind-hearted Pushkin proves inept at holding down a city job, he becomes the house husband, which mainly consists of standing in long lines for bread and milk and tea. His affability soon turns the lines of dour citizens into a community. “It didn’t take long for the citizens of Moscow to realize that if you had no choice but to stand in line, then Pushkin was the man to stand next to. Graced with a gentle disposition, he was never boorish or condescending, neither full of opinions nor full of himself.” One day, Pushkin offers to hold a place in line for a neighbor who needs to get to the pharmacy before it closes, something that, were anyone else to suggest it, would start a riot. (Communist food lines enforce a strict “No savies” policy). His line-saving and people-pleasing skills eventually lead him to the line for the Agency of Expatriate Affairs, where Russians who wish to get a Visa to leave the country must wait. He’s just doing it for another friend, but . . . you can see where this might lead. Of all the stories in this collection, “The Line” is the one that most echoes the voice and charm of Gentleman in Moscow, perhaps because of the setting, but also because the protagonist, while very different, carries himself with the same easy likability and dignity as Count Rostov.

My favorite story, “The Ballad of Timothy Touchett,” is about a young writer who gets a job at a rare bookstore as he searches for motivation and inspiration. Noting the facility with which Timothy had previously copied F. Scott Fitzgerald’s signature, the owner of the bookshop (delightfully named Mr. Pennybrook) innocently asks him if he might sign a copy of John dos Passos’s The 42nd Parallel “on Mr. Dos Passos’s behalf” for a sick friend who has a signed first edition of every other work by that author. Young Timothy isn’t totally stupid, but he does it anyway and. . . you can see where this might lead. What I most enjoyed about this story is the way Towles speaks of the forged signatures as art. When Pennybrook admires Timothy’s execution of Hemingway’s signature, he notes “Your slanted i is no less than the lance of the picador projecting from the back of a bull.”

Economics is a frequent theme in these tales, from the brief study of life under communism in “The Line,” to the manipulation of family for economic gain that occurs in “The Didomenico Fragment,” to Timothy’s selling out of dreams for a little extra cash (“Suffice it to say that at the fork in the road, offer a young man an extra fifty dollars a week in exchange for a modest adjustment to his dreams, and you will have him by the throat.”). Relationships, particularly the dynamics of marriage, are explored: In “I Will Survive,” a once-cheated on woman feels betrayed and suspicious when her second husband lies about where he’s going every Saturday; in “Hasta Luego,” a cancelled flight leads a stranger get pulled unwillingly into a woman’s desperate attempts to save her husband from his drinking problem (the husband in this case being as affable from a distance as John Candy in Planes, Trains, and Automobiles); in “The Bootlegger,” a husband and wife have different perspectives when their date nights are interrupted by an old man illegally recording concerts at Carnegie Hall.

These stories mostly hit the right notes. “The Bootlegger” seems to be leaning toward saccharine when we learn more about the old man making the recordings, but the real punch comes on the last page, when the wife shares her evolving experience with music–something she can only share with the reader, not with her husband. The only story without a touch of sadness is “The Didomenico Fragment,” and for that reason it’s the least effective story in the book.

Eve in Hollywood

Eve in Hollywood follows Eve, a character from Rules of Civility (which isn’t necessary to read first–I hadn’t) from the moment she decides to stay on a train bound for Chicago and extend her ticket to Los Angeles. It’s a mostly light but entertaining novella told through multiple points of view and taking place during the Golden Age of Hollywood. Charlie, a retired police detectives that Eve meets on the train, describes Los Angeles to her: “He told her what she already knew–about the rise of the studios and the matinee idols, the mansions and the grand hotels. But he told her about the other Los Angles too. The one that had emerged from the dust right alongside the glamorous one and had grown just as fast, if not faster. The Los Angeles of the gangsters and grifters and ladies of the night. That city within the city that had its own diners and cable cars, its own chapels and banks–that had its own fashioning of failure and folly, and of grace and integrity too.”

In this Los Angeles, Eve meets and befriends Olivia de Havilland (you might expect it to be the other way around, but Eve is a tough cookie and Olivia, at this point, is an inexperienced starlet under the aegis of the studio system). During one of their evenings out, a photographer snaps a mildly compromising photo of Olivia, and Eve manages to retrieve it. This so impresses David O. Selznick and company that they offer her a job “watching out” for Olivia (they first frame it is a favor, but like I said, Eve’s a tough cookie and she ain’t dumb). When the actress receives a blackmail note with nude photos of herself, she immediately turns to Eve.

This novella has a noir feel about it–there’s blackmail, seedy locations, and a retired cop. As I said, it’s light, but it also addresses the very relevant topic of privacy. In 1930s Hollywood, nude photos would ruin Olivia’s reputation as she’s about to take on the role of Melanie Hamilton–the biggest of her young career. One character ponders an array of nude photos of various actresses, “Fanning the pictures out, Litsky shook his head in wonder. Before him were women whose reputations were as white as their skin. Which is to say as white as snow. White as ivory. White as a pitcher of cream. It was a cash-register ringing symphony in that color without hue.” These women were marketed to the public as pure, perfect, and angelic. A hint of scandal would cost the studios too much. And once again we’re back to economics. The flexible morality of the city when it comes to money is summed up: “For anything that was done in Los Angeles illegally could be done in Los Angeles with the full backing of the law, as long as it was set up in the right way. Because the law, like everyone else in this city, was on the payroll.”

The studio system is also a target. At one point, the story alludes to the real-life incident when Jack Warner refused to lend de Havilland out to Selznick to do Gone with the Wind, prompting the desperate actress to appeal to Warner’s wife. Warner eventually gets back at de Havilland by casting Bette Davis in the starring role of The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex opposite Errol Flynn, with de Havilland relegated to a lady in waiting. I’m not sure whether the studio head’s motivations for that casting were confirmed in real life, but from what I know about Jack Warner, I don’t doubt it.

Attitudes toward women are also a key theme. The photographer Litsky gave me the creeps early on by his habit of referring to Oliva as “Dehavvy” (ick), but he becomes absolutely repellant when he learns about the nude photos. In his mind, a woman whom he was unable to exploit the first time facing public exposure and humiliation is justice. When he learns that Eve (the woman who bested him) is involved, he’s downright gleeful. This character particularly exudes a need to keep women “in their place.”

I really enjoyed this collection; as I said, it should have been two books: The short stories about New York in one, and the novella about Los Angeles in the other. Collections work best when the individual stories build on each other, which is accomplished by the six short stories. Eve in Hollywood, on the other hand, is best enjoyed on its own.