There will be spoilers from She Who Became the Sun here, be warned.

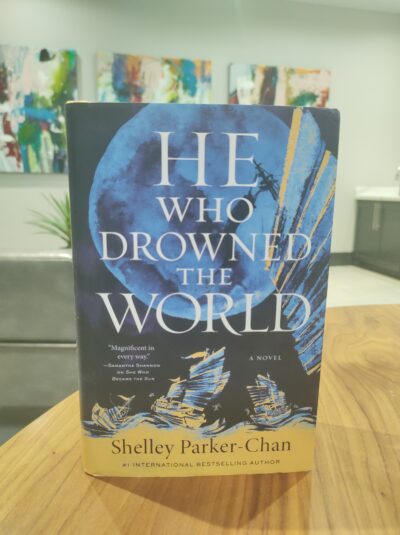

He Who Drowned the World was one of my more anticipated reads this year, and Emmalita was so very kind and sent me a copy. So, I owe it to squeeze this review in before the year’s end.

She Who Became the Sun was an absolutely fantastic book that really put Shelly Parker-Chan on the map. But it was also a book that was eager to give you a gut punch. Or two. Or an absolute flurry that left you on the ground clutching your solar plexus. Parker-Chan was not kind.

In She Who Became the Sun, Zhu Chongba stole her brother’s destined greatness and, rather than remaining a nameless daughter, became first a monk and then the leader of the Han rebellion against the Mongols. On the opposing side, acting as an almost second protagonist, was the Mongol eunuch, General Ouyang. Who was a man of many, many internal conflicts—including whether people even perceived him as a man. And as I progressed through She Who Became the Sun, despite my growing attachment to Zhu, I couldn’t help but think she was inching closer and closer to being the villain.

He Who Drowned the World picks up with both characters not long after we left them in She Who Became the Sun. But, in a move that made me very happy, we also get more of Wang Baoxiang, the then-Prince of Henan’s scheming adopted brother. He’s a bastard, but he was my favourite bastard, so I’m more than happy to see more of him. Although he is less than happy to be where he is—or who he is. We also delve into the viewpoint of the much-put-upon Madam Zhang, who could crush Zhu if she’s not careful.

Now, with the duology being heavily influenced by historical events (something I came into this book knowing), I sort of know what the resolution would be for Zhu, at least. But for the others, their eventual fates were less clear. And what I couldn’t guess was how destructive the choices of every character could be. Every single character is contending with the terrible situations they have found themselves in. How they react boils down to how blinked each of them is or how consumed they are by their own search for power. I had previously thought Zhu’s pursuit of greatness very one-eyed and narrow, but Madam Zhang’s obsession with social status, Ouyang’s hot white hate, and Baoxiang’s self-loathing-driven determination may give her a run for her money. Of the four, Zhu’s ambition might be the least selfish, so she doesn’t quite veer as hard into the villain-protagonist role that I thought she might have at the end of She Who Became the Sun.

One huge theme that carries over from the first book is the power of sex and the weight of gender expectations. But what we really see here in the sequel is a much more heavy weaponisation of said expectations. I really don’t have a more articulate way of explaining it, but more than one POV indulges in it. And one particular individual allows the crushing weight of these internalised expectations to utterly consume them. And it just hurts to read about.

Another thing of note, while the touch of magic was so light in the first book that I thought it barely brushed fantasy, this is no longer the case in He Who Drowned the World. The importance of the Mandate of Heaven is emphasised the closer each character gets to the throne. It does read more like fantasy this time around, and it increases the degree of detachment from the historical events that the overreaching story is based on, which I actually prefer.

Otherwise, I really can’t talk too much more about the book without getting into the plot, which I want to leave mostly untouched. But it is a brutal, but otherwise very fitting conclusion to She Who Became the Sun.

Gutting, but amazing