Bingo (In order): Guide, Relationships, Nostalgia, Europe, Adulthood

Passport: England

When Alan Garner’s Treacle Walker was shortlisted for the 2022 Booker Prize I was surprised, not because I don’t think he’s a brilliant writer worthy of a major literary award, but because awards like this don’t seem to take fantasy seriously, despite the depth of the ideas and the beauty of the prose, and I hadn’t realised that this author I loved in my childhood was still alive and still writing.

Treacle Walker is not your typical fantasy tome, at a slight 131 pages, but now well into his 80s, Garner has taken the themes that recur in his earlier work and distilled them down to their essence where “every why has its wherefore”.

Treacle Walker, the Ragbone Man offers a boy a trade and reality shifts on its axis. Or was it always so, a whirligig that doesn’t move even as fresh water flows through it, always there, the same but never the same? As the cuckoo calls, an ancient body stirs in his bog, and Stonehenge Kit the Ancient Brit chases a Wicked Wizard through a chain of mirrors back into the pages of a comic, Treacle Walker comes again, and again, to guide Joe to where he has always been.

Next up I went back to what had been the favourite Garner of my childhood, The Owl Service. The edition I read this time came with an introduction by Phillip Pullman that places it in its context as a modern classic that made it “both possible and necessary to take children’s literature seriously” and highlights Garner’s use of “sharp… tense and brilliantly economical” dialogue.

First published in 1967, this book is surprisingly in tune with the zeitgeist and feminist retellings of myth, even though the surface layer of the book centres Gwyn and his difficult class position as an ambitious Welsh teen whose mother is the housekeeper for a well-to-do blended English family, much more than Alison.

The magic at the heart of the story, trapped in the valley like water in a reservoir, is a power leashed and twisted into a shape not of its own choosing, forcing its story to be told and retold and its energy to be spent by three who “must bear that mind, leash it, yet set it free, through us, in us, so that no one else may suffer”.

Garner takes an ancient Welsh tale of a woman crafted from flowers, given to a man to be his wife, and then punished for preferring another, and subverts the traditional reading of a woman’s treachery. “She wants to be flowers, but you make her owls. You must not complain, then, if she goes hunting.” Can Gwyn, Alison and Roger find a way to break the cycle?

The Weirdstone of Brisingamen is Garner’s first novel published in 1960, and the first I read. It is a simpler but engaging story of two children sent to stay in the West Country while their mother is in hospital who stumble into a magical battle. One one side is a wizard who stands guard over one hundred and forty knights in silver armour waiting in enchanted slumber to wake in the hour of England’s greatest peril, with his brother and the Morrigan on the other.

While the stakes are high, the focus is tight and small. The children’s magical quest takes them no further than a few miles across the countryside, but they travel deep down into the roots of the folklore that Garner learned in his own childhood. One section from this novel has haunted me for decades, as the children and two dwarven companions flee from supernatural enemies through a narrow tunnel deep in a cave system. Colin and Susan’s pursuit by supernatural creatures and having to literally fight for their lives held a fraction of the terror Colin faced with “hundreds of feet of rock above and the miles of rocks below …. wedged into a nine-inch gap between”, then forcing himself under the water of a flooded tunnel of unknown length after deciding “better a quick road to forgetfulness than a lingering one.”

The 1963 sequel, The Moon of Gomrath, continued Colin and Susan’s adventures on Alderley Edge. The plot is more complex than its precursor, including possession by an evil force, a quest to restore a lost spirit, a war to defend the elven lands, the return of the Morrigan, and accidental summoning of the Wild Hunt.

I found the broader scope and increased cast of characters less engaging. The narrative felt overstuffed with so many Celtic, Anglo-Saxon and Norse legends referenced with little explanation and no clear overarching narrative. There was definitely plenty of action, but less emotional connection, at least for me.

I still found plenty to enjoy though, both as a child and now. A highlight for me was the house that was only in the earthly realm while the moon shone on it, and discussion of the tension between the High Magic of wizards, and the more chaotic and feminine Old Magic.

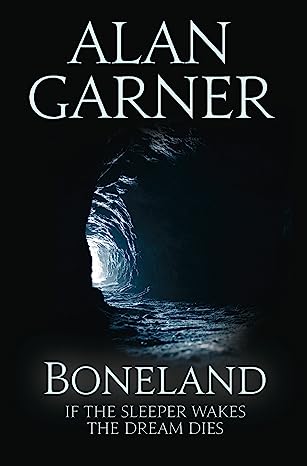

In hindsight, the greatest value of the Moon of Gomrath was in setting up the masterful Boneland. This sequel was a long time coming, not published until 2012, and is most definitely not for children. This is the book that put Garner on the Booker radar, and should itself have been shortlisted or even the winner, as impossible as the idea of a major literary award for a sequel to a 50 year old children’s book might seem.

Boneland is the story of the deeply buried damage done to Colin by the events of the first two books, and of his deep connection to Alderley, or to reality itself, not that there appears to be any meaningful difference.

Adult Colin is an odd, introverted astrophysicist using the telescopes of the Jodrell Bank Observatory to search the stars for a sister that he can’t remember. She belongs to the time before his memories start, behind the stark line drawn between the two sundered pieces of his life he can remember nothing and every detail of.

In another deep past time, an Ice Age shaman carves the rocks of Alderley Edge, to keep the world on its axis.

Colin’s therapist, who might be a crow, or a witch, a mirror, or the moon, helps him to remember the deeper truth so that everything can continue.