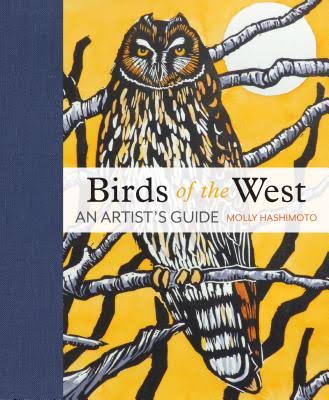

Over the past twenty years, I’ve become a fairly avid birder. More recently, I’ve begun to re-cultivate the interest in drawing I first developed as a young teen. During the pandemic, I started watching online tutorials about nature journaling and, more specifically, drawing birds. Molly Hashimoto’s Birds of the West, an Artist’s Guide, is a wonderful source of inspiration. It’s a combination field guide, art book, and how-to manual.

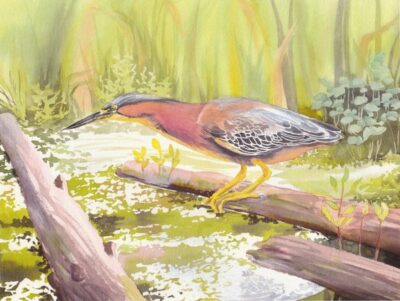

Hashimoto specializes in block prints and watercolors, though she also shares some etchings and images she has done in gouache. While I’ve so far stuck with the more basic media of colored pencils and ink (and honestly, the odds of me ever trying my hand at block printing are infinitesimal), the book also offers quiet wisdom about art and nature, and the reasons people create art. Reverence for the subject is one reason; understanding that feeling is another. She quotes a letter Georgia O’Keeffe wrote to Sherwood Anderson and then goes on to explain, “Georgia O’Keeffe believed that we want to make art of things that have moved us deeply, even if we don’t know exactly why or understand the meaning of what we feel. It is only by recording it, writing about it, or making art about it that it becomes clearer to us what it all means and why it is so important to us.”

She also talks about the benefits of drawing from live observations (the most difficult aspect of nature journaling, in my opinion). She tells the story of visiting the Seattle Aquarium and drawing a tufted puffin while watching scores of youngsters marveling at all the animals. She observes, “The only way a person over the age of five can react to nature as a child does, with an innocent lack of expectation and genuine excitement, is to approach living creatures as if you’ve never seen them before, or heard of them, or read about them, or learned their names. One way to do that is to try to draw them. Then you aren’t thinking, ‘puffin, plover, oystercatcher.’ All you’re doing is experiencing the colors, the shapes, and the movements.”

I’ve noticed that when I’m sketching, even if it’s from a still photo, I’m drawn into a much deeper appreciation of the details. I’m not just seeing “gray bird, patches of white on the wings,” etc. I’m seeing how the feathers overlap, how thick the wing bars are, how yellow the eye is. I’m taking in more details in a way that makes me not only appreciate the bird more, but also makes me a better birder.

If you’re interested in the artist’s techniques, she also provides guidance for how she creates some of her art. I’m not terribly familiar with block printing, so it was interesting to read about how many blocks she has to make, depending on the number of colors. She provides a list of resources at the end of the book, including recommended tools and other materials (one nitpick: an index would be helpful).

This is an excellent resource for someone who loves art and loves nature. It includes basic information about some of the most common birds of Western North America, with the birds organized by habitat (for example Backyard & City, Wetlands & Ponds, Alpine & Tundra). The addition of poetry and personal observations take it to a more personal level than a standard field guide or “how-to.” Birds of the West makes a nice addition to a library, either as a coffee-table book or as a source of motivation before you start your next nature-art project.