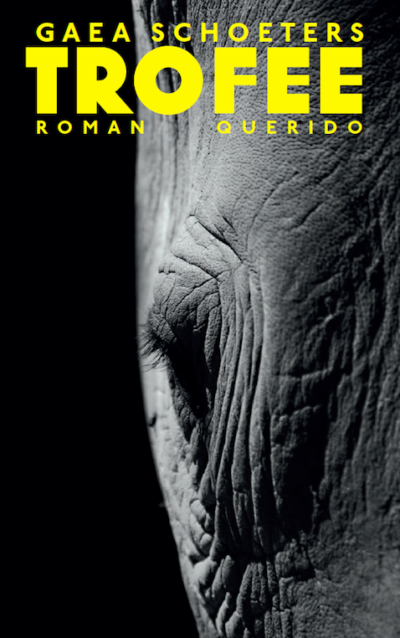

Hunter White has one passion in life: hunting. And he’s about to achieve the pinnacle of his favourite hobby: he has purchased a license to shoot a rhinoceros, thereby completing the Big Five, something he has dreamed of since his grandfather took him hunting as a young boy. He considers himself a skilled hunter, someone who respects the craft. No cheesy poses on top of a lion for him, no semi-automatic weapons, no faff. Just him, and the animal. And several local guides, of course, and a stay in a five star resort with air conditioning, a swimming pool, and a couple of G&Ts by the fire, but still – Hunter respects nature, respects the craft. But soon, things go awry, and the hunt turns into a direction that both exceeds Hunter’s wildest dreams – and his nightmares.

Hunter White has one passion in life: hunting. And he’s about to achieve the pinnacle of his favourite hobby: he has purchased a license to shoot a rhinoceros, thereby completing the Big Five, something he has dreamed of since his grandfather took him hunting as a young boy. He considers himself a skilled hunter, someone who respects the craft. No cheesy poses on top of a lion for him, no semi-automatic weapons, no faff. Just him, and the animal. And several local guides, of course, and a stay in a five star resort with air conditioning, a swimming pool, and a couple of G&Ts by the fire, but still – Hunter respects nature, respects the craft. But soon, things go awry, and the hunt turns into a direction that both exceeds Hunter’s wildest dreams – and his nightmares.

Trofee (Trophy) is a bit of an odd book. It’s hardly subtle in the points that it makes, from the main character’s name to the direction in which the plot soon turns. Hunter, as a main character, is hard to relate to: his identity quite literally is just that, a Hunter. He makes his money as an amoral stock trader, staying just inside the bounds of the law to milk his clientele for all they are worth; the money seems to be poured straight back into hunting. There is a nameless woman at home who is concerned for his welfare, for whom he collects trophies, though he could not care less about those himself. Hunter’s entire life seems to revolve around the moment he pulls the trigger on an animal he has not yet killed before.

I think you can guess the direction in which this goes.

It’s a well written novel; it’s overly descriptive in places, and then it tends to drag on a bit, but Schoeters is excellent at building tension. But it also veers into cliché territory in the way Hunter talks about himself, as some sort of Tarzan if Tarzan had been a Wall Street day trader. The way Hunter sees it, he’s doing the country a favour; he spends hundreds of thousands of dollars on a license that will pay for roads, schools, hospitals in this poor-as-dirt, unnamed county. And really, he’s helping them from an ecological point of view too: the rhino he aims to shoot is old, will no longer breed and contributes nothing to the conservation efforts made to protect the species. He considers himself “an explorer or a pioneer; the realisation of claiming this land, simply by entering it. The same desire that drives men to virgins.” All those Westerners with their ideas of conservation? Well, they don’t understand how it works. His perspective is the one Kipling wrote about, updated for the new millennium: let the people with the money take care of things, because the natives can’t be trusted with it.

He’s also the sort of person who regards the locals as an animal species; he respects their ability to track animals, but at the same time he regards them as just another species of fauna. He has deliberately learned nothing about their habits and cultures: he believes in “selective knowledge, specialisation.” At one point he compares a group of villagers to “a pack of hyenas circling the car… Mzungu, mzungu, it hums all around him, the only African word he knows because it pertains to himself.”

This mentality, of course, is the point of the novel, and from the onset we know it’ll not end well regardless of what happens during the hunt, but I was rather astonished by the author’s choice to have the novel take place in a nameless country. Too many western authors regard Africa as a monolith rather than a diverse continent with hundreds, if not thousands, of languages, cultures and religions and by not acknowledging that, the author falls, or steps, into the same trap. Perhaps that’s the point: we see Africa through Hunter’s eyes and he certainly doesn’t care. And yet, the ‘otherness’ of African culture isn’t exactly romanticised, but rather weaponised: Hunter keeps himself outside of the local customs as much as the locals keep him out. There’s an element of horror in this novel that I’m not sure I appreciated.

Ultimately, I find it difficult to rate this book. It is undoubtedly a skilfully written book and at times, it’s taut and thrilling. However, the way local African people, customs and cultures are described are off-putting, and the novel has an acerbic, gloomy tone that may have been appropriate, even deliberate, but it also comes across as gleefully vindictive. A good read, yes, but an acerbic one too.

As far as I know, this novel has not been translated into English.