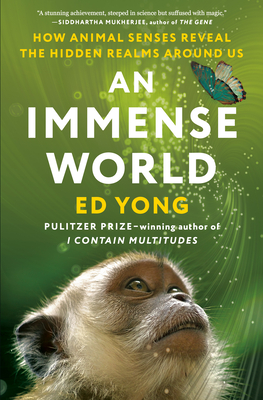

Ed Yong takes us through the vast world of animal senses with understandable explanations of complicated science and a startling humor that made me laugh out loud, in public, many times. From misquoting Jane Austen to lamenting his poor choices in clothing, Yong adds delightful levity to a complex and fascinating subject.

Ed Yong takes us through the vast world of animal senses with understandable explanations of complicated science and a startling humor that made me laugh out loud, in public, many times. From misquoting Jane Austen to lamenting his poor choices in clothing, Yong adds delightful levity to a complex and fascinating subject.

When we think about how animals see the world around them, we are already biasing our analysis based on humanity’s strongest sense, that of sight. How an animal “sees” the world is better described as how they interact with it, because depending on the animal, they use wildly different senses in order to navigate their environment. Yong introduces the reader to the concept of “umwelt”, a term that (loosely) means the biological foundations that underlie human and animal communication. For example, certain species of tree frogs have better success mating if they add a “chuck” sound to their call that the females find attractive, and it was the females’ preference that spurred the evolutionary change in the call. But the males are reluctant to “chuck” because their predators’ hearing has evolved to better hear at that frequency, and males that “chuck” often find themselves someone else’s dinner. The environment impacts the species, and changes how they interact with the world.

Unlike Yong, I’m doing a poor job of explaining the concept, but believe me that it is fascinating. Yong walks us through a variety of senses and the species that most rely on them. The book is laid out by sense; sight and then into color, smell, hearing, taste, touch and vibration, heat, pain, and then into the stranger senses of electric fields and magnetic ones. It is fascinating (yes, I used the word again), and stretches the imagination to try to place yourself into the umwelten of these various species. Some are easier than others; I can imagine a more vibrant world filled with the rurples, yurples, and grurples that are the ultra colors most other animals besides humans can view. Others are more difficult; can I really imagine having multiple arms that literally have minds of their own, like octopuses do? But Yong has a way of explaining that makes you just about able to grasp it, even briefly, even dimly.

Yong finishes with a strong call to action to preserve the dark of night and the silence that so many animals rely upon. Noise and light pollution are hugely impactful in many ways, and are changing species’ behavior and environments so rapidly that they are struggling to acclimate. We humans must work to restore the sensory environment that we modified. The good news is, it is almost certainly something we can (fairly) easily fix; we just have to find the collective will to do it.