Cbr16bingo Vintage

Cbr16bingo Vintage

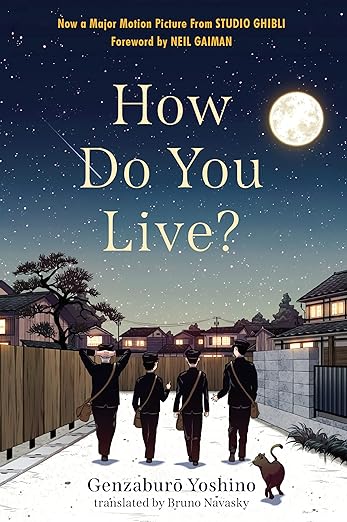

This book, published in Japan in 1937, is a classic of Japanese literature and served as the inspiration for the Hayao Miyazaki film “The Boy and The Heron”. This translation by Bruno Navasky is the first time How Do You Live? has been translated into English, and it features an introduction by Neil Gaiman. Genzaburo Yoshino was born in 1899 and earned a degree in philosophy from Tokyo Imperial University. The Japan of his youth was becoming increasingly militaristic and even had “thought police” that targeted communists and socialists in particular. Yoshino, a socialist, went to jail for 18 months. Later, a friend got him job editing books for young readers. Yoshino and his friend decided to write an ethics book for children, emphasizing the need for freedom and exposure to other cultures as prerequisites for progress. Rather than writing a textbook, they decided to make it a story, How Do You Live? This is a short, beautifully written story about an adolescent boy nicknamed Copper; his friends; their school; and Copper’s uncle. Chapters focus on incidents from Copper’s life followed by a chapters that are his uncle’s reflections on Copper’s actions and thoughts, as well as his hopes for Copper’s future.

Copper and his friends represent a cross section of Japanese society. Copper’s father was a successful banker but has died. He and his mother have had to move and downsize, but they are still financially stable, and Copper’s uncle has stepped in as a kind of surrogate father. Copper respects and confides in his uncle, and his uncle in turn begins to keep a diary with messages for Copper to consider as he grows older. The two engage in a wide range of conversations, from the inter-connectedness of countries and people, to history, politics and economics, and also ethical and moral questions. These matters arise often in respect to things that happen in Copper’s everyday life as a student. Copper has three close friends. Mizutani has been his friend since they were little; his family is quite wealthy and his older sister will challenge the boys both intellectually and physically. Kitami, like Copper, is kind of small but he has a strong character. Once Kitami makes up his mind, he does not change easily but he also will stand for what is right even when it causes him pain. Finally there is Uragawa, a boy who is shy, awkward and poor. As a result, he is the object of much bullying from his classmates, but Copper discovers that there is much more to Uragawa than meets the eye and develops great respect for this boy and his working class family.

The ethical and moral issues addressed in this book are set out through clear stories that will resonate with most readers because they are the kinds of situations that we have all faced at one time or another: bullies, socio-economic differences and prejudices attached to them, recognizing one’s responsibilities toward others and trying to figure out where one fits in the larger world. One of the big issues that Copper has to grapple with is regret and remorse. Reading about the incident that causes this will be familiar to many; I think almost all readers can put themselves in Copper’s shoes when he behaves in a way that he is later ashamed of. The chapters in which Copper must come to terms with his own shortcomings are the most powerful in the book, and the way his mother and uncle help him navigate this provides a wonderful example for parents and caregivers to follow as well.

The overall point of How Do You Live? is to get the reader to think about what it means to live a good life and what the point of a good life should be. Yoshino wrote this book at a time when authoritarianism, xenophobia and rabid nationalism were on the rise in Japan, Germany, Italy and elsewhere. For Yoshino, the only way forward was (and is) to remember our commonalities and inter-connection with one another and to remember that all real progress comes from working together. This would be a lovely book to gift to a tween or older, maybe as a graduation gift, as it deals with many important topics (art, friendship, bullies, politics, ethics). Yet while this book was written with children in mind, it is a worthwhile book for adults to read as well, especially in our current world of growing repression, xenophobia and intolerance. It’s a reminder of how we ought to live and think, and how we should be helping children grow up to be responsible, moral, ethical individuals.