I have a very thoughtful husband who keeps his eyes and ears open for books he thinks I’ll enjoy. Often, these turn out to be winners, and I can see why he thought Unmentionable would be right up my alley. I love Victorian literature and history, having read and enjoyed Judith Flanders’s massive The Victorian City last year. I also like humor and have been known to engage in snarky commentary now and then. Unmentionable, then, seems like a safe bet for me.

I have a very thoughtful husband who keeps his eyes and ears open for books he thinks I’ll enjoy. Often, these turn out to be winners, and I can see why he thought Unmentionable would be right up my alley. I love Victorian literature and history, having read and enjoyed Judith Flanders’s massive The Victorian City last year. I also like humor and have been known to engage in snarky commentary now and then. Unmentionable, then, seems like a safe bet for me.

What I’m about to say may be controversial: There is such a thing as too much snark. Hear me out. I think of snark as the nutmeg of communication: A little bit adds depth and flavor; a little more can even make you high; go overboard, and you’re suddenly vomiting and being dragged to the ER by your college roommate. To make the experience pleasant for everyone, you want a light hand with the nutmeg/snark.

Obviously this is a humor book, so it may seem unfair that I’m complaining about too many jokes, but this book truly became so annoying I wasn’t sure I could finish it. It opens by addressing the reader (you) as a young woman who wants to visit the Victorian era because of all the romantic novels she has read growing up. The author’s purpose, then, is to disillusion the reader by highlighting all the unfair, annoying, and downright horrible shit that a woman in that era had to tolerate. Fair enough, and a perfectly reasonable setup. However, a couple of things really, really irritated me. First, the author’s tone is one of addressing a young, idiot child. I don’t think she goes two pages without addressing the reader as dearie, sweetheart, darling, and–worst of all–lambkin. Second, you would think that this would be a perfect channel for highlighting how far women’s rights have come since the Victorian era and how far we still have to go. I would say that, in a 300-page book, I paused maybe three times and thought, “Yeah, it’s interesting how much that resonates with women’s rights today.”

It’s not that the author doesn’t have enough material. Between menstruation, birth control, owning property, and Victorian men following an entirely different set of rules, there is plenty to comment upon. But the author does just that–comments and moves on to the next joke without any real depth or analysis.

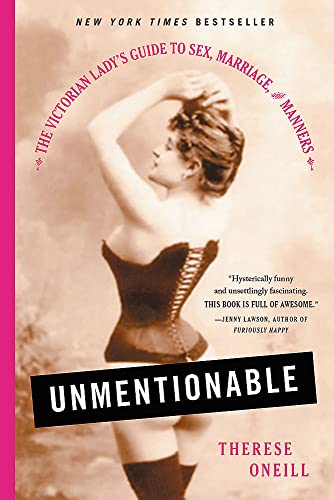

I’ve come to the conclusion that this book should have been a blog. Author Therese Oneill is a humorist/historian who has written for Mental Floss, Jezebel, and The Atlantic, and I can see how her style would be suited to short bites of humor–something I can dip into and enjoy in small doses.

I wanted to like this book. Alas, Unmentionable, I’m just not into you.