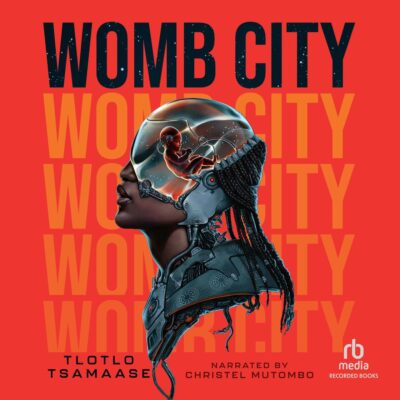

Tootle Tsamaase’s Womb City showed up on several lists for most anticipated 2024 science fiction, and the Afrofuturist dystopia angle of it sounded exciting and different. And clearly also a work with a feminist eye towards women’s autonomy, but providing a different angle than standard issue Western white feminism. I had really high hopes for this one; science fiction is such a potent genre for examining political questions and this looked so fresh and distinctive.

The plot summary was also compelling: Nelah lives in a futuristic Botswana where crime has been reduced to all-time lows, but only through oppressive surveillance measures. People can also upload their consciousness into new bodies and thus live new lives, but if they are uploaded into a formerly “criminal” body, they are microchipped and surveilled; also, once uploaded in a new body, one loses all memory of their past life and relations, and their “new” relatives (because the body comes with its own history) may or may not accept one. Nelah, a successful architect, is in this situation: her body is criminal, her new family seems to hold her at arms’ length, and her husband, a high-ranking official in the police force, is controlling. She has a baby incubating in an external womb, and financial anxiety about this dominates her life; it’s understandable why she has a lover on the side, and on a reckless night with him, she has a hit-and-run accident where she kills a young woman. Nelah and her lover hide the body, but the vengeful ghost comes after her. Can Nelah appease the ghost, atone for her sins, and uncover the dark secrets at the heart of her society? Time to find out!

Womb City definitely is distinctive, but it didn’t quite live up to my hopes. It’s a debut novel, and sometimes a debut comes out like a fully-formed gem, and sometimes you can see the seams and rough edges; this is the latter. Tsamaase doesn’t fully seem to trust her reader to grasp her political message about misogyny and women’s oppression, so she hammers it home in the bluntest terms at every possible turn, sometimes killing the narrative momentum when she has Nelah, her protagonist, stop in the middle of whatever she’s doing to think long and furiously about the unfairness of the world. It is unfair, but the reader can grasp that without such bludgeoning. There’s also a tendency towards repetition; Nelah will have the same complaint, either spoken or aloud, again and again at different points in the narrative. Again, this feels like a tremendous lack of trust in the reader to grasp the themes, which are themselves not all that subtle. The characterization also feels inconsistent; given that Nelah is paranoid about the microchip that surveils her, and constantly fretful about the daughter whose existence depends upon her making money and passing behavioral checks, it seems almost unbelievable that she would go out for a late-night drive while drunk and high out of her mind (especially since it turns out these cars do have self-driving modes).

Tsamaase’s prose can be occasionally a bit florid, but when reined in a little it’s vivid and heady; there is a lot of potential that this novel demonstrates. A stronger edit would have yielded a stronger book, trimming repetition and building some of the bigger plot reveals more organically into the text. The creativity here is remarkable; it just needs a stronger structure to trust on, and a little more faith in readers who actually do want to go where Tsamaase is taking them.

I listened to an audiobook of this, and Christabel Mutombo was an excellent narrator.

(Also, content note: this one is kinda gory! not extraneously so, but brace for some significant gore and a bit of body horror in high-tension moments.)