The thrill that comes from reading a classic of any particular genre is you get to see the early formation of that particular class of fiction. That can also be a problem, as the object of inspiration often leads to greater literary feats that can sometimes make the early attempts feel underwhelming. That’s sort of how I felt about the first three books in the Earthsea series, though I definitely got more engaged as I made my way through the trio.

The thrill that comes from reading a classic of any particular genre is you get to see the early formation of that particular class of fiction. That can also be a problem, as the object of inspiration often leads to greater literary feats that can sometimes make the early attempts feel underwhelming. That’s sort of how I felt about the first three books in the Earthsea series, though I definitely got more engaged as I made my way through the trio.

A Wizard of Earthsea introduces a young boy, nicknamed Sparrowhawk, who grows up on the island of Gont in the Earthsea Archipelago. After displaying a proficiency for magic, Sparrowhawk is taken in by a wizard named Ogion for the purpose of training him to become a great wizard himself. Under Ogion’s tutelage, Sparrowhawk is given his “true” name, Ged. Ged learns from Ogion, but he becomes frustrated with the wizard’s slow, methodical ways and decides to go to the wizard school on Roke Island to speed up his training.

At the school, Ged makes friends and an “enemy” and acts like a bratty schoolboy, as kids away from home for the first time sometimes do. When he tries to show off by performing a spell that is beyond his power, things go very wrong–he releases a terrible “shadow” that terrifies him and scars his face. Ged then spends the rest of the novel running from the shadow and simultaneously trying to figure out whether it’s possible to defeat it.

What makes A Wizard of Earthsea different from the fantasy that came before it is that it chronicles the making of a wizard. Ged isn’t a wise old man with a beard (much as we love you, Gandalf!) but a young boy who is too insecure, too easily offended, and too proud to approach his education with wisdom and patience. He makes critical mistakes because he is young and flawed. He releases a terrible power because he fails to take to heart the lessons from his education. As one of the school’s teachers explains to Ged, “To change this rock into a jewel, you must change its true name. And to do that, my son, even to so small a scrap of the world, is to change the world. . . . But you must not change one thing, one pebble, one grain of sand, until you know what good and evil will follow on that act. The world is in balance, in Equilibrium. A wizard’s power of Changing and of Summoning can shake the balance of the world. It is dangerous, that power.” The great responsibility that comes with being a wizard is one of the lessons that Ged needs to learn in order to defeat the shadow.

The Tomb of Atuan is also what we might call a “coming of age” story, but this time about a girl named Tenar, who lives on the island of Atuan. Tenar is believed to be the reincarnation of Atuan’s last High Priestess, and if that isn’t enough to cause serious developmental issues in a pre-teen girl, I don’t know what is. She was taken from her family at the age of 5 and renamed “Arha,” which means “the eaten one.” (Yikes! Her entire identity and history have been gobbled up!) Her childhood is lonely, to say the least–she has a eunuch named Manan and one young priestess friend, but the rest of her time is spent with stern teachers who train her to be High Priestess of the Tombs.

When Arha is 14, her world is rocked by an intruder breaking into the Tombs. She traps him in the labyrinth under the tombs and, as High Priestess, she should rightfully have him killed, even if it’s just by starving him to death in the labyrinth. Instead, she starts to talk to the intruder, who turns out to be. . . Ged! A slightly older, somewhat wiser Ged has come to Atuan in search of the lost half of a ring (the ring of Erreth-Akbe, which was mentioned briefly in A Wizard of Earthsea). The ring is a talisman that Ged needs to help bring peace to Earthsea.

What will Arha do? Will she kill Ged? Will she be victorious in the power struggle with the Priestess Kossil? Will she reclaim her identity and become Tenar again? What makes this novel special for early fantasy is it explores ethical questions and religious differences–Tenar and Ged come from warring cultures. There is no one “hero” in this novel; Tenar has Ged in her power and can easily have him killed, which he acknowledges. She explores her options from both moral and practical perspectives.

Obviously, Ged survives, or he wouldn’t be able to return for. . .

The Farthest Shore. In this third novel, Ged is an Archmage of the ripe old age of 40 (or thereabouts)! Whew, he has really grown into the long beard and pointy wizard hat at this point. In this novel, Earthsea has been stricken with a strange malignancy, in which magic seems to be losing its power. Ged decides to go in search of the cause, bringing with him a young prince named Arren. The prince has some of the pride/arrogance we saw in Ged in the first novel, asking “How would a goatherd become an archmage?” when he learns of Ged’s background. Ged and Arren push out to sea in Ged’s boat Lookfar (another callback from the first novel), and as they visit different towns and communities, they discover the sickness is widespread. In one town, they learn that a wizard has been promising people that they will be able to live after death; in another, people who celebrate through song are suddenly struck dumb and can’t remember the words. When the pair encounter dragons who have lost power of speech, you know things have become serious!

While I enjoyed the pacing and action of this novel the most of the three, I had one significant complaint in that the bad guy is revealed to be someone whom Ged had defeated previously, but to whom the reader had never been introduced. I found myself flipping back through the first novel to see if I had forgotten a minor character. In my mind, introducing a brand new villain with a “So, we meet again, Old Nemesis” tone is cheating. I suppose it could have been done effectively, but I was annoyed in the moment.

Overall, these novels have strengths and weaknesses, but they are definitely milestones of the genre. If you are a fantasy geek, you will undoubtedly be thrilled by the extensive maps that Ursula K. Le Guin includes. Cartographers will delight in the map of Earthsea with its many island clusters, although I enjoyed the Labyrinth of the Tombs of Atuan even more.

Many reviews have commented on the absence of strong female characters, particularly in A Wizard of Earthsea, and that complaint is more than fair. Le Guin herself comments on this in the introduction to this volume: “Why was I, a woman, writing almost entirely about what men did?” She answers herself that, as an avid reader when she was young, she learned from the books she read and loved, which were almost entirely focused on men. But then–and this is one of the many reasons I love Le Guin–she calls herself out on that excuse: “Oh, well, now was that true? Hadn’t I read Jane Austen? Emily Brontë? Charlotte Brontë? Elizabeth Gaskell? George Eliott? Virginia Woolf? Other, long-silenced voices of women writing about both women and men were being brought back into print, into life. And my contemporary women writers were showing me the way. It was high time I learned to write of and from my own body, my own gender, in my own voice.” These types of observations about her own work are what compel me to read every foreword and afterword that Le Guin writes. In this case, it makes me eager to read the remaining books in the series, in hopes that she adjusted her course.

Another point that often gets missed (because, in her own words, Le Guin was kind of “sneaky” about it) was that her hero Ged, and most of the other characters, are not stereotypically white. She notes that, in 1967, many readers would not be ready to accept a brown-skinned hero. Yet, Ged’s people, the Archipelagans, are described as copper- or brown-skinned, even though most readers didn’t notice the distinction. (She notes that some publishers insisted on putting a light-skinned hero on the book jacket, and regrets that, at the time, she didn’t have enough clout to change that. Some covers she approved of more than others.)

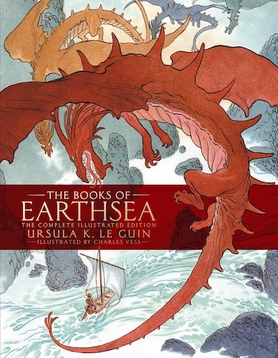

I’m not promising you a rollicking crazy time with these three books, but I haven’t read a single thing by Le Guin yet that wasn’t worth my time, and I stand by that. I see these as important milestones in the development of fantasy, and the author’s bucking of early trends by focusing on a young, flawed, non-white wizard nudged the genre forward. In addition, I highly recommend the 2018 Sea Press collection (see picture at the top of this review) for the wonderful illustrations by Charles Vess. This is a volume you can dive into and feel like you are in another world.