Do you remember the movie A Time to Kill?

This movie is almost 30 years old, which I think pretty much excludes it from the need for spoiler alerts, but in case you haven’t seen it, spoilers ahead: in this movie, Samuel L. Jackson’s daughter is brutally attacked by a crew of racist white men, and because he knows he won’t get any justice for his daughter from the legal system he takes his shotgun and openly murders the culprits (in a truly dramatic way, at the courthouse I believe). He hires Matthew McConaughey to represent him in his trial, and at one point he tells him that there’s a reason he hired this white-boy lawyer – not because he’s different from the jurors but precisely because he’s one of them. And Matthew McConaughey knows what he needs to do – he walks into court and tells the jury the story of what happened to Samuel L. Jackson’s daughter, in brutal detail – and finally he asks the mostly white jury to imagine that this little girl is white. And with this gut punch directed squarely at the limits of empathy, the jury delivers a not-guilty verdict.

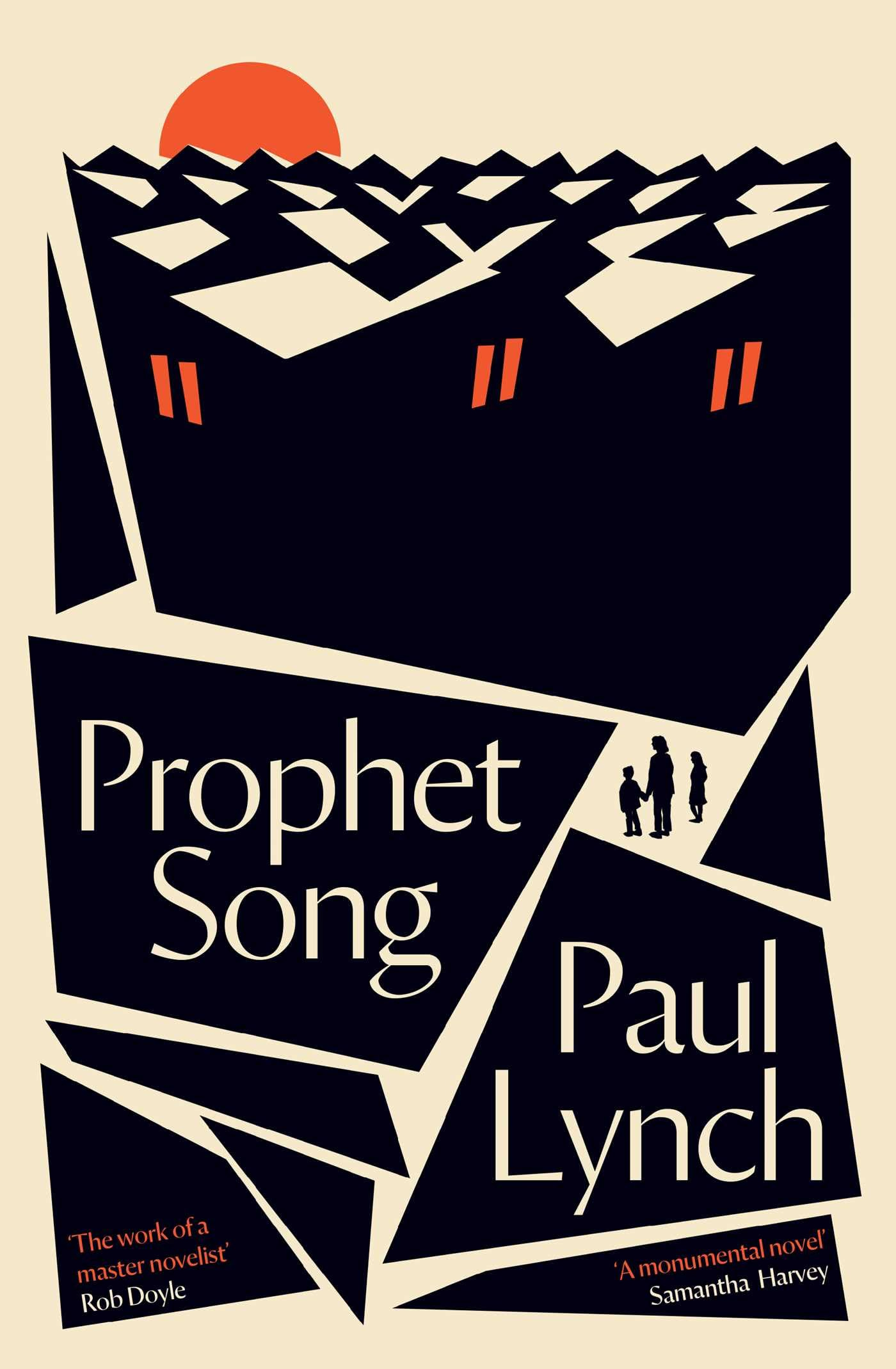

Prophet Song – a Booker Prize award winner – is similar in concept to that moment. Paul Lynch takes the very real suffering of people all over the world, most of whom are not white, and he puts them into the context of a white family (in this case a family in Ireland), and I get the sense that this is meant to activate those same empathy sensors. Lots of people loved this novel, but I can’t really say that I’m one of them.

This novel gave me anxiety from the beginning. A family is simply living their life in Ireland – the father, Larry Stack, represents a teachers union; the mother, Eilish, is a microbiologist, and together they have four children who range in age from 16 to about 6 months. Recently a totalitarian party has assumed power, and they are infiltrating the government at a rapidly increasing pace. Over the course of 9 chapters and just over 300 pages, we are treated to Eilish’s increasingly more maddening thoughts as we watch her family like frogs in boiling water. A sense of doom is present from the first pages, where Larry struggles with deciding whether or not to attend a planned protest with his union. From there, the tension escalates as the reality of the situation slowly presents itself to Eilish. This is real – their family is in a war zone, and she must decide when and how to protect her family.

Eilish’s choices were limited and none seemed very good – and yet page after page of living in her darkened mind, without any ability to impact her inertia, made me sympathize with her daughter Molly who eventually seems to simply recede into herself when she cannot urge her mother into action. Each page was filled with long, tense sentences – no paragraph breaks, or quotation marks – deepening the claustrophobic feeling. It was quite effective at making me feel the frustrated terror this family faced – but to what end? Yes, this book was effective in creating an emotional experience – but no, I did not really enjoy it.

I see the value of a novel like this – one that supports the development of empathy, especially in a time when everywhere we look people are living in conditions just like this and it’s heartbreaking and terrifying. It’s uncomfortably clear that we could be facing another attempt to Make America A Dictatorship (maybe for just a day? can I do just a LITTLE bit of dictator stuff?) Again. Even acknowledging the importance of the topic, I can’t say I liked this novel. As the depth of the emotional pain reaches it’s low point, rather than feeling a surge of empathy, I felt instead a surge of frustration at being emotionally manipulated.