Cbr16bingo Dun dun

Cbr16bingo Dun dun

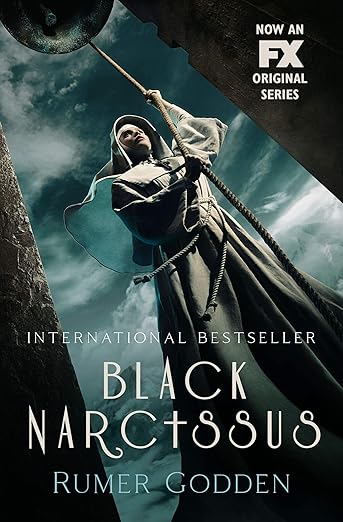

This is my first foray into Rumer Godden’s works. Black Narcissus was published in 1939 and was turned into a movie in 1947. Apparently it was made into a 3-part miniseries on FX a few years back, too. I was aware that Godden’s work often touched on matters of religion and spirituality but I was not prepared for the suspense and foreboding that haunt the pages of this story. It reminded me a bit of Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca — an innocent young woman or women, in this case nuns, find themselves invited into an unknown and inhospitable environment, and we know that some kind of tragedy is looming ahead. I was also reminded of Joan Lindsay’s 1960 novel Picnic at Hanging Rock for its sense of the enormous power that nature can have on one’s psyche. I was completely enrapt by this story about the clash of cultures, religions and personalities.

Black Narcissus is the story of a group of missionary Anglo-Catholic nuns whose Mother Superior sends them to establish a school and hospital in a remote area near the Himalayas. An order of brothers had attempted to do the same and abruptly left the mission without explanation. The General who controls the land wants very much to try to establish a worthwhile mission in the palace there, partly as an act of benevolence but also to try to erase the unsavory history of the palace that he inherited from his ancestors. General Toda is mostly absent from the mission/palace at Mopu, but his agent Mr. Dean is always there. From the outset, both Dean and the housekeeper Ayah make it clear that the nuns should not be there, that this is a wasted effort. Dean predicts that they will not last until the rains. For young sister Clodagh, the youngest sister superior in the convent’s history, this is a challenge. The clash of these personalities — Dean and Clodagh — is a central part of the story. Dean is an Englishman who has “gone native”; the locals accept him as one of their own, but he is often drunk and a womanizer, too. Dean is the consummate sinner, and yet his challenges to Clodagh and the convent show a more mature spirituality, one that often brings Clodagh up short. Clodagh is a very talented woman, intelligent and organized, but, as the Mother Superior points out to her, she can be somewhat smug, filled with her own self-importance. The nuns who join Clodagh are Sister Blanche, aka Sister Honey, a lovely young woman who adores children; Sister Philippa, who oversees gardening and laundry; Sister Briony, a very capable and sensible woman who oversees medical services; and Sister Ruth. Ruth is in some ways like Clodagh — young and very smart. Her job is to run educational services at the mission. Yet Ruth is also temperamental and jealous of Clodagh. In the words of Mother Superior, Ruth “wants importance” and she hopes that Clodagh can spare some of her own. Between Ruth and Dean, the authority of Clodagh and the mission will face some formidable challenges.

Yet these personality clashes are not the only obstacle to the mission’s success. Certainly, there is a cultural difference between the European sisters and the people of this Himalayan village. Initially, the nuns think of these people as “other,” but with time, some of them begin to overcome their racism a bit to admit that “they’re just like us.” And yet, they are not exactly like the sisters. From the General’s point of view, they are ungovernable, and yet they have established an order of their own. They don’t see the need for a school or clinic and will only go when the General bribes them to do so. It is clear that those who have tried to “educate” these villagers in the past have had no lasting impact on them. Colonizers come and go, the people remain the same. Dean’s views of the native people are complicated; on one hand, he respects their way of life and sees no need for outsiders to come in and impose new ways on them. On the other, he is there to oversee the business (tea production) that enriches the General and that the villagers would not bother with otherwise. Dean begrudgingly helps the sisters with the mission, overseeing plumbing and building issues, and the sisters would have failed rapidly without his help. Yet, they do not listen closely to some of his advice regarding their interactions with the native people, and it will come back to haunt them.

The other factor that influences the sisters and their mission is the environment itself. Despite their best efforts, the buildings are always cold and drafty; the winds are fierce. But it is not just the temperature that has impact. The mountain itself, Kanchenjunga, seems to exert some sort of force over everyone. The views from the mission are breathtaking, but there is also something about this environment that seems to influence the psyche. Clodagh begins to think about her youth and the young man she once loved. All of the nuns seem to lose track of time and to be easily distracted. The mountain seems to take whatever latent tendencies the nuns have and magnify them. For Clodagh there is also the sense that perhaps they should not be here, that there is something wrong with what they are doing. Even Mother Superior and the priest who oversees the region seem to be warning Clodagh that this endeavor might not end well and that she needs to be able to admit that.

All of these factors — personality, culture and environment — are clearly stacked up against the nuns from the earliest pages of the book, and as the story progresses, the sense of foreboding increases. We can see the cracks in the convent community and perhaps guess some of what will happen, but that does not make the final act of Black Narcissus less powerful or shocking. This novel was a pretty quick read but the amount of detail and character development made me go back and reread large sections of it. Rumer Godden is a masterful storyteller and while there may be some cultural insensitivity in some of the story (worth discussing in a group) I would recommend this novel to anyone interested in matters of religion, spirituality and colonialism.