Words are powerful. They too can be the agents of what is new, of what is conceivable and can be thought and let loose upon the world.

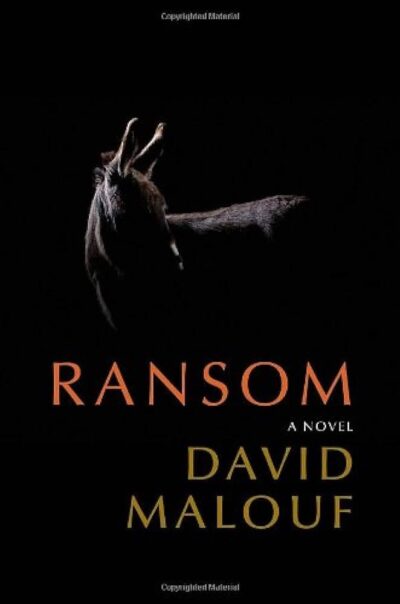

It’s me, an absolute sucker for classical retellings. There’s the obvious vogue of them going on right now, between Jennifer Saint and Claire North and Madeline Miller and Pat Barker &etc, but there’s also plenty of preceding ones, and when I learned (altogether too late) about David Malouf’s Ransom, I had to read it to see if it was another one worth recommending to my students.

Ransom is a retelling of the Iliad, but one with a precise, narrow focus: most of the actual plot that Malouf borrows is from Book 24, the last part of the text, when Priam steals into the Greek camp to attempt to ransom back the desecrated body of his son Hector from the Greek warrior Achilles. It’s not a moment that lacks for attention: perhaps one of the most famous rewritings of this scene is Michael Longley’s “Ceasefire,” which links this episode with the 1994 ceasefire between the IRA and the British, signaling the beginning of the end of the Troubles. And that moment is indeed the climax of Ransom as well (not a spoiler, it’s a 2500+ year old text!); the twists, turns, and surprises are what comes along the way, instead.

borrows is from Book 24, the last part of the text, when Priam steals into the Greek camp to attempt to ransom back the desecrated body of his son Hector from the Greek warrior Achilles. It’s not a moment that lacks for attention: perhaps one of the most famous rewritings of this scene is Michael Longley’s “Ceasefire,” which links this episode with the 1994 ceasefire between the IRA and the British, signaling the beginning of the end of the Troubles. And that moment is indeed the climax of Ransom as well (not a spoiler, it’s a 2500+ year old text!); the twists, turns, and surprises are what comes along the way, instead.

Achilles and Priam are your two main characters here, but Malouf expands one other character significantly to give us a central triad: Somax, a carter, who is hired to transport Priam and the ransom in question to the Greek camp. Somax is just an ordinary man: widowed, with only one of his children still alive, and devoted to his granddaughter, who that day is home suffering from a fever. The most transformative parts of the narrative are the journey with him and Priam: this is perhaps the first time Priam has engaged at length with one of his common citizens, and Somax, with his decency, courtesy, and his own burden of griefs, is precisely the companion Priam needs in this moment when he is undertaking something that perhaps no one has ever done before. A moment I have always wrestled with is Priam’s claim to Achilles that he is doing what no man has ever done before when he gets down on his knees to supplicate for return of Hector’s body: supplications are nothing new, ransoms for bodies are mentioned elsewhere in the text. But Malouf examines the way in which Priam steps out of his ceremonial role, and in this moment also reminds the great man-killing, city-sacking Achilles of their dual humanity, of what binds them together:

We are mortals, not gods. We die. Death is our nature. Without that fee paid in advance, the world does not come to us. That is the hard bargain life makes with us — with all of us, every one — and the condition we share. And for that reason, if no other, we should have pity for one another’s losses. For the sorrows that must come sooner or later to each one of us, in a world we enter only on mortal terms.

Achilles, in his awful grief, must hear these words; his desecration of Hector’s corpse is after all just the external manifestation of his internal horror that his best friend has died (no, Malouf doesn’t really engage with the idea that they were lovers, though he doesn’t take the possibility off the table either). Malouf makes stronger here the idea that death is a horror in all kinds of ways to this man who has killed so many: it is his own mortality that separated him from his beloved, deathless mother, mortality that robbed him of Patroclus, and his own death that inches ever closer now that he has killed Hector.

And Malouf does, thankfully, keep the divine element firmly within the story: Priam has visions that are divinely-sent, Achilles is definitely the son of a goddess, Hermes pops up to serve the same role he does in the original tale, Hector’s body is miraculously intact despite being dragged behind a chariot day after day. The marvelous is so necessary here, and Malouf employs it deftly, with its wonder heightened when seen through the eyes of Somax, who after all is a mortal who would otherwise have no contact with gods, unlike the great men he rubs shoulders with here. He and his much beloved donkey, Beauty, are the audience surrogates whose gentleness and wonder heightens the grandeur of everything else.

It’s a short read, too: I whipped through it in maybe two hours. But it lingers in the mind, and it is a bit different from, though sitting comfortably alongside, the many other classical retellings we’ve gotten lately.