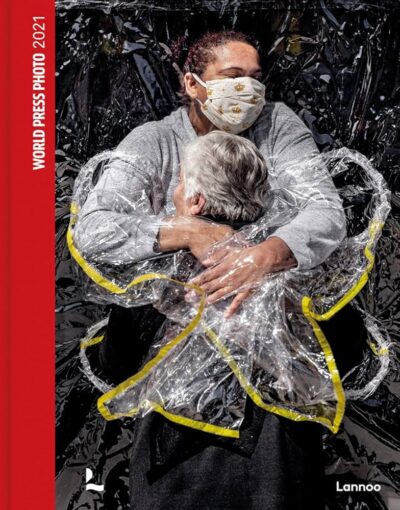

World Press Photo 2021 was an interesting one for me because it made me think a lot about what I like about photojournalism and why this particular volume wasn’t clicking for me. There’s a bit in the book where they talk about how the field has switched to focusing more on the photographer having a particular personal vision and trying to capture a photo that sums up some sort of larger issue or event, versus earlier photographers who were trying to capture an exciting photo in the moment. However, the Photo of the Year contest still seems to choose more of the kinds of photos that resonate for me, so I think it’s less that the whole field has changed and more that there is a split between different areas of focus within it. World Press Photo is a Dutch organization with an international lens, while Photo of the Year is an American organization (albeit with a lot of international photographers included). To me, the photos in World Press Photo 2021 feel more like they are working hard to make an ideological point or to win an argument, while Photo of the Year still has the vibe of attempting to do straight documentary photography. While the World Press photos are on a very high level, there were not many that really stuck with me or jarred me, whereas when I read old Best of Photojournalism books (which were done by Photo of the Year) the photos seem more uniformly striking and thought provoking. Don’t get me wrong, there are definitely a lot of great photos here, and I especially liked Jeremy Lempin’s photo of a woman with cancer and a horse, and Luis Tato’s story on a locust swarm in Kenya. The book as a whole just didn’t blow me away.

World Press Photo 2021 was an interesting one for me because it made me think a lot about what I like about photojournalism and why this particular volume wasn’t clicking for me. There’s a bit in the book where they talk about how the field has switched to focusing more on the photographer having a particular personal vision and trying to capture a photo that sums up some sort of larger issue or event, versus earlier photographers who were trying to capture an exciting photo in the moment. However, the Photo of the Year contest still seems to choose more of the kinds of photos that resonate for me, so I think it’s less that the whole field has changed and more that there is a split between different areas of focus within it. World Press Photo is a Dutch organization with an international lens, while Photo of the Year is an American organization (albeit with a lot of international photographers included). To me, the photos in World Press Photo 2021 feel more like they are working hard to make an ideological point or to win an argument, while Photo of the Year still has the vibe of attempting to do straight documentary photography. While the World Press photos are on a very high level, there were not many that really stuck with me or jarred me, whereas when I read old Best of Photojournalism books (which were done by Photo of the Year) the photos seem more uniformly striking and thought provoking. Don’t get me wrong, there are definitely a lot of great photos here, and I especially liked Jeremy Lempin’s photo of a woman with cancer and a horse, and Luis Tato’s story on a locust swarm in Kenya. The book as a whole just didn’t blow me away.

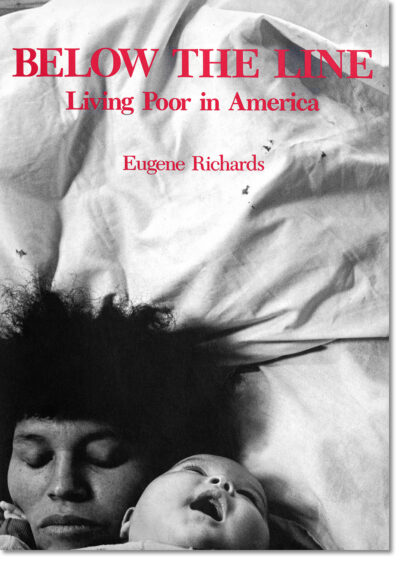

In line with the sort of documentary photojournalism that I enjoy, Below the Line: Living Poor in America was extremely enjoyable for me and reminded me of one of my favorite books of all time, American Pictures. The book is told in a monologue format, with the narrative of the person next to photographs of their life. Eugene Richards is an amazing photographer and captures heartbreaking moments while retaining an eye for human dignity even under extremely adverse conditions. Porta Lee Davis’s story of having to pick three hundred pounds of cotton a day at age eight while surviving on almost no food (a few cherry tomatoes she scrounged out of the fields and a little flour she scraped out of the side of a barrel) for weeks was so inhumane and infuriating, but this is the sort of conditions people lived in within recent memory, and still live in today. The book is from 1987, so only three years before I was born, and I’m sure you can find equivalent stories easily if you went out with a similar assignment. I wish that books like this were more widespread, because the fact that it shows you story after story made it sink in for me than just an article online. It’s the continuous presentation and the knowledge that millions of people are going through similar poverty and deprivation. This is a great book and definitely recommended for anyone interested in social issues and seeing how much or how little the country has changed.

In line with the sort of documentary photojournalism that I enjoy, Below the Line: Living Poor in America was extremely enjoyable for me and reminded me of one of my favorite books of all time, American Pictures. The book is told in a monologue format, with the narrative of the person next to photographs of their life. Eugene Richards is an amazing photographer and captures heartbreaking moments while retaining an eye for human dignity even under extremely adverse conditions. Porta Lee Davis’s story of having to pick three hundred pounds of cotton a day at age eight while surviving on almost no food (a few cherry tomatoes she scrounged out of the fields and a little flour she scraped out of the side of a barrel) for weeks was so inhumane and infuriating, but this is the sort of conditions people lived in within recent memory, and still live in today. The book is from 1987, so only three years before I was born, and I’m sure you can find equivalent stories easily if you went out with a similar assignment. I wish that books like this were more widespread, because the fact that it shows you story after story made it sink in for me than just an article online. It’s the continuous presentation and the knowledge that millions of people are going through similar poverty and deprivation. This is a great book and definitely recommended for anyone interested in social issues and seeing how much or how little the country has changed.