My father has always insisted that people only say “the book was better than the movie” because they read the book first. In his opinion, if you read the book first, then you spend the movie missing all the characters and scenes they’ve had to cut for time. However, if you’d watched the movie first, then while you reading the book you’d find yourself annoyed by all the superfluous material that’s clearly not needed since it didn’t make the film version.

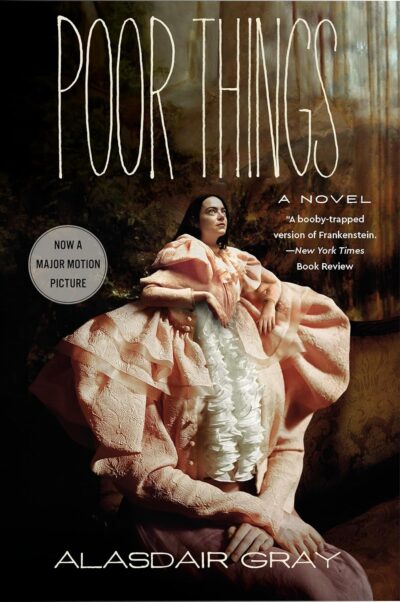

Whether my father’s theory holds up in all or most cases, it certainly explains my reaction to Alasdair Gray’s novel Poor Things, which was of course adapted into a very successful film last year. The movie, of course, starred Emma Stone as Bella Baxter, a woman saved from death by an unconventional surgery which replaced her own brain with that of the baby she was carrying at the time of her death. Bella essentially becomes an adult-sized baby, re-learning everything about the world as she rapidly grows back into her body. The film mainly focuses on Bella’s hunger for ideas and sex, which she pursues with equal vigor. Bella’s curiosity and guilelessness make her ripe for being taken advantage of, but the force of her personality carries her through the worst of it.

The novel is structured very differently than the film. Alasdair Gray presents the story as a series of competing narratives. The bulk of the story is split between a supposed memoir by Bella’s eventual husband, Dr. Archibald McCandless (played by Ramy Youssef in the movie) and a response written by Bella herself. Dr. McCandless’s memoir contains most of the film’s plot: Bella’s attempted suicide, rescue by Godwin Baxter (Willem Defoe), world tour exploring her sexuality with Duncan Wedderburn (Mark Ruffalo), and eventual marriage.

In Bella’s response, she casts doubts on the veracity of her husband’s memoir, claiming the whole thing to be a fiction intended to make him look good. She claims to have never only pretended to be an amnesiac to escape her abusive first husband, and that she only married McCandless out of a combination of expedience and pity.

Gray positions himself as an academic feuding with a colleague over which of these narratives to believe. He presents apparent historical research in support of both positions, claiming to let the reader decide which side of the story to believe.

Gray has a remarkable gift for mimicry. Both McCandless’s and Bella’s narratives read as though they were really written by people alive in the 19th century. However, I have to say that I found the presentation of the novel became tedious to me after a while. Whereas the film told one compelling story with a wholly unique character at its center, Gray’s novel tells too many stories from too many perspectives and becomes completely centerless. Eventually, I lost interest in the little games Gray was playing, and just wanted a story I could lock into.

But like I said, had I encountered the novel first, who knows? Perhaps I would have found the film limited and missed all the other stuff Gray included.